Building Better Communities: Principles & Practices of New Urbanism

Summary

New Urbanism is a movement that seeks to create walkable, human-scaled neighborhoods that prioritize community, sustainability, and connectivity. Rooted in traditional urban design principles, New Urbanism offers a hopeful vision for the future of our cities by promoting mixed-use development, vibrant public spaces, and diverse housing options. This approach has transformed urban planning globally, with examples like Seaside, Florida, and the Pearl District in Portland. Communities can be retrofitted to align with these principles, and residents, especially women, are encouraged to advocate for these changes in their neighborhoods.

Reflection Questions

- How does the current design of your neighborhood impact your daily life, and what changes could improve its walkability and sense of community?

- What role do public spaces play in fostering social interaction and community engagement in your area?

- How can integrating sustainable practices and natural environments into urban design contribute to a higher quality of life for residents?

Journal Prompt

Reflect on a time when you felt a strong sense of connection to a place or community. What elements of the environment contributed to that feeling, and how can those elements be incorporated into your current neighborhood to enhance your sense of belonging and well-being?

Urban design is evolving in the United States—away from car-centric cities and toward community-focused, human-scale neighborhoods. For the last several decades, the principles of New Urbanism have been at the center of this change. Rooted in the belief that cities and towns should be designed for people, not just cars, New Urbanism emphasizes walkability, mixed-use development, and the integration of public spaces that foster social interaction. By drawing on the best aspects of historic urban design and addressing the challenges of modern urbanization, New Urbanism offers a hopeful vision for the future of our communities—one where neighborhoods are not just places to live but places to thrive. Let’s examine the principles and practices of this movement—and figure out how we can all advocate for more sustainable cities.

New Urbanism and Its Impact on Today’s Communities

New Urbanism emerged in the early 1980s as a response to the growing concerns over suburban sprawl, car-dependent communities, and the decline of vibrant, walkable neighborhoods in metropolitan regions. At its core, New Urbanism advocates for creating human-scaled, walkable communities that prioritize people over cars, blend residential, commercial, and recreational spaces, and foster a strong sense of community. The movement revives traditional development practices, drawing inspiration from the timeless qualities of historic cities and towns while addressing modern urbanization’s environmental, social, and economic challenges.

The Founders of New Urbanism

We can trace its origins to the visionary work of urban planners and architects like Andrés Duany, Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, and Peter Calthorpe. Their deep concern about the negative impacts of suburban sprawl led to the design of the groundbreaking community of Seaside, Florida in the 1980s.

