Iconic Demolished Buildings: A Glimpse into History’s Lost Marvels

Summary

This article explores the fascinating histories of iconic buildings that have been demolished, highlighting their architectural and cultural significance. From the Temple of Artemis to the Old Penn Station, these structures represented the pinnacle of their eras. Their loss underscores the importance of preservation efforts led by historians, conservators, engineers, and architects, who work to maintain our cultural heritage. Through modern preservation techniques and community-driven policies, we can prevent the further loss of these invaluable historical landmarks.

Reflection Questions

- How does the loss of iconic buildings affect our understanding of history and culture?

- What modern preservation techniques can be employed to save endangered historical buildings in your community?

- How can public policy and community advocacy contribute to the preservation of historical sites?

Journal Prompt

Reflect on a historical building or site you have visited that left a lasting impression on you. How did the experience shape your understanding of the past? Consider what measures could be taken to preserve similar sites for future generations.

Who among us has not stood before ancient ruins or modern skyscrapers in absolute awe? Sadly, many of the world’s most incredible buildings are now gone. In this article, we explore some of the most iconic and magnificent buildings throughout history that have been demolished. From ancient wonders to architectural marvels of the 20th century, these structures were not only feats of engineering and design but also symbols of their eras. The loss of these demolished buildings represents a significant gap in our cultural and architectural heritage.

20 Iconic Buildings Lost to History

The Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, Turkey

This temple was built in 550 BCE and took 120 years to complete. After its construction, it stood double the size of the Parthenon. Beloved for its location near the sea, the marble used in its columns, and the grandeur of the temple overall, this site was set on fire by a famous arsonist before being rebuilt. Multiple attempts were made to destroy the temple, and it is now marked by a single column.

The Lighthouse of Alexandria, Egypt

Designed by Sostratus of Cnidus, the Lighthouse of Alexandria is the most famous lighthouse in antiquity. Built in 280 BCE, this tower guided ships into the harbor of Alexandria until its collapse due to an earthquake in 1303 CE. At the time, the only taller man-made structures would have been the pyramids of Giza. After its destruction, the materials were still salvageable to make a fort from the ruins of this demolished building.

The Colossus of Rhodes, Greece

This enormous statue of Helios—Greek god of the sun—was considered one of the Seven Wonders of the World. Initiated in 292 BCE and completed in 280, this featured structure was a symbol of triumph. Unfortunately, it fell to an earthquake in 226 BCE. Arabian forces later raided the site in the 600s; it was rumored to take the work of 900 camels to transport the debris. Of course, this tale is apocryphal (likely not true).

