All About De Stijl: The Avant-Garde Movement that Pushed Modern Art Towards Abstraction

Summary

Reflection Questions

Journal Prompt

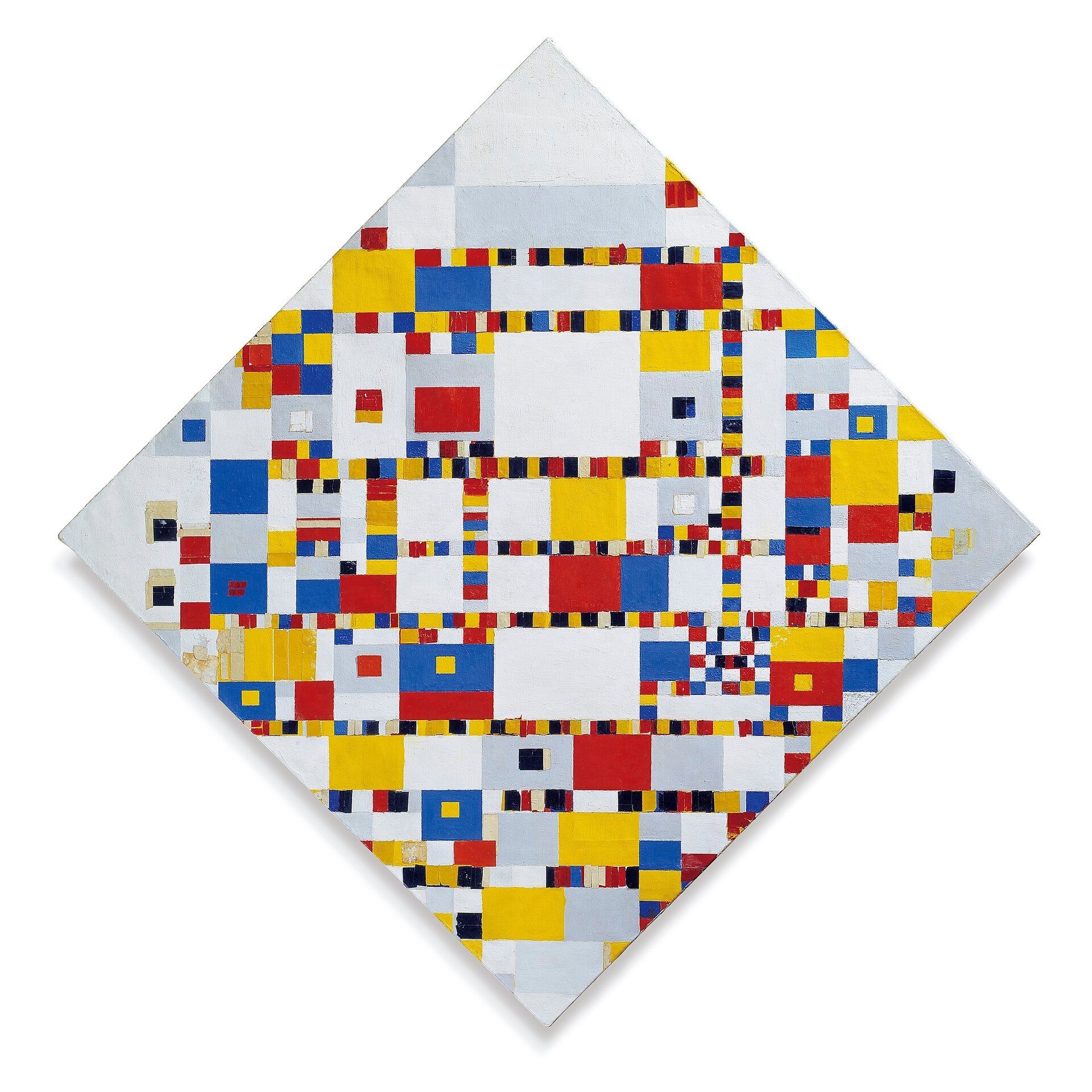

De Stijl—an avant-garde artistic movement originating in the Netherlands circa 1917—embodied a confluence of geometric abstraction and primary colors that epitomized its aesthetic rigor and ideological purity. Born from the tumult of World War I as a visual and intellectual manifesto against the chaos of the time, it sought to transcend the disorder through art that espoused universality and fundamental simplicity. With leading figures such as Piet Mondrian and Theo van Doesburg at the helm, De Stijl—which literally translates to “The Style”—imposed a strict discipline of vertical and horizontal lines and eschewed any form of decoration that did not serve structural purposes. Its impact—still resonant in the realm of modern art—is seen not only in the works it directly influenced but also in its foundational principles that continue to underpin the aesthetic and conceptual approaches of minimalist and contemporary abstract art and design. The significance of De Stijl lies in its radical reconfiguration of artistic norms and its enduring quest for harmony through reduction—which has left an indelible mark on the trajectory of modernist endeavors.

Origins of the De Stijl Movement

The origins of De Stijl can be traced back to a period of profound upheaval. The devastation of World War I prompted a widespread yearning for change and a new societal order, which significantly influenced the cultural and philosophical zeitgeist. This backdrop of reconstruction and re-evaluation provided fertile ground for the inception of De Stijl.

Reaction to the Horrors of World War I

The movement emerged as a direct response to the war’s brutality—embodying a utopian ideal of balance and harmony in the face of Europe’s physical and moral wreckage. Artists and intellectuals sought a visual language that reflected a break from the past—a fresh start that would not only heal but propose a universal solution to the disjointed world.