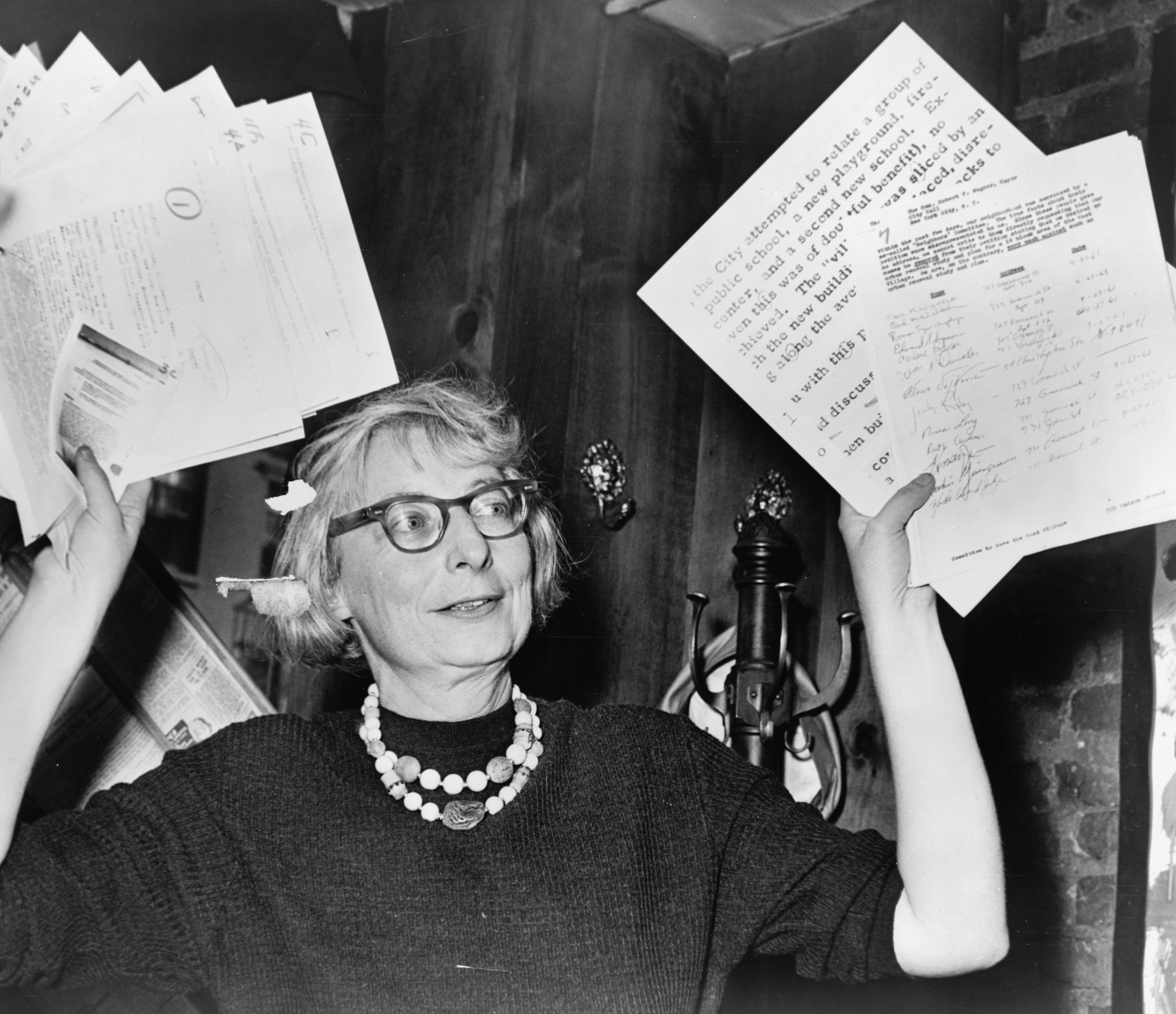

This project and the influential writings of urbanist thinkers like Jane Jacobs and Léon Krier played a pivotal role in shaping the movement’s vision of creating more livable, sustainable, and socially connected communities. Of course, Jacobs’ relationship with New Urbanism was a bit complicated, but we digress.

Recent Adaptations of New Urbanism

Today, we can see the impact of New Urbanism in communities across the United States and worldwide. The movement has influenced urban planning practices, developing more walkable, environmentally sustainable, and community-focused neighborhoods. Many projects have integrated New Urbanist principles, from small infill developments to large-scale urban revitalization efforts. Architects and urban planners designed these communities to promote social interaction, reduce car reliance, and create beautiful and functional spaces.

Awe-inspiring examples of New Urbanist communities include Seaside, Florida; Celebration, Florida; and the Pearl District in Portland, Oregon. Seaside, often hailed as the birthplace of New Urbanism, is a picturesque town that exemplifies the movement’s ideals with its walkable streets, mixed-use buildings, and vibrant public spaces. The Pearl District in Portland is a thriving urban revitalization project that transformed a former industrial area into a vibrant, mixed-use neighborhood focusing on walkability, green spaces, and public transit.

These communities, and many others like them, demonstrate New Urbanism’s enduring relevance and impact. By promoting more sustainable, inclusive, and livable urban environments, New Urbanism continues to shape the way cities and towns are designed and developed, offering a hopeful vision for the future of urban living.