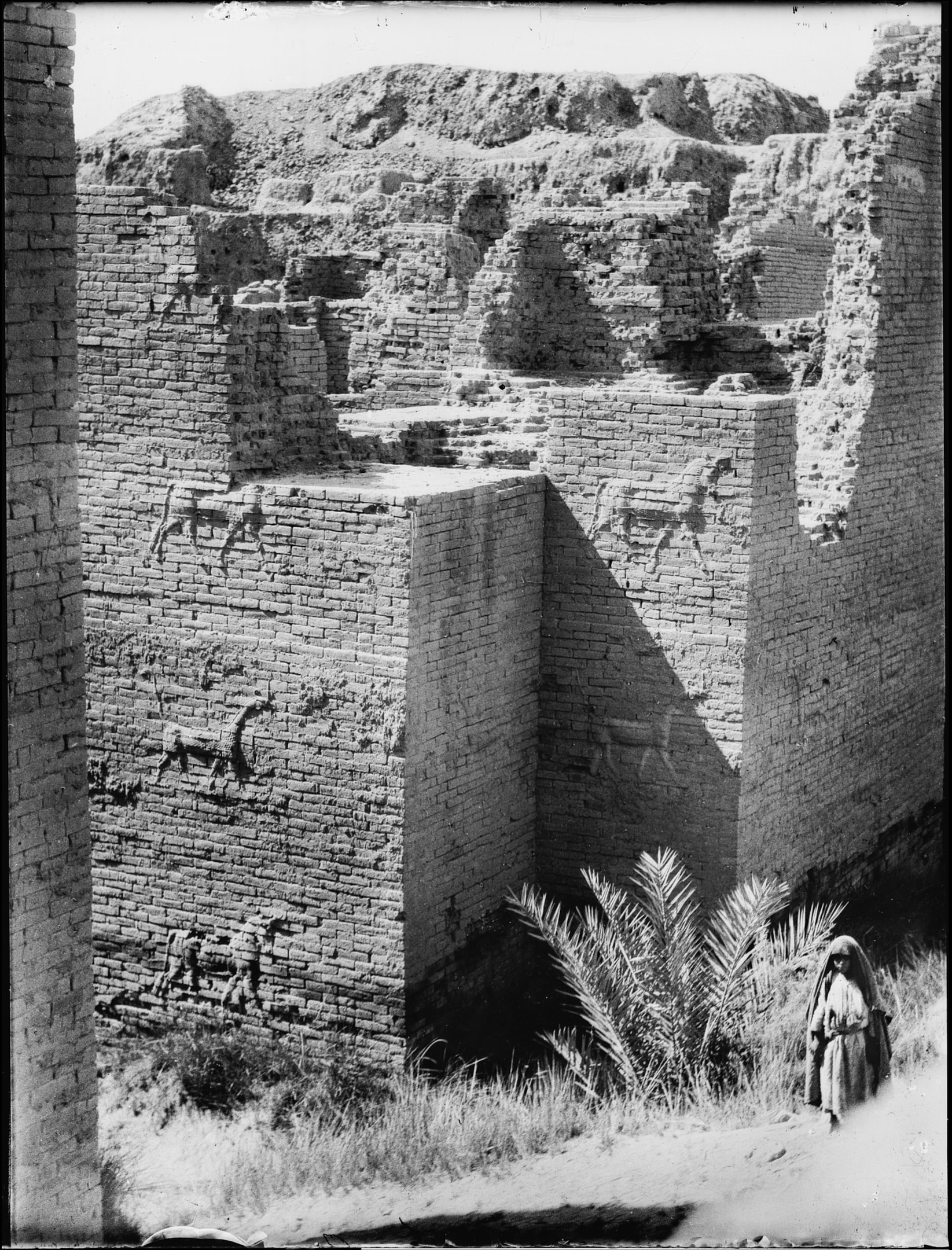

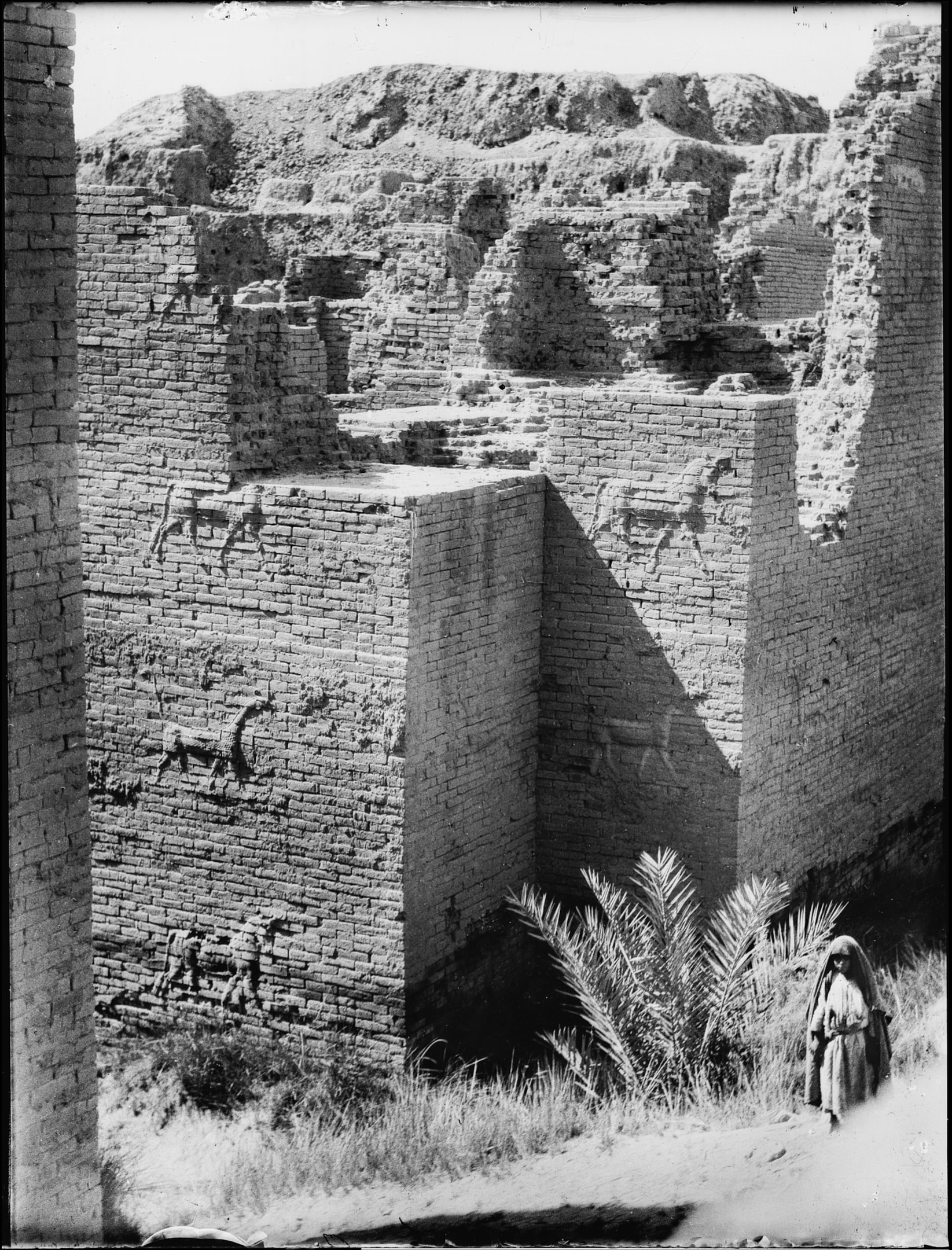

The Hanging Gardens of Babylon, Iraq

Of buildings lost to history, few have disappeared more completely or mysteriously than the Hanging Gardens, which were rumored to be built around 600 BCE. One of legend’s most enigmatic structures, they were an extraordinary feat of ancient architecture. Currently, we only have theories to revisit on the design and function of the project. T

he most common among them suggests they were a series of tiered rooftop gardens irrigated by pumps from the Euphrates. Of course, there’s ongoing debate among historians about whether the Hanging Gardens actually existed. Some believe they may have been located in Nineveh, not Babylon.

The Library of Alexandria, Egypt

In the 3rd century BCE, Alexander expressed his goal to create a universal library. Likely under Alexander the Great’s direction, the most famous library of classical antiquity was established by General Ptolemy I Soter. Once completed, it became a house of scholarly knowledge, full of major acquisitions like Aristotle’s works. While various events led to the demise of the library, the final destruction is believed by many to have happened around 272 CE.

The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, Turkey

This tomb for Mausolus was built in 353 BCE by Artemisia II. Known for its architectural splendor, this tomb stood until it was torn down by a series of earthquakes. While it stood, it was magnificent in size. Eventually the mausoleum was destroyed and its stones were repurposed as assets in local buildings.

The Statue of Zeus at Olympia, Greece

Though not technically a building, we had to include this enormous statue. Around 435 BCE, Greek sculptor Phidias sculpted a statue of Zeus, which quickly became one of the Seven Wonders. Including its base, the statue was approximately 40 feet (12 meters) high, and was plated with gold and ivory. This artistic and religious masterpiece lasted until 5th century CE—illustrating the vulnerability of even the most revered structures.

The Palace of Knossos, Crete

Crete was the principal site of the first of the Aegean civilizations. As a result, its palace became a ceremonial, political, religious, and economic center of Minoan culture. Built in 1900 BCE, the palace was a sprawling complex that played a central role in ancient Crete. The palace suffered significant damage in an earthquake around 1700 BCE but was rebuilt. It was finally destroyed around 1375 BCE—likely due to a combination of factors, including a volcanic eruption and invasion.

The Second Temple, Jerusalem

This temple once stood in Jerusalem as a holy site, but was destroyed when the Jewish people were taken into captivity. Post-exile, some were allowed to return and rebuild it. The second temple was constructed around 516 BCE and quickly became a central place of Jewish worship. The Second Temple was destroyed by the Romans in 70 CE during the First Jewish–Roman War.