Introduction of Neoplasticism

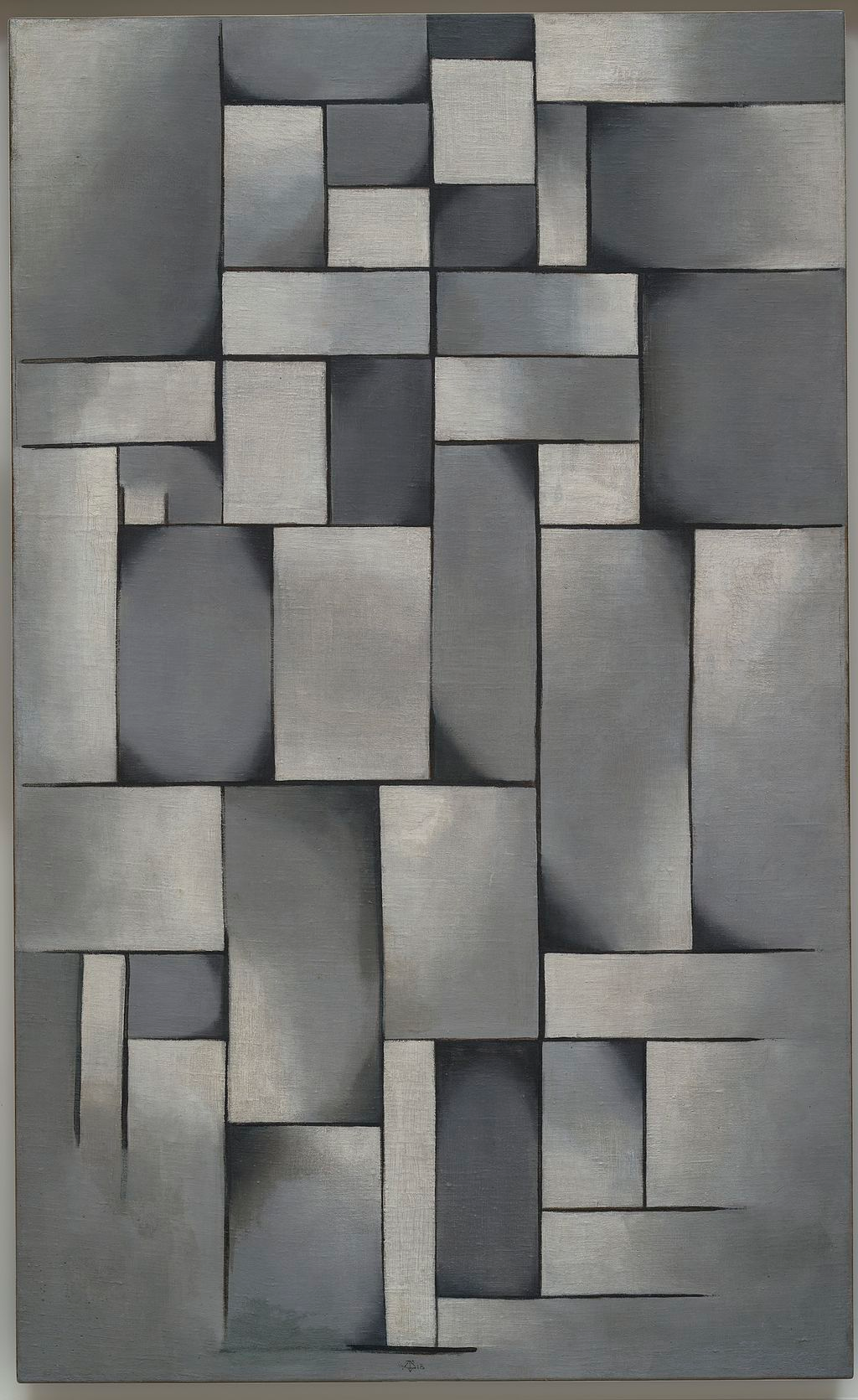

Central to De Stijl’s philosophy was the concept of Neoplasticism—introduced by Piet Mondrian. It was a form of pure abstraction that reduced art to its basic elements: straight lines, right angles, and primary colors supplemented by black, white, and grays.

This reduction was not merely aesthetic but also philosophical, as Mondrian’s Neoplasticism was deeply rooted in his belief in a spiritual and aesthetic order aligning with the universe’s natural laws. This harmony was what De Stijl aimed to manifest in the physical world—thereby healing the rifts opened by the war.

Theosophy and Spiritual Harmony

Theosophy—with its emphasis on spiritual harmony and unity—further influenced De Stijl’s artists, embedding within the movement a mystical dimension that transcended mere artistic reform. Theosophical teachings promulgated an understanding of an underlying spiritual order that could be reflected in the material world—an idea that resonated deeply with the movement’s pioneers who were seeking a universal language of form and color that could be understood by all—irrespective of cultural or geographical boundaries.

Piet Mondrian and Theo van Doesburg’s Role in the De Stijl Art Movement

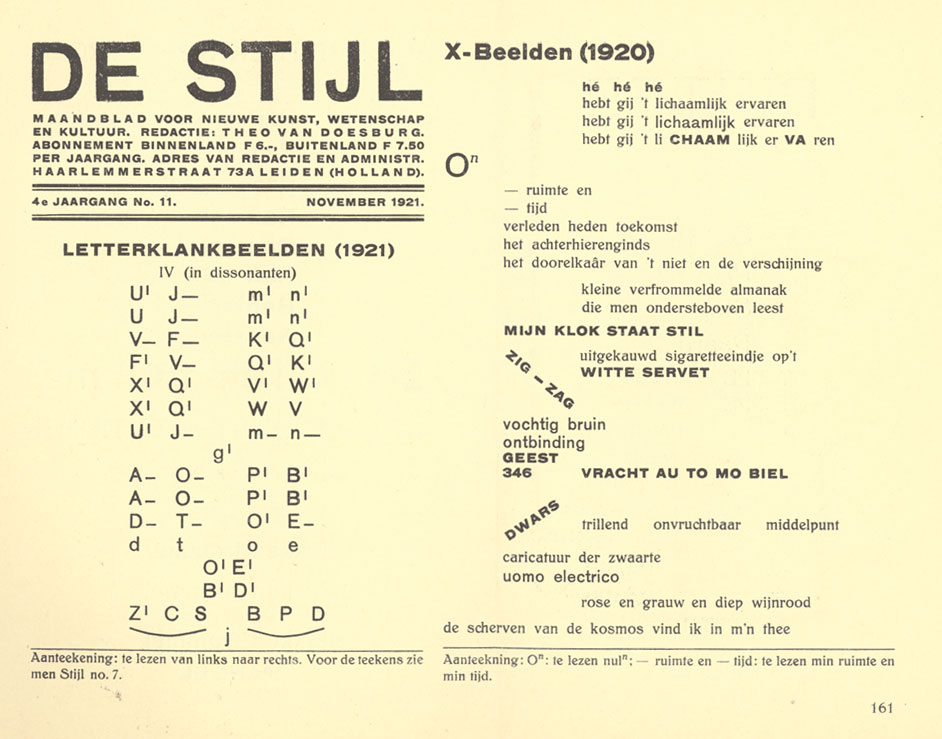

Piet Mondrian and Theo van Doesburg were pivotal in founding De Stijl. Both artists were searching for a new art that did away with the individualism and naturalism of the 19th century. In 1917, they—along with several like-minded artists—gave shape to their ideas through the launch of a publication aptly named “De Stijl”—which would serve as the movement’s mouthpiece.