17 Principles of the New Urbanism Movement and Why They Matter

Walkability

Walkability is one of the core principles of New Urbanism, aiming to make neighborhoods more livable by putting pedestrians first. Imagine strolling down a tree-lined street, where wide sidewalks invite you to walk, bike lanes keep cyclists safe, and storefronts beckon you in for a cup of coffee or a quick chat with a neighbor. The idea of walkability and access to an urban center was popularized by urban planners like Jeff Speck, who advocates for designing cities that prioritize people over cars. When neighborhoods are walkable, they become more than just a collection of houses—they become places where life happens.

New Urbanism focuses on walkability because it fosters a sense of community and enhances the quality of life. When people can walk to work, school, or the local grocery store, they’re more likely to engage with their neighbors and participate in community activities. It also promotes health and wellness, reducing the need for car travel, which can lower pollution and traffic congestion. In essence, walkable neighborhoods are more sustainable, connected, and enjoyable places to live, reflecting New Urbanism’s vision of creating human-centered communities that thrive.

Mixed-Use Development

New Urbanism also has very different development regulations and zoning laws. Mixed-use development is a cornerstone of New Urbanism, blending residential, commercial, and recreational spaces within a single neighborhood. Picture living in a community where your favorite coffee shop is just downstairs, the grocery store is a short stroll away, and a park where you can unwind is right around the corner. This concept breaks away from the traditional zoning practices that separate different land uses, encouraging a more integrated approach to urban planning. The idea is to create lively, convenient, and self-sufficient neighborhoods, reducing the need for long commutes and fostering a more sustainable way of life.

New Urbanism’s emphasis on mixed-use development stems from the desire to create vibrant, dynamic communities that cater to diverse needs. Integrating different uses into the same area allows residents to enjoy a more convenient and connected lifestyle where everything they need is within reach. This approach not only enhances the livability of neighborhoods but also promotes economic vitality by supporting local businesses and reducing the reliance on cars. Mixed-use development exemplifies the New Urbanist belief that neighborhoods should be designed for people, not just for cars or single-purpose buildings.

Community Focus

At the heart of New Urbanism is a strong focus on community, recognizing that vibrant public spaces are essential for fostering social interaction and a sense of belonging. Think of a charming town square where neighbors gather for a farmers’ market, children play in the park, and friends meet up for an outdoor concert. These universally accessible public spaces serve as the neighborhood’s living room, where people come together to share experiences, celebrate events, and build connections. This emphasis on community is a direct response to the isolating effects of suburban sprawl, where car-centric design often separates people from each other.

New Urbanism’s commitment to creating community-focused spaces is rooted in the belief that strong social ties are vital for a thriving, resilient neighborhood. By designing neighborhoods with inviting parks, squares, and community centers, New Urbanism encourages residents to engage with their surroundings and each other. These spaces become the heart and soul of the community, where people from all walks of life can come together, fostering a sense of unity and shared identity. This principle highlights the New Urbanist goal of creating neighborhoods that are not just places to live but places to belong.

Traditional Neighborhood Structure

New Urbanism advocates for a return to traditional neighborhood structure, where communities are designed with clear centers, edges, and a hierarchy of streets that naturally prioritize pedestrians. Imagine living in a neighborhood where everything you need—schools, shops, parks—is within a short walk or bike ride, and the streets are laid out in a way that makes sense, leading you naturally to the heart of the community. This approach to development patterns draws on the timeless principles of urban design that have been the foundation of great cities for centuries.

The traditional neighborhood structure is a key component of New Urbanism because it creates more cohesive and functional communities. By organizing neighborhoods around a central hub like a town square or main street and designing streets that prioritize pedestrians and cyclists instead of car-centric streets, New Urbanism seeks to create places that are both livable and accessible. This structure promotes social interaction, reduces traffic congestion, and makes neighborhoods more walkable and connected, aligning perfectly with the movement’s goal of fostering sustainable, human-centered urban environments.

Sustainable Infrastructure

Sustainability and care for the natural world are guiding principles of New Urbanism. Imagine living in a neighborhood where homes are energy-efficient, public transit is readily available, and abundant green spaces offer both beauty and environmental benefits like cleaner air and water. New Urbanism promotes sustainable practices at every level, from architecture and landscape design to the layout of entire neighborhoods, encouraging a lifestyle that minimizes environmental impact while enhancing quality of life.

