Flora and Fauna: Painters from the Barbizon School

Summary

Reflection Questions

Journal Prompt

The Barbizon School—a 19th-century French art movement—emerged as a collective that eschewed the formalities of academic painting in favor of direct engagement with nature. Originating in the village of Barbizon near the Forest of Fontainebleau, this group of artists pioneered plein air painting—or painting outdoors—which fostered a novel authenticity in the depiction of landscapes. This article examines the specific manner in which Barbizon painters represented flora and fauna—detailing their immersive portrayal of the natural environment. It focuses on the analysis of the techniques and thematic nuances employed by notable figures such as Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Théodore Rousseau, and Jean-François Millet—whose works collectively underscored the movement’s commitment to naturalism and the textured rendering of the rural French countryside. Learn more about the Barbizon painters and their approach to landscape painting.

Historical Context of the Barbizon School

The Barbizon School materialized in the mid-19th century—rooted in a period marked by profound socio-economic transformation. This artistic movement germinated in an era when the bucolic countryside of France began to yield to the inexorable march of industrialization and urban expansion.

Artists congregated in the small rural village of Barbizon to form a community dedicated to studying and painting the landscape and peasant life in a naturalistic manner. This confluence of artists was not a formal school but rather a collective driven by a shared inclination toward the authentic representation of nature.

The Barbizon School’s Reaction to Urbanization and the Industrial Revolution

As the Industrial Revolution reshaped the European landscape, the Barbizon painters’ canvases stood in tacit protest against the encroachment of industrialization. Their work often conveyed a nostalgia for the vanishing rural landscapes and traditional peasant life.

Through their art, they sought to capture the ephemeral qualities of light and atmosphere, the serene beauty of untamed woodlands, and the simple dignity of agricultural labor. This retreat to nature was a deliberate counterpoint to the burgeoning urban environment and its associated societal shifts.

The idealization of the rural—evident in their work—can be seen as a reaction to the dislocations brought about by urbanization—serving as a repository for the values and tranquility perceived to be under threat.

Relationship with the French Academy and the Rise of Plein Air Painting

In juxtaposition to the prevailing doctrines of the French Academy—which favored historical and mythological themes rendered with precise brushwork—the Barbizon School fostered a breakaway philosophy. The Academy’s rigid neoclassical ideals and its endorsement of studio work were challenged by the Barbizon painters’ embrace of plein air painting.

This practice of painting outdoors was revolutionary in that it defied the academic convention of carefully constructed compositions. Plein air painting allowed for direct observation—capturing the transient qualities of light and shadow—and it called for a rapid, more impulsive application of paint. T

his method not only infused their works with a sense of immediacy and dynamism but also enabled a truer, more organic interaction with the landscape—hallmarks that would heavily influence the subsequent Impressionist movement. Thus, the Barbizon School’s dedication to plein air painting was not just an aesthetic choice but a declaration of independence from the strictures of academic art—a vital step towards the modernist upheavals that would define the end of the century.

The Barbizon School’s Approach to Nature

The Barbizon School’s approach to nature was fundamentally anchored in their philosophical and aesthetic principles that prioritized the truthful representation of the natural world. Breaking from the classical tradition of idealized landscape painting, these French painters sought to capture the essence of the scenery before them with sincerity and directness. They committed themselves to more objective landscape painting than their fellow artists.

Their work rejected the embellishments and heroic grandeur typical of earlier styles in art history and instead embraced the unadorned beauty of the rural French landscape. The aesthetic of these young artists was grounded in the belief that emotional authenticity could be best conveyed through fidelity to nature’s own compositions and colors.

Techniques and Styles Used by Barbizon School Painters for Outdoor Painting

In terms of technique, the Barbizon painters were innovative in their adoption of plein air painting. These outdoor painting excursions required a quickness of execution that led to looser brushwork—a visible shift from the finely detailed, polished techniques endorsed by the Academy.

When painting landscapes, they often employed a muted palette to mirror the subdued hues observed in natural conditions, and they showed a predilection for the use of chiaroscuro to capture the dramatic effects of light and shadow found in forested scenes and twilight hours. Their sketches and studies made outdoors served as vital references for larger works, which—while sometimes completed in studios—retained the spontaneity and vigor of the initial impressions gathered from nature.