The De Stijl manifesto they published therein laid down the fundamental principles of the movement—emphasizing a radical abstraction that aimed to achieve visual harmony through the balance of opposites. The manifesto did not merely describe their artistic intentions but was a call to a broader application of their ideas—advocating for their integration into all aspects of life and design, with the goal of creating an environment reflective of their new ideological paradigm.

Fuel your creative fire & be a part of a supportive community that values how you love to live.

subscribe to our newsletter

*please check your Spam folder for the latest DesignDash Magazine issue immediately after subscription

Characteristics of De Stijl Art

The aesthetic principles of De Stijl were characterized by rigorous simplicity and abstraction. The movement stripped away the vestiges of representational art—distilling visual expression to its purest elements.

Abstraction and Simplification

It embraced an extreme form of simplification where every line, color, and plane had a deliberate function, both in terms of form and meaning. This was a conscious choice to move away from the artifice of perspective and the illusion of three-dimensional space, towards the creation of a new, two-dimensional pictorial art vocabulary.

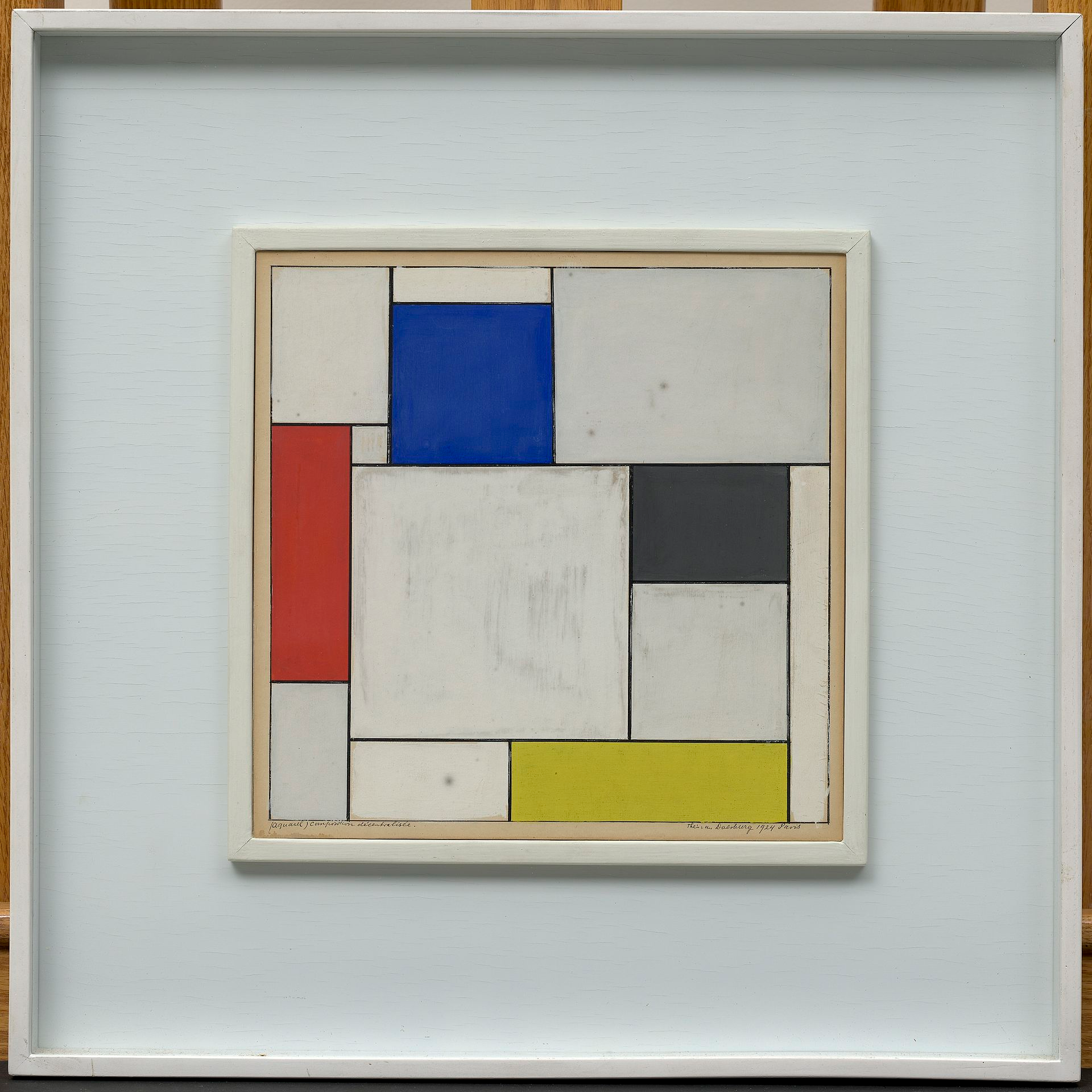

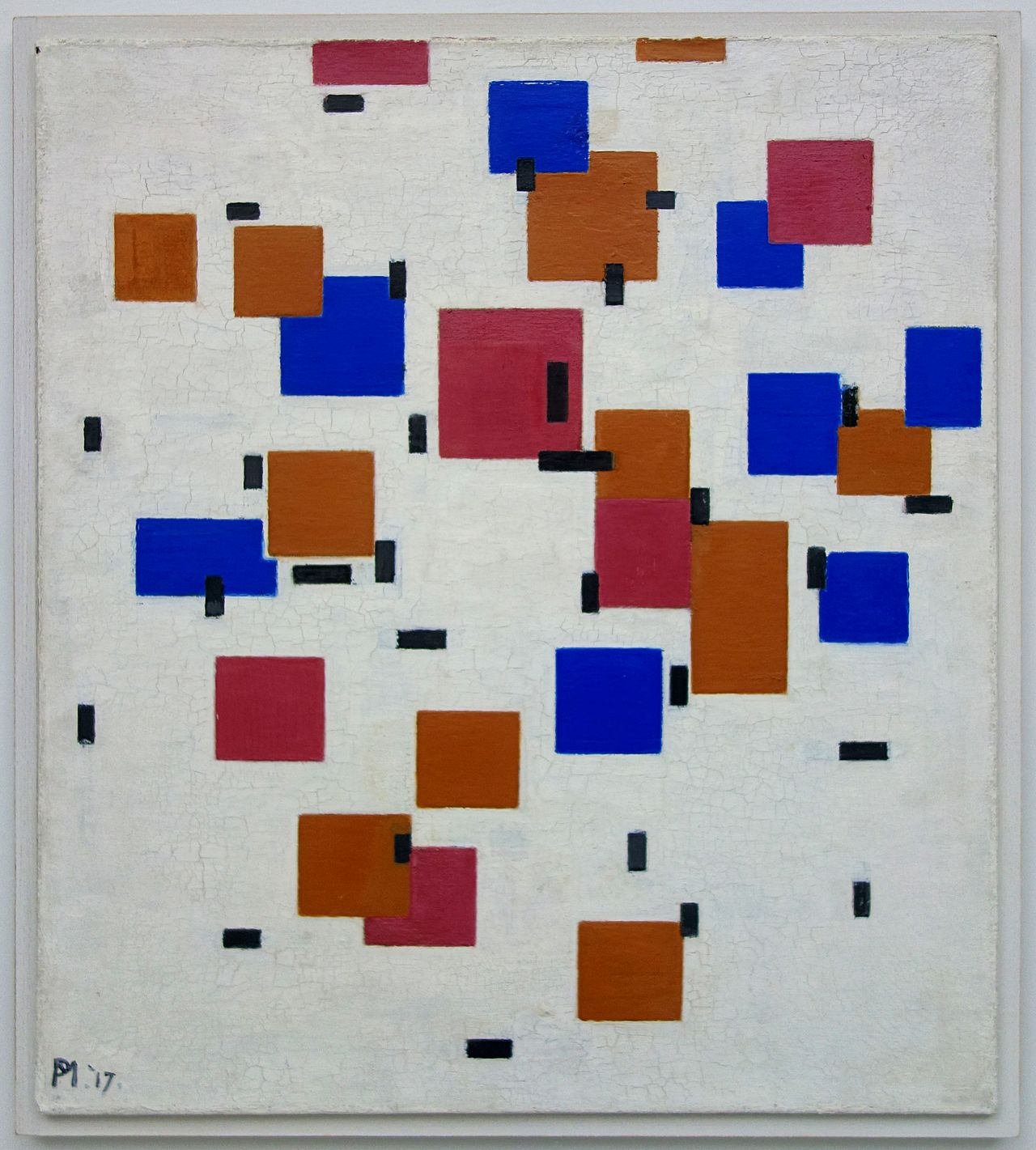

Use of Primary Colors and Noncolors

In practice, this meant the exclusive use of primary colors—red, blue, and yellow—alongside noncolors such as black, white, and various shades of gray. This restriction was not perceived as a limitation by De Stijl artists, but rather as a means to achieve visual and conceptual clarity in abstract painting, furniture, and De Stijl architecture.

Geometric Forms and Orthogonal Lines

These colors were employed in flat planes—bordered by straight, black horizontal and vertical lines that did not intersect at any angle other than a right angle. Consequently, the movement’s characteristic geometric forms and orthogonal lines conveyed a sense of mathematical precision and spatial order, in stark contrast to the more traditional, organic forms found in naturalist and figurative art.

Philosophical Underpinnings

The philosophical underpinnings of De Stijl were rooted in a search for universal values and a harmonious order, which the movement’s proponents believed could be attained through this new, abstract visual language.

They posited that through the reduction of form and color to their essentials, art could transcend cultural and individual particularities—reaching a universal mode of expression that could be understood by all. This concept of universal harmony and order was intrinsic to the movement’s goals—reflective of a broader idealistic yearning for a unified and improved society.