The emphasis on sustainability within New Urbanism is driven by the understanding that the way we design our communities has a profound impact on the planet. By reducing reliance on cars, promoting energy-efficient buildings, and encouraging the use of public transportation and bicycles, New Urbanist communities are better equipped to handle the challenges of climate change and resource depletion. This principle underscores the movement’s vision of creating places that are not only beautiful and functional but also sustainable for future generations.

Quality Urban Design

Quality urban design is a hallmark of New Urbanism, where the focus is on creating functional, aesthetically pleasing spaces and enriching everyday life. Imagine walking through a neighborhood where every building, street, and public space is thoughtfully designed to create a harmonious and beautiful environment. This principle goes beyond mere architecture; it’s about crafting spaces that elevate the human experience, making residents feel proud to call their neighborhood home. Pioneers like Andrés Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, who were instrumental in the New Urbanism movement, emphasized the importance of designing with beauty and function in mind, recognizing that the built environment plays a crucial role in shaping our quality of life. Today, Ellen Dunham-Jones and June Williamson advocate for retrofitting suburbia in ways that support people and place.

New Urbanism’s commitment to quality urban design reflects the belief that beauty and functionality are not mutually exclusive but are instead complementary forces. Well-designed spaces foster a sense of well-being, encourage social interaction, and contribute to the overall sustainability of a community. When neighborhoods are visually appealing and thoughtfully laid out, they become places where people want to live, work, and play. This emphasis on quality urban design helps create vibrant, livable communities that resonate with the values of New Urbanism, where aesthetics and utility come together to enhance the everyday experience.

Diverse Housing Options

Diverse housing options are a key component of New Urbanism, ensuring that neighborhoods can accommodate people from all walks of life, regardless of their income level or stage in life. Imagine a community where single-family homes, apartments, townhouses, and affordable housing all coexist harmoniously, offering a range of choices to suit different needs and lifestyles. This diversity in housing fosters inclusivity and promotes economic and social sustainability, as it allows people to stay in the same community as their needs change over time. Visionaries like Peter Calthorpe, a leading figure in New Urbanism, have championed the idea of mixed-income neighborhoods as a way to create more equitable and resilient communities.

The principle of diverse housing options is central to New Urbanism’s vision of creating inclusive, thriving neighborhoods. By offering a variety of housing types and price points, New Urbanist communities can attract a broader range of residents, from young professionals to growing families and retirees. This diversity helps to build a more vibrant, dynamic community where people of different backgrounds and life stages can interact and support one another. It also reduces the pressure on the housing market, making it easier for people to find affordable, suitable homes within their preferred neighborhoods. In this way, diverse housing options are crucial to the New Urbanist goal of creating sustainable, inclusive, and resilient communities.

Integration with Natural Environments

Integration with nature is a fundamental principle of New Urbanism, which seeks to preserve and enhance natural landscapes within urban settings. Picture a neighborhood where parks, greenways, and natural areas are seamlessly woven into the urban fabric, providing residents with easy access to nature and its many benefits. This approach not only enhances the aesthetic appeal of a community but also promotes environmental sustainability by protecting natural ecosystems and providing green spaces that can help mitigate the effects of urbanization. Urban planners like Ian McHarg, whose work on ecological planning influenced the New Urbanism movement, emphasized the importance of designing with nature in mind to create healthier, more sustainable cities.

New Urbanism’s emphasis on integrating nature into urban environments reflects a deep understanding of the need for balance between the built and natural worlds. By preserving natural landscapes and incorporating green spaces into urban areas, New Urbanist communities offer residents the best of both worlds—access to the amenities and conveniences of city living and the restorative benefits of nature. This principle helps create healthier, more livable neighborhoods that are resilient to environmental challenges like climate change and provide residents with a higher quality of life. In this way, the integration of nature is central to New Urbanism’s vision of creating sustainable, harmonious communities.