Influence of Romanticism and Realism

The influence of Romanticism on the Barbizon group is evident in their collective infatuation with nature as a source of spiritual and emotional inspiration. Romanticism’s emphasis on the sublime and the majestic aspects of the natural world resonated with these landscape painters—although their interpretation leaned more towards a gentle, contemplative reverence rather than the awe-inspiring or turbulent vistas often associated with Romantic art.

Realism, too, left its mark on the school. The Realist movement’s dedication to depicting subjects truthfully without artifice aligned closely with the Barbizon painters’ own objectives. This led to a nuanced portrayal of the everyday and commonplace in nature—often imbued with a sense of immediacy and an honest, unfiltered aesthetic.

The Barbizon artists’ commitment to capturing the reality of the landscape and rural life without romanticizing it bridged these two significant art movements. In this way, the Barbizon style paved the way for other painters of naturalism and the later developments in landscape painting.

Flora: The Barbizon School’s Depiction of Vegetation

In the oeuvre of the Barbizon School, the depiction of flora was not merely incidental but a central theme that conveyed the intimate interplay between the landscape and its vegetative elements. The artists of the Barbizon School often gravitated toward scenes of dense forests, wild thickets, and pastoral fields—capturing the various textures and forms of plant life. Their canvases frequently featured the Forest of Fontainebleau—with its sprawling trees and undergrowth—as a primary subject, highlighting the organic complexity and tranquility of these environments.

Analysis of Specific Works by Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and Other Barbizon Artists

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot—a pivotal figure within the Barbizon School—exemplified this focus on vegetation. His paintings—such as “Forest of Fontainebleau” (1830s)—reveal a delicate balance between the representation of individual trees and the forest as an encompassing, living entity. Corot’s technique often involved layering translucent glazes to achieve a luminous quality—giving his vegetation a vibrant yet ethereal presence. The interplay of light and shade was meticulously studied—with dappled sunlight filtering through leaves to create a dynamic and harmonious composition.

Other artists, like Théodore Rousseau, took a more tactile approach to flora—with works like “Edge of the Woods at Monts-Girard, Fontainebleau Forest” (c. mid nineteenth century) demonstrating a vigorous application of paint to render the rugged textures of bark and foliage. These artists employed a variety of brushstrokes to simulate the diverse surfaces found within a single view: short, stippled strokes might suggest a mossy surface, while longer, fluid strokes conveyed the soft sway of grasses or the rough, irregular outlines of rock and earth interspersed with vegetation.

Techniques Used to Convey the Textures and Movement of Plant Life

The techniques used by Barbizon School artists to portray vegetation were integral to their innovative approach to painting. They often eschewed fine brushes for palette knives, fingers, or even bunches of twigs—applying paint directly onto the canvas to create rich textures that mimicked the roughness of tree bark or the delicacy of leafy canopies.

This textural realism invited the viewer to engage with the scene not only visually but also through an implied sense of touch. Furthermore, the color choices were usually restrained and derived from natural pigments, which enhanced the realism of their vegetal subjects and underlined the unity between the flora and the earth from which it sprang.

Through these methods, the artists of the Barbizon School advanced the portrayal of vegetation in art—emphasizing its inherent beauty and vital role in the experience of the landscape.