The Ishtar Gate, Babylon (modern Iraq)

In 569 BCE, this final gate to the city of Babylon was built. Nebuchadnezzar dedicated the gate to Ishtar, often using it in New Year celebrations. Adorned with images of dragons and bulls, it stood as the grand entrance to this ancient city. Sadly, it was eventually demolished.

Fragments are now preserved in museums that feature many examples of ancient Mesopotamian artistry. History buffs can also visit a reconstruction of the gate in Berlin’s Pergamon Museum.

The Singer Building, New York City

The Singer Building was originally built in 1896 for the Singer Sewing Machine Corporation. In 1906, the old structure was incorporated into the new. This process was undertaken with the aim of achieving the “tallest building in the world”. Upon its completion in 1908, only the Eiffel Tower stood taller.

The Singer Building’s demolition in 1968 marked a major moment in the history of New York City. Looking back, it illustrates the relentless march of progress and the trade-offs between preserving architectural heritage and pursuing modern development.

The Old Penn Station, New York City

The Old Penn Station was built in 1910 to navigate NYC’s industrial boom. The central waiting room was the largest indoor space in the city. However, when air travel and automobiles grew in popularity, the need for the station was diminished. It was demolished in 1963 to make space for Madison Square Garden. The widespread public outcry became an avenue for the historical preservation movement in the United States, cementing it as one of the most controversial building demolitions.

Fuel your creative fire & be a part of a supportive community that values how you love to live.

subscribe to our newsletter

*please check your Spam folder for the latest DesignDash Magazine issue immediately after subscription

The Chicago Federal Building, Chicago

The Chicago Federal Building was built in 1905 by architect Henry Ives Cobb. Its dome was inspired by St. Peter’s Basilica, with neoclassical architecture and a noteworthy rotunda. A courthouse and post office for part of its life, the building was actually bombed in 1918 but was partially rebuilt. This Beaux-Arts building stood as a hub of activity and was one of the city’s largest buildings until its demolition in 1965. A building designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe replaced it.

The Morrison Hotel, Chicago

The Morrison Hotel was named after the city’s first coroner Orsemus Morrison following its construction in 1893. He had built a three-story hotel on that site in 1860. After the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, the original building was destroyed and a new one was constructed in its place. It was expanded to 21 stories and, in 1925, it underwent a major renovation and expansion—reaching a final height of 46 stories.

The Morrison Hotel was the tallest hotel in the world for a time, and it was an important symbol of Chicago’s resilience and architectural ambition until its demolition in 1965. The building was destroyed in order to make way for what is now Chase Tower.

The Second Imperial Hotel, Tokyo

The Second Imperial Hotel in Tokyo was designed and built by Frank Lloyd Wright. Completed in 1923, this building incorporated reinforced concrete and local oya stone (a type of volcanic ash), along with floating foundations of reinforced steel to enhance earthquake resistance.

An annex of the hotel burned down in initial days of the new building’s construction. In 1922, an earthquake struck—devastating much of Tokyo. Initially fearing the worst, Wright was relieved to learn that the hotel had survived the disaster largely intact. While it sustained some damage, its overall structural integrity held firm. Another annex of the building would later fall during the Great Kantō earthquake in 1923.

The hotel became a landmark and an influential model for seismic architecture, but its foundation was not supportive enough to keep the building from sinking. Due to deterioration, damage during WWII, and changing urban needs, it was eventually demolished in 1968 to make way for a new high-rise.

The Larkin Administration Building, Buffalo

The Larkin Administration Building in Buffalo, New York, was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright and completed in 1906, The Larkin was commissioned by the Larkin Soap Company as a state-of-the-art headquarters and office building. Sadly, the Larkin Administration Building fell into disrepair due to financial difficulties and neglect. Despite efforts to save it, it was tragically demolished in 1950.

The Pruitt-Igoe Housing Project, St. Louis

Designed by architect Minoru Yamasaki, the Pruitt-Igoe Housing Project in St. Louis opened in 1954 with high hopes but quickly devolved into a symbol of failed public housing. Plagued by underfunding, neglect, and social problems, the project deteriorated rapidly.

