Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz: The Nun of New Spain Who Was Also a Self-Taught Scholar

Summary

Reflection Questions

Journal Prompt

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz was one of the most extraordinary figures in the history of New Spain, now known as Mexico. Born in the mid-17th century, she navigated the confines of her era to emerge as a nun, self-taught scholar, and a luminous intellect of her time. Her unwavering dedication to the pursuit of knowledge, despite the stringent restrictions placed on women, marks her as a pioneering proto-feminist whose legacy transcends the boundaries of time and geography.

As a key figure in Spanish literature, her extensive body of work, ranging from poignant poetry to compelling plays and insightful essays, continues to be celebrated for its depth, wit, and critical engagement with societal norms. Sor Juana’s life and legacy exemplify an ongoing struggle for intellectual freedom and gender equality, making her an enduring symbol of resilience and brilliance in the face of adversity. Read on to learn all about what Sor Juana wrote and thought below.

The Early Life and Education of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz was born in 1648 in San Miguel Nepantla, a small village located within the viceroyalty of New Spain. Her early years were spent in this rural setting, which was marked by the rich cultural tapestry of post-conquest Mexico.

Raised in a colonial society where the Spanish crown and the Catholic Church wielded significant influence, Sor Juana’s upbringing was nestled in a world where indigenous traditions intersected with European colonial norms. Her family, though not wealthy, recognized her intellect early on, setting the stage for her unparalleled quest for knowledge.

Her Thirst for Knowledge and Self-Education

From a remarkably young age, Sor Juana exhibited an insatiable thirst for learning. She was known to have started reading from her grandfather’s library before she was even fully proficient in writing, devouring every book she could lay her hands on. This early self-directed education was unusual for women of her time, who were typically denied formal education.

Sor Juana’s intellectual pursuits were largely autodidactic, driven by her own curiosity and determination. She mastered Latin by the age of three, wrote her first poem at eight, and delved into subjects ranging from philosophy and history to science and theology, areas most women of her era were systematically excluded from.

Her Move to Mexico City and Life in the Viceregal Court

Sor Juana’s prodigious talent did not go unnoticed for long, and her circumstances took a significant turn when she moved to Mexico City, the heart of New Spain. There, she became part of the viceregal court, serving as a lady-in-waiting. This period was crucial for her intellectual development and social standing.

The viceregal court was a hub of cultural and intellectual activity, providing Sor Juana with unprecedented access to scholars, theologians, and a vast array of learning opportunities not available to most women of her time. Her time at court allowed her to engage in scholarly debates and further her self-education, setting the foundation for her later works and contributions to literature and philosophy.

Sor Juana’s Religious Life

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz’s decision to join a convent was driven by her unyielding desire for intellectual freedom rather than a devout calling to religious life. Faced with the limited options available to women of her time—marriage or the convent—she chose the latter, viewing it as a means to continue her studies uninterrupted by the societal expectations placed on women.

Sor Juana entered the convent of the Order of St. Jerome in Mexico City, which was known for its leniency in allowing nuns to pursue scholarly interests. This environment was crucial for Sor Juana, as it provided a relatively liberal framework within which she could explore her intellectual passions without the constraints typically imposed on women of the 17th century.

How the Convent Provided Her with the Time and Space for Scholarship

The convent effectively became Sor Juana’s sanctuary for intellectual pursuit. Within its walls, she found the solitude and resources necessary to delve deep into her studies and writing. The convent allowed her access to an extensive library, and she amassed a large collection of books over the years, which were essential to her self-education and scholarly work. Moreover, her religious duties were structured in a way that afforded her significant amounts of time to dedicate to her intellectual endeavors.

This unique setting enabled Sor Juana to produce a prolific body of work, including poetry, dramatic plays, and theological essays, that would cement her legacy as one of the most important figures in Spanish literature. Her life in the convent underscored a paradox of her time: it was within the confines of a religious institution that Sor Juana found the freedom to forge a path as a formidable scholar and writer.