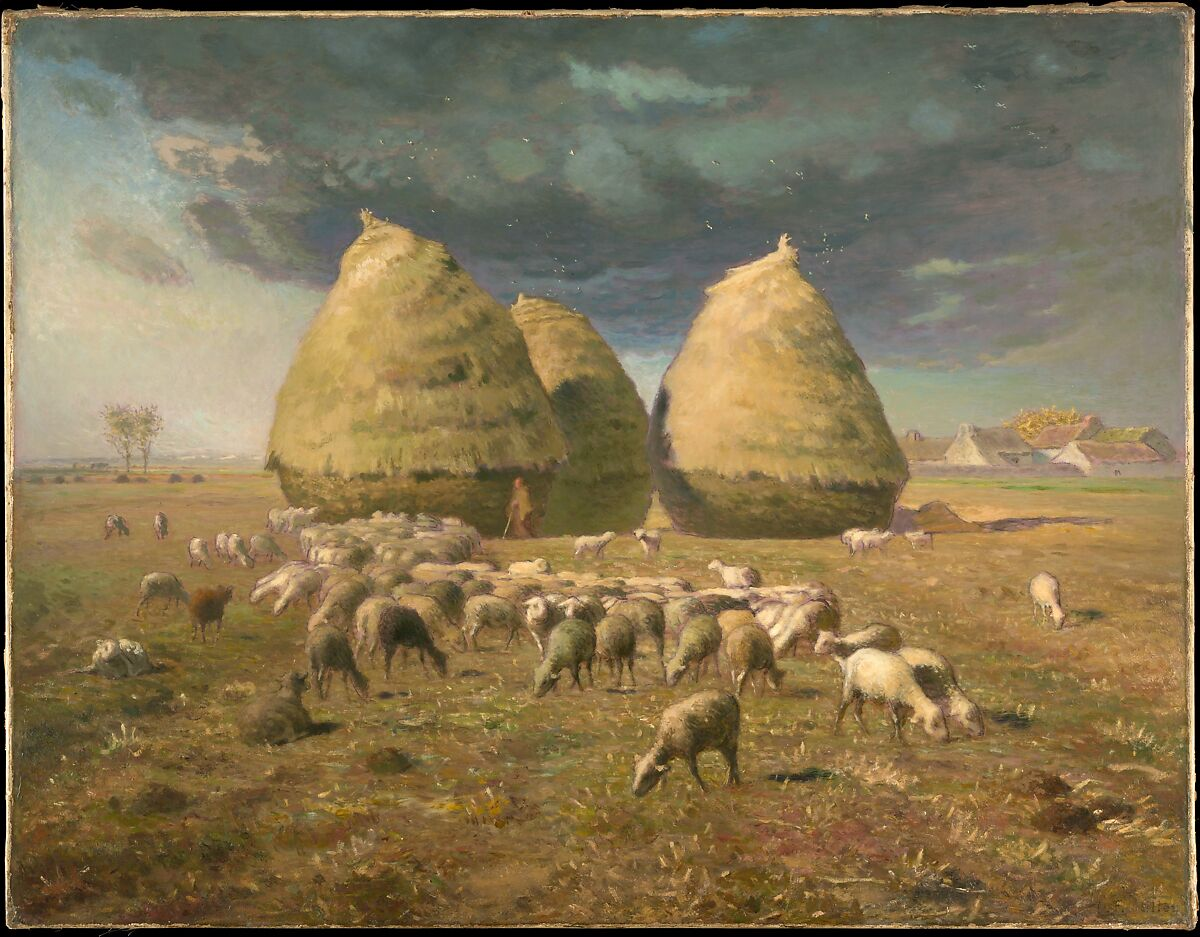

Fauna: Animals in the Works of the Barbizon Painters

Animals figured prominently in the works of the Barbizon painters—serving not only as compositional elements but also as symbols of the rural life and the untrammeled state of nature. The painters of this school frequently included animals to imbue their landscapes with vitality and to reflect the harmonious existence between wildlife and the environment.

In many of their works, animals are depicted as an integral part of the rural economy, while in others, they represent the wildness and purity of nature untouched by industrial progress.

Examination of Works by Charles-François Daubigny and Rosa Bonheur

The paintings of Charles-François Daubigny are illustrative of the Barbizon School’s nuanced approach to incorporating fauna. Daubigny’s “The Sheepfold, Moonlight” (1856-1860) encapsulates this—showing sheep as part of the cycle of life and sustenance in the countryside.

When portraying animals, the French painter to evoke a sense of calm and bucolic serenity—with the creatures often blending harmoniously into their surroundings. The luminosity of moonlight and the tranquil repose of the flock in this painting underscore a peaceful coexistence within the natural world.

Rosa Bonheur—though not a member of the Barbizon School—shared its ethos and commitment to realism in her depictions of animals. Bonheur’s “Plowing in the Nivernais” (1849)—for instance—showcases her meticulous observation and celebration of domesticated animals—in this case, oxen—as noble and dignified beings within the pastoral landscape.

Her work stands out for its anatomical precision and empathetic portrayal of animals—recognizing their essential role in human livelihoods.