Relationship with Other Art Movements

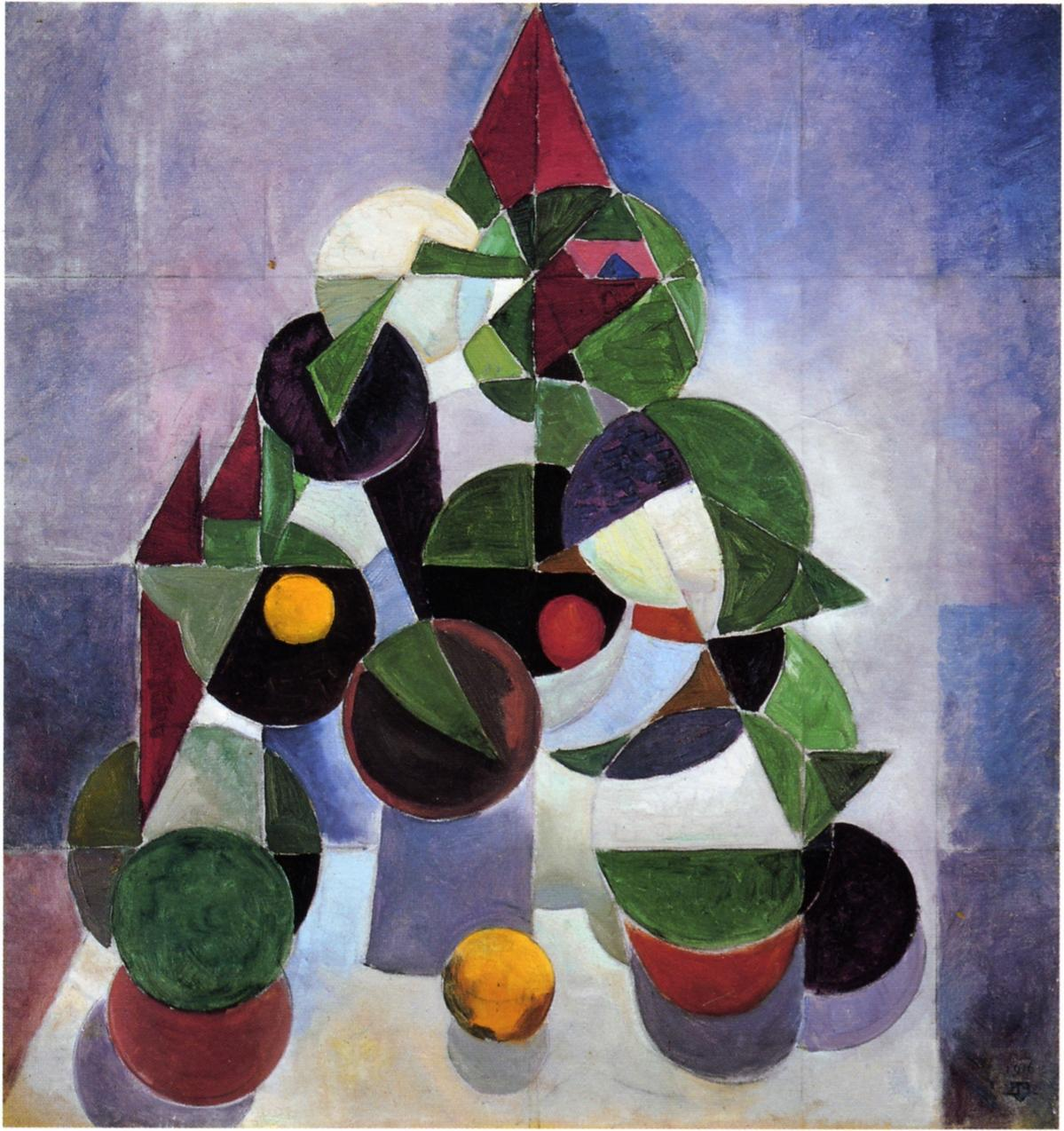

The relationship of De Stijl to its contemporaries—such as Cubism and Futurism—is complex. While all three movements sought to break with traditional art forms, De Stijl was distinct in its philosophical leanings and its purist approach to abstraction.

Unlike Cubism, which fractured and reassembled the pictorial space, De Stijl aimed for a clarity and reduction that could reveal an underlying, essential structure. And whereas Futurism celebrated dynamism and the machine age, De Stijl’s aesthetic was static, serene, and aimed at achieving a timeless equilibrium.

Nonetheless, De Stijl shared with these movements a commonality in the pursuit of a new art that could reflect and shape the modern experience.

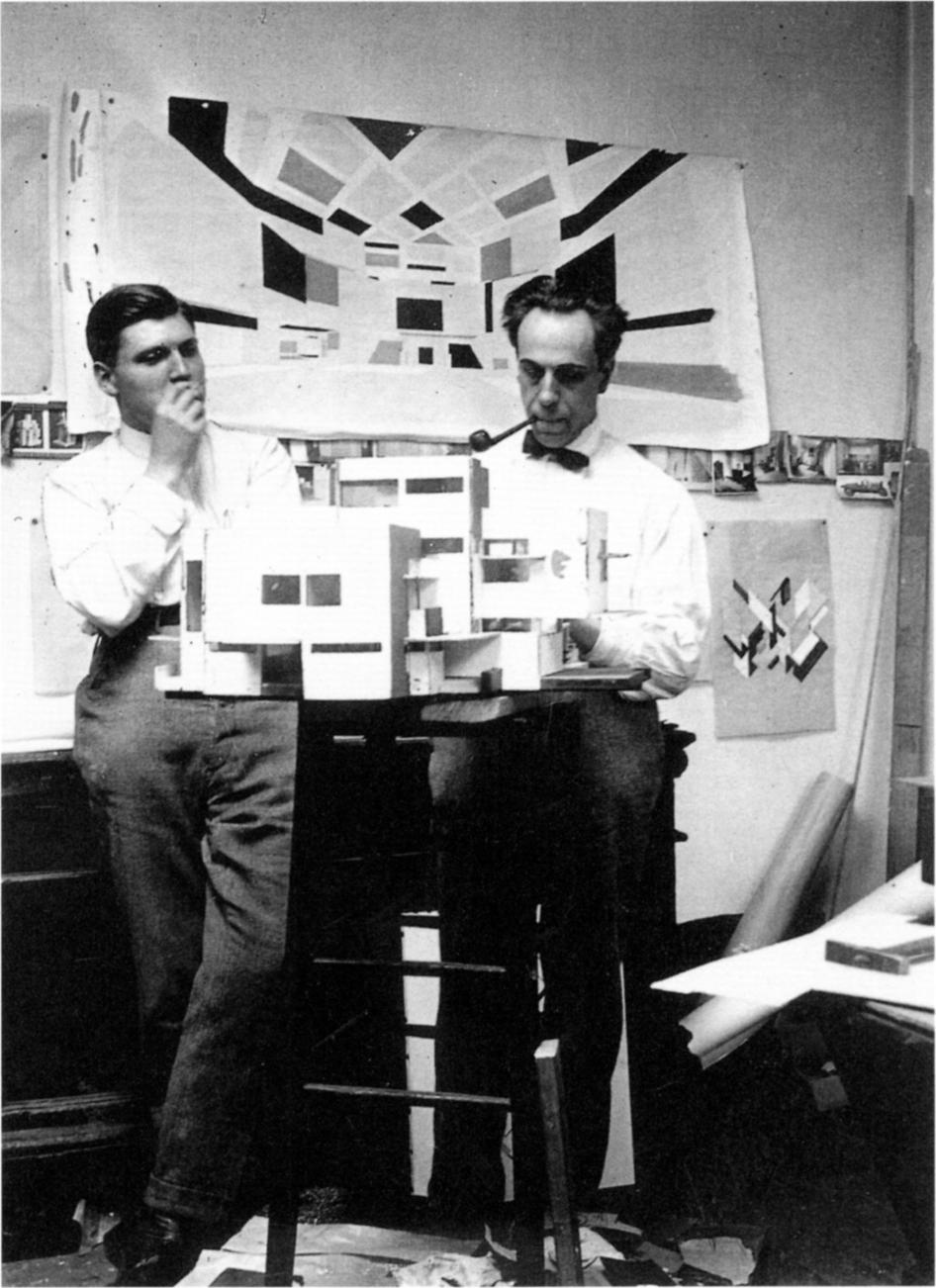

The De Stijl Group

The De Stijl group was a collective of Dutch artists and architects that formed in the Netherlands in 1917. The term “De Stijl” is Dutch for “The Style”—also known as neoplasticism. This movement was officially established with the publication of the “De Stijl” journal, which was founded and edited by Theo van Doesburg. The group included artists such as Piet Mondrian, Vilmos Huszár, and Bart van der Leck, as well as architects Gerrit Rietveld and J.J.P. Oud.