Its demolition (which was actually broadcast live on TV in 1972) marked a turning point in American housing policy—prompting a shift away from large-scale high-rises and towards alternative solutions. There is a documentary about the housing project on Amazon Prime called The Pruitt-Igoe Myth.

The Waldo Hotel, Clarksburg, West Virginia

This former building now appeals as an “abandoned site” to aficionados. It was considered one of the most luxurious hotels in the state of West Virginia. Designed by Harrison Albright and built between 1901 and 1904 with funding from Nathan Goff, Jr with the intention to entertain prominent guests who visited Clarksburg, this hotel was the hub of social life in Clarksburg for a time.

Eventually the hotel was turned into dormitories for Salem College and later, apartments. While the building technically still stands, it is vacant and uninhabitable. The city has long considered destroying the building, but it would cost quite a bit to demolish.

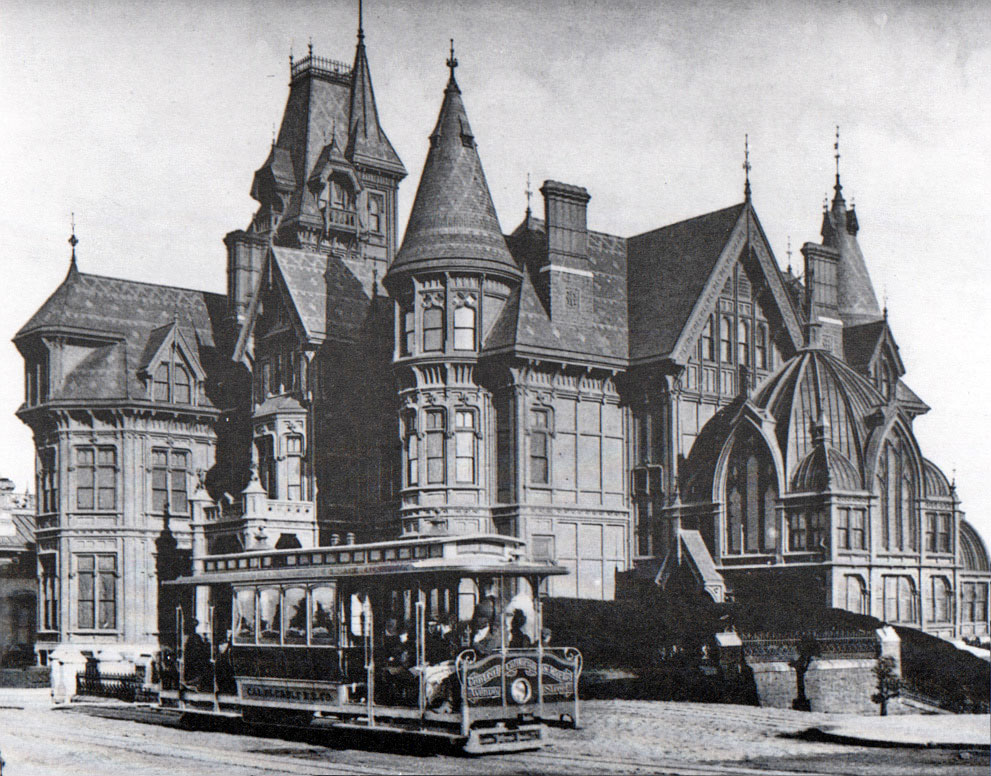

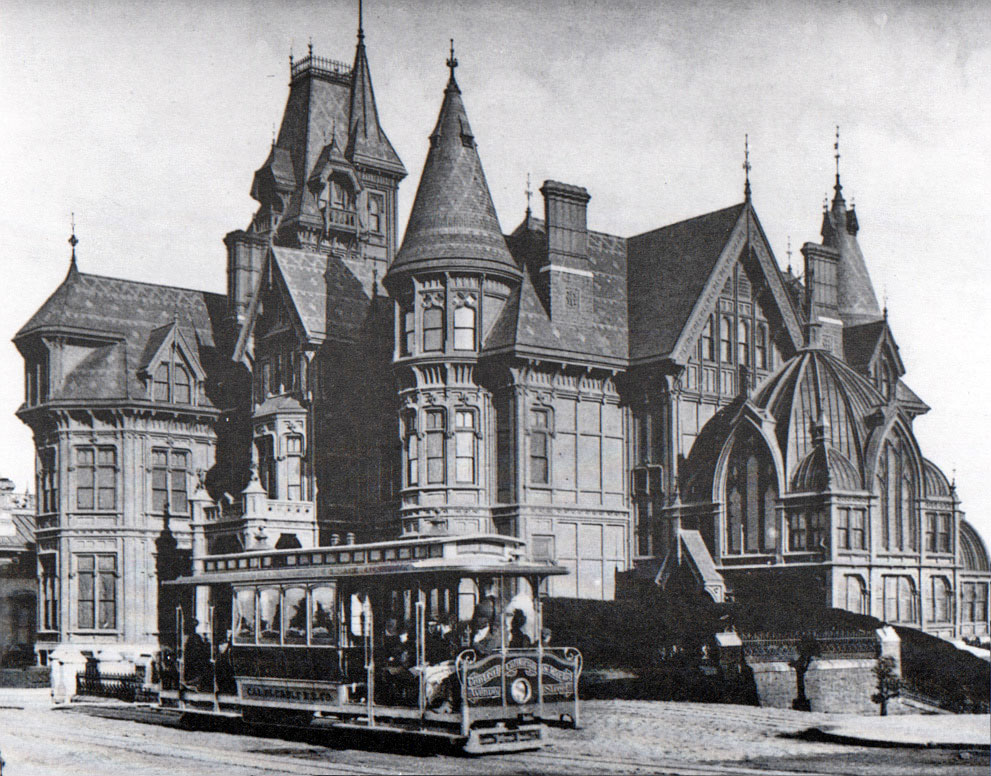

The Mark Hopkins Mansion, San Francisco

The Mark Hopkins Mansion was intended to be a family home. Construction was completed in 1878 and stood as a Gilded Age symbol of opulence. Unfortunately, Mark Hopkins himself did not live to see the mansion completed. While it technically survived a 1906 earthquake, a resulting fire days later burned it to the ground. The InterContinental Mark Hopkins San Francisco was built in its place.

The New York Hippodrome, New York City

The New York Hippodrome was once the world’s largest theater, located near Fifth Avenue. Known for its elaborate productions, it had state-of-the-art theatrical technology. The building was completed in 1905, and its demise took place in 1939 when Broadway began to take shape. The Great Depression also played a role in its closure as audiences dwindled. A parking lot and office building was later built on the site in the 1950s.

The Importance of Preservation