Contrast Between Domesticated and Wild Animals

In contrasting depictions of domesticated and wild animals, the Barbizon painters often imbued their subjects with differing symbolic valences. Domesticated animals were frequently shown as emblematic of pastoral life and agricultural productivity—their presence a testament to the symbiotic relationship between humans and nature.

Conversely, the portrayal of wild animals carried a sense of untamed beauty and freedom, often standing as a silent protest against the encroaching industrialization that threatened their habitats. Wild animals—when depicted—were often shrouded in the mystery of the forest depths or caught in moments of undisturbed life—emphasizing their existence beyond human control and intervention.

This dual representation reflects a broader thematic concern of the Barbizon School: the meditation on the balance between human cultivation of the land and the preservation of nature’s untamed state. Through their artwork, the Barbizon painters preserved a snapshot of this equilibrium at a time when it was beginning to tilt inexorably toward modernity and mechanization.

Notable Painters from the Barbizon School and Their Contributions

Théodore Rousseau stands as a central figure in the Barbizon School—acclaimed for his forest scenes that are considered some of the most evocative depictions of natural landscapes of his time. Rousseau’s commitment to capturing the character of the Forest of Fontainebleau is manifest in the detailed and textured portrayals of trees, paths, and underbrush.

His painting “The Forest in Winter at Sunset” epitomizes his ability to convey the dense and entangled woodland interiors with a deep understanding of light and atmospheric effects. Rousseau’s dedication to naturalism and his direct observation technique significantly influenced landscape painting—affirming the Barbizon School’s emphasis on the emotive power of nature.

Jean-François Millet and the Integration of Human, Flora, and Fauna

Jean-François Millet contributed to the Barbizon School with a distinct focus on the human element within rural settings. Millet’s works frequently depict laborers among the fields and farms—integrating human figures into the landscape in a manner that emphasizes their symbiotic relationship with the land.

In paintings such as “The Gleaners” (1857), Millet foregrounds the figures amidst vast expanses of land—subtly highlighting the connection between people, the flora they cultivate, and the fauna that inhabits these spaces. His empathetic portrayal of peasant life and the dignity he bestows upon his subjects provide a social commentary on the rhythms of rural existence—aligning human life closely with the cycles of nature.

Narcisse Virgilio Díaz and the Mystical Aspect of Nature

Narcisse Virgilio Díaz de la Peña—another prominent member of the Barbizon School—is noted for infusing his landscape compositions with a mystical quality. Díaz’s work often features forest scenes characterized by a sense of enchantment—as seen in “The Forest of Fontainebleau” (1867), where the play of light creates a dramatic and almost supernatural atmosphere.

His portrayal of nature carries a heightened sense of mood and tone, capturing the forest not just as a physical space but as a living, breathing entity imbued with spirit. The use of rich, deep colors and bold contrasts in his paintings contributes to the mystical aura—leaving viewers with an impression of nature’s profound and mysterious beauty.

Díaz’s work thus complements the Barbizon School’s spectrum by adding a layer of romanticism to the collective’s otherwise realist depiction of the landscape.

The Barbizon School’s Impact on Later Movements

The Barbizon School’s emphasis on painting en plein air and their fidelity to the direct observation of nature forged a critical link to Impressionism—a movement that would come to fully embrace and extend these principles. Impressionist painters inherited the Barbizon School’s preoccupation with natural light and transient effects in the landscape genre—albeit applying these interests with a newfound intensity and a brighter palette.

Painters like Claude Monet were influenced by the Barbizon artists’ studies of landscape and atmosphere—which informed their own explorations into capturing the fleeting qualities of light. Moreover, the informal brushwork and the emphasis on the sensory experience of the landscape seen in Barbizon art can be seen as a precursor to the Impressionists’ revolutionary techniques.

The Legacy of Naturalistic and Landscape Painting

The legacy of the Barbizon School in naturalistic and landscape painting is profound. Their innovative approach to capturing the natural environment represented a departure from the idealized landscapes of the past—emphasizing a more truthful, unvarnished depiction of the rural landscape.