Her Incredible Literary Contributions

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz’s literary oeuvre is a testament to her profound grasp of the Spanish language and her versatile genius. Her work spans a wide array of genres, including lyrical poetry, dramatic plays, and reflective essays, all marked by her eloquent use of language and sophisticated rhetorical techniques.

Sor Juana’s poetry often weaves intricate metaphors and classical references with her personal insights. Sor Juana’s love poems, in particular, demonstrate her ability to navigate the complexities of the Spanish language with ease. Her plays, on the other hand, not only entertained but also subtly critiqued the social norms of her time, blending wit with moral and philosophical inquiry. Sor Juana’s essays, particularly her theological and philosophical writings, demonstrate her depth of knowledge and her capacity to engage with the intellectual debates of her era.

Themes in Sor Juana’s Work

The themes that pervade Sor Juana’s work are as diverse as her literary forms. Her love poems range from the passionate to the platonic, exploring the nuances of human emotion and the complexities of love with sensitivity and insight. A pioneering feminist voice, Sor Juana’s writings often challenge the gender norms and restrictions of her time, advocating for women’s rights to education and intellectual freedom.

Her criticism of societal norms is perhaps most boldly expressed in her essays and prose, where she confronts the hypocrisies and injustices of the social and religious institutions of New Spain. Through her work, Sor Juana emerges as a critical observer of her society, using her literary talents to question and critique the status quo.

Notable Works

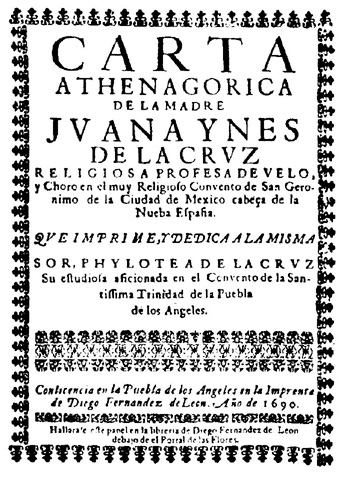

Among Sor Juana’s extensive body of work, “Respuesta a Sor Filotea de la Cruz” stands out as a cornerstone of her literary and intellectual legacy. Written as a defense of women’s rights to education and intellectual pursuit, the “Respuesta” is a powerful rebuttal to the criticisms Sor Juana faced from the church and society for her scholarly interests. In this letter, Sor Juana responded to those criticisms and eloquently argued for the moral and intellectual equality of women, showcasing her erudition, wit, and resilience.

Other notable works include her lyrical masterpiece “Primero Sueño: A Sor Juana Anthology” (First Dream), which reflects her deep philosophical inquiries into the nature of knowledge and existence, and her autos sacramentales (allegorical religious plays), which blend religious themes with her keen observations of human nature. These works, among others, cement Sor Juana’s place as a central figure in Spanish literature and a trailblazer for women’s intellectual and literary expression.

Sor Juana’s Scholarship

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz’s scholarly pursuits were both broad and deep, encompassing a range of disciplines that were uncommon for women of her time. Largely self-taught, she immersed herself in philosophy, theology, and the natural sciences, demonstrating an extraordinary capacity to absorb and synthesize complex ideas. Her philosophical inquiries delved into ethics, logic, and the nature of the universe, reflecting her engagement with both classical and contemporary thought.

In theology, she navigated the intricate debates of her day, addressing questions of faith with both reverence and critical acumen. Sor Juana’s interest in the natural sciences was equally profound; she studied astronomy, mathematics, and the physical sciences, applying her knowledge to both her literary work and her understanding of the world. This interdisciplinary approach not only enriched her writings but also positioned her as a polymath in an era when the intellectual contributions of women were often dismissed or overlooked.

Her Library and Extensive Collection of Instruments

The breadth of Sor Juana’s scholarship was supported by her extensive personal library and her collection of musical and scientific instruments, which were among the most notable in New Spain. Her library boasted over 4,000 volumes, covering a wide array of subjects and disciplines, reflecting her diverse interests and insatiable appetite for knowledge. This collection was a rarity at a time when books were expensive and access to them was restricted for most, especially for women.