De Stijl proposed a radical simplification of formal means to reflect a new spiritual harmony—an ethos provoked by the desire for a ‘universal aesthetic’. They emphasized an abstract, reductionist aesthetic centered on the basic visual elements of simple geometric forms, lines, and primary colors. The De Stijl artists aimed to achieve a visual language that was devoid of individual expression and could be universally understood—reflecting their philosophical beliefs which were influenced in part by Theosophy and a fascination with the technological progress of the time.

The journal “De Stijl” became the mouthpiece for the group’s theories and became a platform for its members to publish essays, commentary, and designs that exemplified the movement’s ideals. Through its publications—which continued until 1931—the journal helped to spread the movement’s philosophy and aesthetic principles to an international audience. Van Doesburg actively promoted De Stijl abroad through lectures, exhibitions, and by establishing contacts with other avant-garde movements of the period.

Internal Disputes and Divergence within the Movement

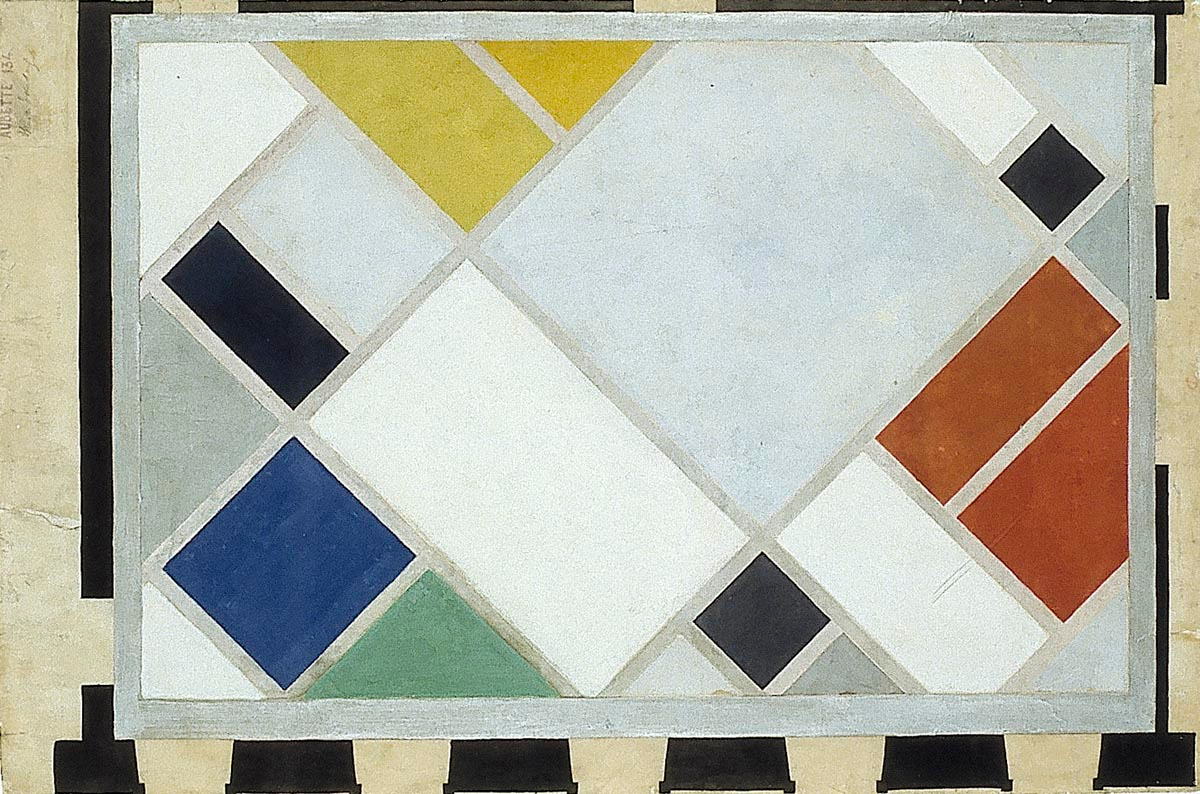

Despite the unity of purpose in the beginning, the group was not without internal disputes, and tensions arose particularly between Mondrian and van Doesburg. These disagreements centered around the interpretation of the movement’s principles—particularly after van Doesburg introduced the diagonal line in his work—which Mondrian saw as a betrayal of the movement’s strict use of horizontal and vertical lines.

The influence of the group was far-reaching—impacting not only the visual arts but also design, typography, and architecture. Its principles can be seen in the later works of the Bauhaus and in the development of the International Style in architecture. Though the group disbanded in the early 1930s, the ideals of De Stijl continued to permeate modern art and design practices throughout the 20th century and beyond—informing minimalist aesthetics and continuing to inspire artists and designers around the world.

A Closer Look at Major Artists and Contributors

Piet Mondrian

Piet Mondrian—a preeminent figure of De Stijl—was born in 1872 in the Netherlands. His artistic evolution began with landscape painting—where he showed an early interest in color and form. As he delved into his craft, Mondrian’s work transitioned from impressionistic and expressionistic styles to ultimately embrace complete abstraction.

His journey towards abstraction was partly influenced by his exposure to Cubism in Paris, but unlike Cubists, Mondrian sought to eliminate any reference to the external world in his work. He developed a distinctive approach that came to be synonymous with the movement—characterized by a grid of vertical and horizontal lines and the use of primary colors in his De Stijl paintings.

Key works such as “Composition with Red Blue and Yellow” (1930) encapsulate this phase and have become iconic—representing the ideals of harmony and the balance between the universal and the individual, the dynamic and the static.