Connectivity

Connectivity is a cornerstone of New Urbanism, focusing on the creation of well-connected street networks that make walking, biking, and public transportation more convenient and efficient. Imagine living in a neighborhood where every street is part of a well-thought-out grid, allowing you to easily navigate from your home to the local park, school, or grocery store without ever needing to get in a car. This emphasis on connectivity reduces traffic congestion and enhances the sense of community by making it easier for residents to interact and move about freely. The grid pattern, a favorite of New Urbanist planners like Leon Krier, has been a key tool in creating functional and friendly neighborhoods.

Fuel your creative fire & be a part of a supportive community that values how you love to live.

subscribe to our newsletter

*please check your Spam folder for the latest DesignDash Magazine issue immediately after subscription

New Urbanism’s focus on connectivity is about more than just efficient transportation; it’s about creating vibrant, dynamic communities where people feel connected to one another and their surroundings. A physically defined connected network encourages walking and biking reduces reliance on cars, and makes public transit a viable option for more people. This, in turn, leads to more sustainable, healthier neighborhoods where residents can enjoy a higher quality of life. Connectivity is essential to the New Urbanist vision of creating communities that are not only well-designed but also deeply connected—both physically and socially.

Smart Growth

Smart Growth is a concept closely aligned with New Urbanism, focusing on managing urban development environmentally and socially sustainably. Imagine a city where new development is concentrated in existing urban areas, revitalizing communities and reducing the need for sprawl. This approach protects open spaces and agricultural land and makes cities more livable by promoting walkability, reducing traffic, and encouraging public transportation. Smart Growth principles, championed by planners like Peter Calthorpe, emphasize the importance of thoughtful, deliberate growth that enhances the quality of life for all residents while minimizing the environmental impact.

New Urbanism’s adoption of Smart Growth principles is driven by the desire to create more sustainable, equitable communities. Smart Growth reduces urbanization’s environmental footprint while promoting social and economic sustainability by focusing on infill development and revitalizing existing neighborhoods. This approach helps create communities more resilient to climate change and economic fluctuations while providing residents with access to the amenities and opportunities they need to thrive. In this way, Smart Growth is integral to the New Urbanist vision of creating sustainable, livable cities that work for everyone.

Human Scale

Human scale is a guiding principle of New Urbanism, emphasizing the design of buildings and public spaces that are comfortable and inviting for people. This focus on the human scale is a response to the often overwhelming and impersonal nature of large-scale infrastructure like highways and massive parking lots, which can make cities feel inhospitable. New Urbanist thinkers like Léon Krier have long advocated for designing cities prioritizing the human experience, ensuring that spaces are scaled to the people using them.

The emphasis on human scale in New Urbanism reflects a deep commitment to creating livable, people-centered communities. By designing comfortable and inviting spaces, New Urbanist neighborhoods encourage social interaction, foster a sense of belonging, and enhance residents’ overall quality of life. This approach also helps to create more sustainable communities by promoting walkability and reducing the need for large, car-centric infrastructure. In short, human scale is about designing with people in mind, ensuring that neighborhoods are not just functional but also enjoyable places to live, work, and play.

Transit-Oriented Development (TOD)

Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) is a key strategy within New Urbanism, focusing on creating communities centered around accessible public transit hubs. Imagine living in a neighborhood where a quick walk takes you to a bus stop or train station that connects you to the rest of the city, reducing the need for car ownership and making your daily commute easier and more sustainable. TOD promotes the development of mixed-use neighborhoods near transit stations, ensuring that residents have easy access to public transportation, shops, schools, and parks. New Urbanist planners like Peter Calthorpe have been strong advocates for TOD, seeing it as a way to create more sustainable, livable cities.

New Urbanism’s embrace of Transit-Oriented Development reflects the movement’s commitment to creating communities that are both accessible and sustainable. By focusing development around transit hubs, TOD reduces the need for long car commutes, lowers traffic congestion, and promotes a more active, healthy lifestyle. It also supports the creation of vibrant, walkable neighborhoods where residents can easily access the amenities they need without relying on a car. In this way, TOD is an essential part of the New Urbanist vision of creating communities that are not only well-designed but also deeply connected and sustainable.