Alongside her books, Sor Juana owned various musical and scientific instruments, including harpsichords, vihuelas (a Spanish string instrument), astrolabes, and globes. These tools not only facilitated her studies in music and the sciences but also served as symbols of her multifaceted intellect and her defiance of the conventional boundaries set for women’s education and engagement with the world.

Her Correspondence with Scholars and Theologians

Sor Juana’s intellectual network extended beyond the confines of the convent through her correspondence with scholars, theologians, and intellectuals of her time. These letters were crucial for her intellectual development and for the dissemination of her ideas beyond the borders of New Spain. Through her correspondence, she engaged in the vibrant scholarly debates of her era, defending her ideas and learning from the perspectives of others.

Her exchanges with prominent figures not only provided her with intellectual camaraderie but also helped establish her reputation as a formidable thinker in the broader intellectual community of the Spanish-speaking world. This aspect of her life highlights the collaborative nature of her scholarship and her ability to navigate the intellectual challenges of her time with grace and acuity.

Challenges and Criticisms She Faced from the Church and Contemporaries

Despite her towering intellect and contributions to literature and scholarship, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz faced considerable challenges from the church and the rigid societal expectations of women during her time. Living in 17th-century colonial Mexico, a society deeply influenced by the Catholic Church and Spanish colonial norms, Sor Juana’s pursuit of knowledge and her literary production were in constant tension with the roles traditionally prescribed to women.

The church, which wielded immense power, viewed her intellectual endeavors and public visibility with suspicion, often deeming her focus on secular subjects and her outspoken nature as inappropriate for a nun. Additionally, societal norms largely confined women to the domestic sphere, limiting their access to formal education and intellectual life. Sor Juana’s defiance of these constraints made her a subject of critique and controversy, challenging the very foundations of gender roles in New Spain.

Sor Juana’s work, while celebrated for its brilliance, also attracted criticism from various quarters, particularly from church officials who saw her intellectual pursuits as a deviation from her religious duties. The most notable instance of this criticism came in the form of a letter from the Bishop of Puebla, who, writing under the pseudonym “Sor Filotea de la Cruz,” admonished Sor Juana for neglecting her spiritual obligations in favor of her scholarly interests. This letter, which questioned the appropriateness of her literary and intellectual endeavors, reflected broader societal discomfort with a woman engaging in public intellectual discourse.

Sor Juana responded with “Respuesta a Sor Filotea de la Cruz,” a robust defense of her right to intellectual freedom and a critique of the gender biases that limited women’s participation in scholarly activities. Despite her eloquent defense, the pressure from the church intensified, ultimately leading her to curtail her studies and literary output. This period of her life underscores the significant obstacles Sor Juana faced in her quest for knowledge and expression, battling not just societal norms but also the institutional authority of the church.

Final Thoughts on Sor Juana’s Legacy and Lasting Impact

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz’s legacy extends far beyond her contributions to literature, casting a long shadow over feminist theory and the ongoing fight for women’s rights. Her work, once scrutinized and censured, now stands as a beacon of intellectual resistance and feminist thought. Sor Juana’s eloquent advocacy for women’s education and her critique of the gender inequalities of her time have made her an iconic figure in feminist scholarship, heralding her as a precursor to modern feminist movements.

In Mexico, she is not only venerated as one of the country’s greatest literary figures but also celebrated as a national symbol of resilience and intellectual freedom. Her image graces currency and stamps, and her birthplace and convent have become sites of cultural pilgrimage. Internationally, Sor Juana’s life and work continue to inspire a diverse array of artistic and scholarly interpretations, from plays and novels to academic treatises, highlighting her enduring relevance.

Modern celebrations of her legacy, including annual lectures, literary festivals, and academic conferences dedicated to her memory, underscore the profound impact Sor Juana has had on both literature and the global discourse on gender equality, demonstrating the timeless nature of her contributions to human thought and society.