As all these historical sites and buildings show, preservation is invaluable. We benefit from the innovation, but buildings also often hold deep cultural, historical, and sometimes spiritual significance. Future generations benefit from experiencing these sites, gaining knowledge not possible through a page in a book or images alone. They provide important context of our past and provide resources for our future.

As is evidenced by the response to Old Penn Station’s demolition, historical preservation is a passion of many. Many historical sites have been saved by the efforts of those impacted by these losses. To save these structures is to save our history.

Modern Preservation Techniques

Architectural historians, conservators, engineers, and architects collaborate to preserve old buildings through meticulous research, careful restoration, and innovative engineering solutions. They start by studying the building’s historical significance, original materials, and construction techniques. Conservators then stabilize and repair deteriorated elements using methods that respect the original structure, while engineers address any structural issues to ensure safety and longevity.

Architects develop adaptive reuse plans, transforming buildings to meet modern needs without compromising their historical integrity. This multidisciplinary approach prevents disrepair and deterioration over time.

The Role of Community and Policy

Without communities who care about these buildings shaping policy, many historical sites would have succumbed to the unforgiving fate of a wrecking ball. Constituents must advocate for policy and legislation to guarantee these pillars of history—from the tallest building to the floor of the most intricate temple—stand the test of time. For example, the Tenth Street Historic District in Dallas—a rare Freedmen’s Town that is still a neighborhood today—is protected by policy.

Final Thoughts on Lost Historic Buildings—and How We Can Save Those We Still Have

These buildings have left an indelible mark on history and have served several purposes throughout centuries. They are markers of human innovation and reference points in our history. It is vital for all of us to do our part in advocating for preservation and public policy to make sure no more iconic buildings are lost to history.

By Jessica Collins.