This philosophy laid the groundwork for naturalism and helped elevate landscape painting to a position of greater significance within the hierarchy of genres in Western art. The Barbizon School demonstrated that landscapes did not merely serve as backdrops to historical or mythological scenes but were worthy subjects in their own right—capable of conveying profound meaning and beauty.

Continued Relevance in Contemporary Environmental Art

In contemporary environmental art, the influence of the Barbizon School is subtly pervasive. Today’s environmental artists often engage with themes similar to those of the Barbizon painters—such as the examination of human interactions with nature and the advocacy for its preservation.

The Barbizon practice of engaging directly with the landscape resonates with contemporary artists who create site-specific works that highlight environmental issues or celebrate the natural world’s intrinsic value. Additionally, the Barbizon School’s tendency to portray nature authentically without embellishment is echoed in current artistic endeavors that seek to draw attention to the true state of natural environments in an age of ecological crisis.

The relevance of the Barbizon School today underscores not only the timelessness of their aesthetic achievements but also the enduring significance of their environmental concerns. Their work continues to inspire artists to consider the relationship between humanity and the natural world—a contemplation that remains as crucial now as it was in the 19th century.

Which Modern Art Movements Were Inspired by the Barbizon School?

The Impressionists were the most direct inheritors of the Barbizon School’s principles, particularly their practice of painting en plein air and their focus on the natural landscape as subject matter. Artists like Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro took cues from the Barbizon School’s treatment of light and atmosphere, while Édouard Manet and Edgar Degas were inspired by their realist approach to everyday subjects.

The Impressionists, however, diverged in their application of color and brushwork—often employing a brighter palette and more visible strokes to capture the transient effects of light.

Post-Impressionism in Europe

Following the Impressionists, the Post-Impressionists—although varied in their individual styles—also owe a debt to the Barbizon painters.

Artists like Paul Cézanne and Vincent van Gogh absorbed the Barbizon School’s dedication to the natural world, but each translated it into their unique language—Cézanne with his structured brushstrokes and Van Gogh with his expressive, swirling lines.

The Hudson River School and the Ashcan School in America

The influence of the Barbizon School reached across the Atlantic as well—inspiring the American Tonalists, whose moody, subdued landscapes with a limited palette can be seen as an extension of the Barbizon aesthetic.

Artists such as George Inness and James McNeill Whistler created works that evoke the emotional depth and tonal harmonies found in Barbizon paintings.

Additionally, the Barbizon School had a significant impact on the development of realism in American art—influencing the Hudson River School and later the Ashcan School, whose members sought to depict the reality of life, whether in bucolic settings or in urban environments.

The Itinerants in Russia

In late nineteenth-century Russia, the Itinerants (or Peredvizhniki)—a group of realist painters who formed an artists’ cooperative in rebellion against academic restrictions—shared the Barbizon School’s commitment to the truthful depiction of nature and the human condition. Their traveling exhibitions brought the aesthetic ideals akin to those of the Barbizon painters to a wider public—thus democratizing art.

The Fauves and Expressionists in Europe

Even into the 20th century, echoes of the Barbizon School could be seen in the work of the Fauves and the German Expressionists, who—although diverging significantly in style—still reflected the Barbizon commitment to personal expression through the medium of the landscape.

The broad reach of the Barbizon School underscores its importance in the transition from traditional to modern art. By emphasizing direct observation, emotional depth, and a strong sense of place, the Barbizon painters left an indelible mark on the trajectory of art history—influencing generations of artists who sought to capture the essence of the world around them.

Final Thoughts

The Barbizon School’s portrayal of flora and fauna marked a seminal moment in the evolution of landscape painting—characterized by a faithful representation of the natural world. The artists of this school captured the essence of the French countryside—forging an indelible connection between the viewer and the lush forests and the diverse creatures that inhabited them.

Their work provided a foundational shift away from idealized conceptions of nature—emphasizing instead the honest and direct observation of the environment. As we reflect upon the legacy of the Barbizon School, their profound influence becomes apparent not only in the subsequent movements that drew from their techniques and motifs—such as Impressionism, but also in their work’s lasting appeal.

The allure of the Barbizon School endures, their canvases continuing to resonate with audiences who find beauty and relevance in the School’s unvarnished tribute to nature—a testament to the timeless and universal appeal of the natural world in art.