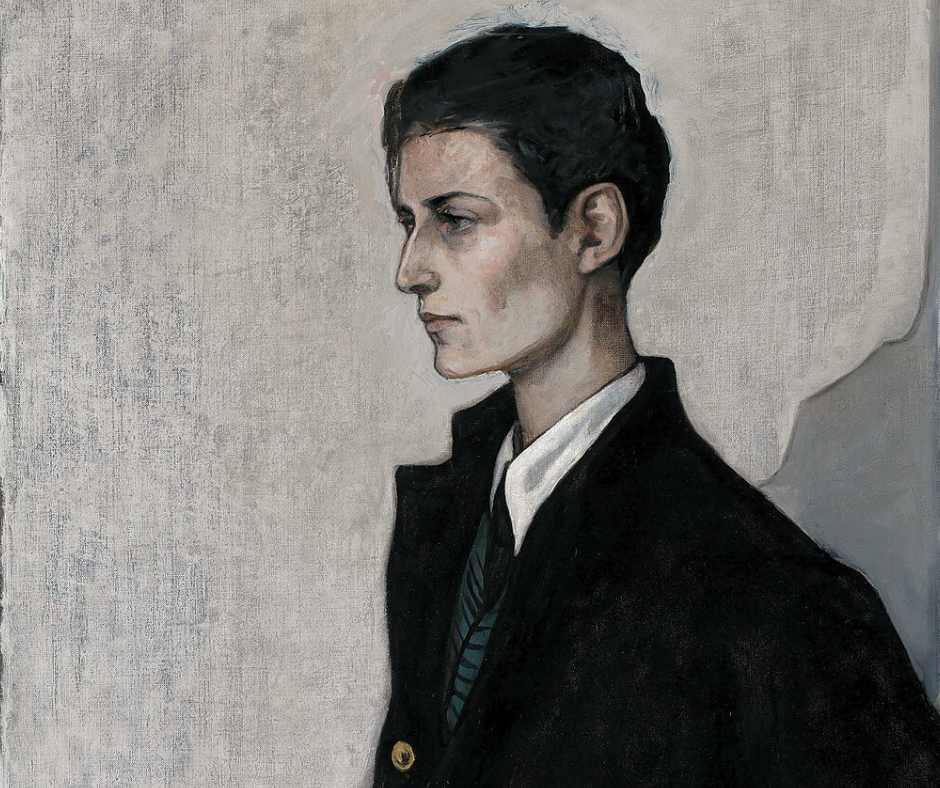

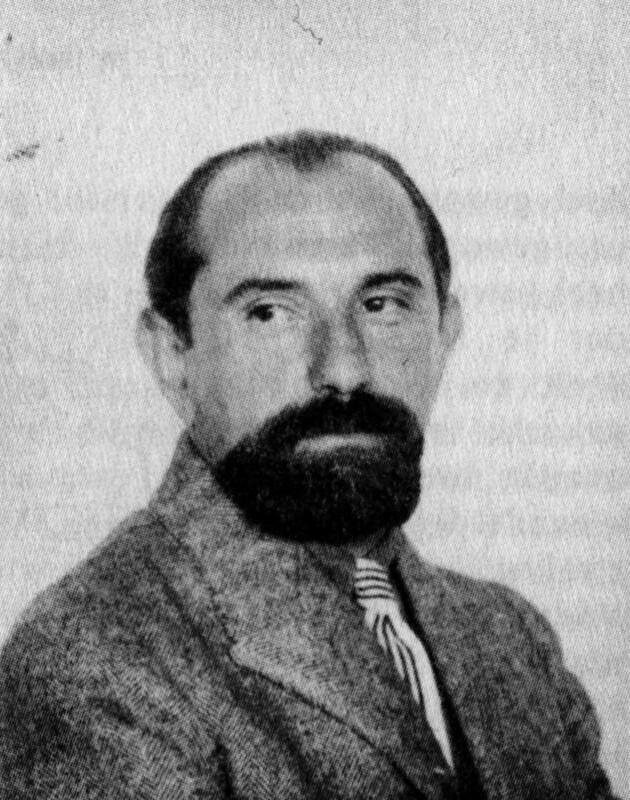

Theo van Doesburg

Theo van Doesburg—the co-founder of the De Stijl movement who is often credited with the movement’s first works—was crucial both as an artist and a theorist. Born in 1883, he was instrumental in formulating the principles of the movement and propagating its ethos through his writings and artwork.

Van Doesburg was a polymath who practiced painting, writing, and architecture. His role as an editor of the De Stijl journal allowed him to communicate the group’s theories and expand their influence. He was particularly instrumental in spreading De Stijl’s ideas internationally, through his lectures in Europe and correspondence with artists and architects—thus fostering the movement’s growth beyond the confines of Dutch borders.

Other Notable Figures

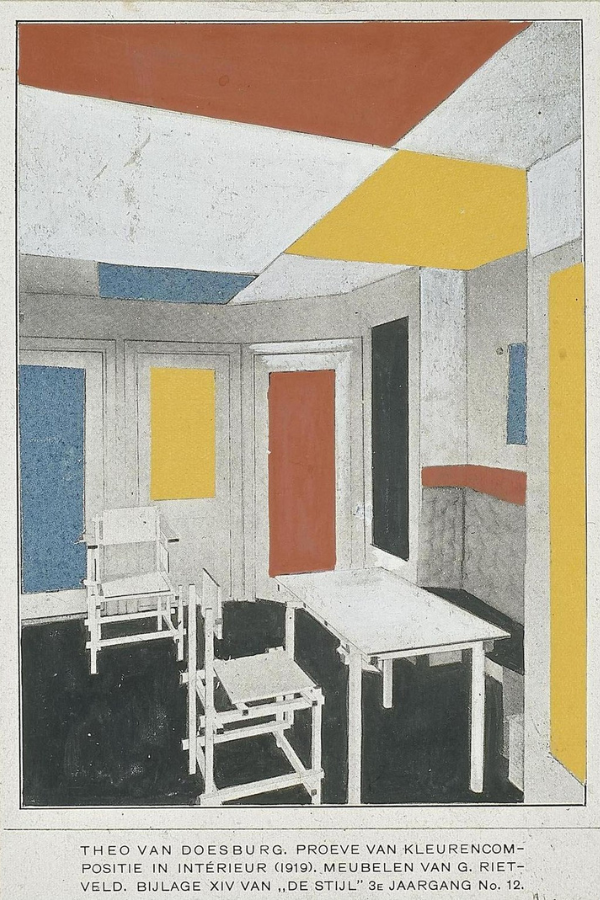

Other notable figures within De Stijl also made significant contributions across various domains. Gerrit Rietveld—an architect and furniture designer—applied De Stijl principles to his work in three dimensions. His Red and Blue Chair (1917) is emblematic of the movement’s aesthetic—translating the abstract into functional design. His Schroder House (1924) in Utrecht is another exemplary De Stijl creation—embodying its visual language in an architectural form.

Graphic designer and painter Vilmos Huszár and artist Bart van der Leck also had substantial impacts on De Stijl’s visual and conceptual framework. Huszár’s contributions to graphic design included the creation of the movement’s logo and promotional materials that disseminated its unique visual style. Van der Leck’s use of primary colors and simplified forms in his paintings was influential in defining De Stijl’s direction in its nascent stages.

Architect J.J.P. Oud’s work in the realm of urban development and residential De Stijl architecture brought this international style into the public domain. His designs for worker housing in the Dutch city of Rotterdam displayed the movement’s aesthetic and social ideals—showcasing how these could be applied within an urban context.

His commitment to De Stijl’s philosophy was reflected in his buildings’ clear lines, primary color use, and balanced proportions—leaving a lasting legacy on modernist architecture.

De Stijl’s Influence on Various Disciplines

De Stijl’s influence extended far beyond painting—profoundly impacting disciplines such as architecture, furniture design, and the broader visual arts. In architecture, De Stijl’s principles advocated for an aesthetic that was closely aligned with the ideals of form following function—a concept that would later be echoed by the Bauhaus and the Modern Movement.

Architecture

Beyond modern and contemporary art, architects associated with De Stijl applied a visual language that emphasized geometric forms, planes intersecting at right angles, and a clear structural logic. This approach resulted in iconic De Stijl buildings like the Rietveld Schröder House—designed by Gerrit Rietveld—which showcased an interplay of flat surfaces and primary colors and articulated a vision of living space as a flexible, integrated environment rather than a series of compartmentalized rooms.

Beyond the Fine and Applied Arts: Furniture Design

In the realm of furniture design, the movement saw a synthesis of utilitarian purpose and aesthetic principle. Gerrit Rietveld’s Red and Blue Chair stands as a seminal example of De Stijl’s furniture design, capturing the movement’s fundamental characteristics—primary colors, straight lines, and the visible display of construction.

The chair’s design was groundbreaking for its time, eschewing ornamentation and embracing a form that directly reflected its function. De Stijl furniture was not merely a functional product but an embodiment of the movement’s philosophical leanings—aiming to harmonize space through design.

Pushing the Modern Art Movement Towards Pure Abstraction

Within the visual arts, De Stijl was pivotal in accelerating the shift towards pure abstraction. The movement’s artists—such as Mondrian and Van Doesburg—strove to eliminate representational elements from their work—focusing instead on the composition of the canvas as a field of tension and balance between lines and colors.

This radical simplification and abstraction aimed to express the harmony underlying the visible world. In the commercial and graphic design sectors, De Stijl’s concepts were integrated into typography, poster design, and advertising—influencing the visual language of the 20th century. The movement’s clarity of design and its reductive aesthetic principles lent themselves to the development of corporate identities and graphic design that required clear, universal communication.

This was reflected in the work of figures like Vilmos Huszár, whose graphic designs for the movement were pioneering in their minimalistic and abstract qualities.

Challenges and Evolution within the Movement

De Stijl—while unified by a common goal of aesthetic purity and abstraction—was not immune to internal conflicts and ideological divergences among its members. A significant rift within the movement emerged between two of its leading figures: Piet Mondrian and Theo van Doesburg.

The Split Between Mondrian and van Doesburg

This split was epitomized by van Doesburg’s introduction of the diagonal line in his artwork—a fundamental departure from the strict horizontal and vertical lines espoused by Mondrian. Mondrian perceived the diagonal as a regression towards a dynamic that contradicted the serene, static equilibrium he sought in his work.

This ideological disagreement led to Mondrian’s eventual disassociation from the group in 1923. The impact of such individual differences was profound—illustrating the challenges of maintaining a cohesive philosophical and artistic direction within a collective.

The Gradual Dissolution of De Stijl

The dissolution of De Stijl was gradual—attributable to various factors including the death of key members and the changing landscape of the European art world. The onset of economic challenges in the post-World War I era, shifting trends in art, and the advent of other avant-garde movements contributed to De Stijl’s decline.

Members of the group began to explore new directions or reverted to more individualistic practices, and as a result, the movement dissipated as a cohesive entity by the early 1930s.

The Transition of the De Stijl Movement into Other Modernist Practices

Despite its relatively brief existence, the legacy of De Stijl was perpetuated through its influence on other modernist practices. Many principles of De Stijl were absorbed into the Bauhaus school and the International Style in architecture—spreading its ethos of functionalism and geometric abstraction.

Artists and architects continued to reference De Stijl’s aesthetic in their works, ensuring that its core ideals—simplicity, abstraction, and universality—remained integral to the narrative of modern art and design. The movement’s insistence on the fusion of art and life left an indelible mark on the approach to various disciplines, from painting to architectural theory, and continued to inspire subsequent generations seeking a harmonious balance between form and function.

Lasting Legacy of the De Stijl Art Movement

The legacy of De Stijl artists is enduring and deeply embedded in the fabric of modern and contemporary art. Its principles of abstraction and reduction to fundamentals have acted as a beacon for artists seeking a visual language that transcends the complexities of form and narrative.

The influence of De Stijl artists is readily apparent in the development of Minimalism and other non-objective art movements that emerged in the mid-20th century. These movements, while distinct, share De Stijl’s devotion to purity of form and the exploration of the essential elements of color, line, and plane.

Architecturally, De Stijl’s impact was instrumental in the development of the International Style—characterized by an emphasis on volume over mass, the use of lightweight, industrial materials, and the rejection of unnecessary ornamentation. The style was propagated globally through the work of architects such as Le Corbusier and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe—who embraced De Stijl’s aesthetic principles and carried its ethos into their groundbreaking designs.

In the realm of minimalist and abstract art movements of the mid-20th century, the ghost of De Stijl’s influence looms large. Artists who pursued Minimalism found affinity with De Stijl’s emphasis on the essential qualities of the artwork, its structure, and form. The movement also presaged later developments in Color Field painting and abstract expressionism, which—while diverging from De Stijl’s strict geometric constraints—still echoed its fascination with the emotional resonance of color and form.

The echoes of the De Stijl art movement continue to reverberate in contemporary design and popular culture. Its aesthetic has been appropriated and reinterpreted in various forms—from the sleek lines of modern furniture to the layout and typeface choices of 21st-century web design.

Even in popular media, the bold use of primary colors and simple geometric shapes can often be traced back to the influence of the De Stijl art movement. The movement’s central tenets, the search for universal values and harmonious order, remain relevant—resonating with designers and artists who continue to seek balance and clarity in their work. This ongoing inspiration is a testament to De Stijl’s profound and lasting significance in the pantheon of artistic innovation.