Urban-Rural Transect

The Urban-Rural Transect is a concept introduced by New Urbanists to describe the continuum of environments from urban centers to rural areas. Picture a city where the dense, vibrant urban core gradually gives way to quieter suburban neighborhoods, then to small towns, and finally to open countryside. This transect categorizes different zones, each with its own appropriate design and planning strategies, ensuring that development is suited to the context of each area. Andrés Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, key figures in the New Urbanism movement, developed the transect as a tool to guide the creation of more cohesive and context-sensitive communities.

New Urbanism’s use of the Urban-Rural Transect reflects a commitment to creating communities that are well-integrated into their surroundings and responsive to local conditions. By recognizing the different needs and characteristics of urban, suburban, and rural areas, the transect allows planners to design functional and sustainable neighborhoods. This approach helps preserve each area’s unique character while promoting more sustainable development patterns. The Urban-Rural Transect is a key tool in the New Urbanist toolkit, helping to create communities that are not only well-designed but also in harmony with their environment.

Form-Based Codes

Form-Based Codes are an innovative approach to zoning that emphasizes the physical form of buildings and their relationship to public spaces rather than just land use. Imagine a neighborhood where buildings are designed to complement each other and create a cohesive, attractive streetscape, with public spaces that invite people to gather and socialize. Unlike traditional zoning, which often focuses on separating different land uses, form-based codes prioritize the design and appearance of buildings, ensuring that new development enhances the overall character of the community. New Urbanists like Andrés Duany have been at the forefront of promoting form-based codes as a way to create more attractive, functional, and livable communities.

Community Participation

Community participation is a fundamental principle of New Urbanism, emphasizing the importance of involving locals in the planning and design process. Imagine living in a neighborhood where your voice is heard, where you have a say in how your community is developed and maintained. This participatory approach helps to ensure that developments meet the needs and desires of the people who live there, creating a stronger sense of ownership and pride among residents. New Urbanist planners like Andrés Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk have long advocated for community participation as a way to create more inclusive, responsive communities.

New Urbanism’s focus on community participation reflects the movement’s belief that the best communities are those that are built with input from the people who live there. By involving residents in the planning and design process, New Urbanist developments are more likely to meet the needs of the community, fostering a stronger sense of connection and engagement. This approach also helps to build trust and collaboration among residents, making neighborhoods more resilient and vibrant. Community participation is a key element of the New Urbanist vision of creating communities that are not only well-designed but also deeply connected and responsive to the needs of their residents.

The adoption of form-based codes within New Urbanism reflects the movement’s commitment to creating well-designed, cohesive neighborhoods. By focusing on the physical form of buildings and their relationship to public spaces, form-based codes help to ensure that new development fits seamlessly into the existing fabric of the community. This approach promotes a more human-centered, aesthetically pleasing urban environment, where buildings and public spaces work together to create a sense of place and identity. Form-based codes are an essential tool in the New Urbanist effort to create communities that are not just functional but also beautiful and enjoyable to live in.

Resilience

Resilience is a core principle of New Urbanism, emphasizing the need for communities to be adaptable and sustainable in the face of environmental, economic, and social challenges. Imagine living in a neighborhood designed to withstand climate change’s impacts, with energy-efficient buildings, green infrastructure, and a strong sense of community that helps residents support each other during difficult times. Resilience in New Urbanism is about more than just physical infrastructure; it’s about creating communities that can thrive in the long term, even in the face of uncertainty. New Urbanist thinkers like Douglas Farr have emphasized the importance of resilience as a key component of sustainable urban design.

New Urbanism’s focus on resilience reflects the movement’s commitment to creating communities that are prepared for the future. By incorporating sustainable practices and designing with flexibility in mind, New Urbanist neighborhoods are better equipped to handle the challenges of climate change, economic shifts, and social changes. This approach helps create livable, sustainable, thriving communities for generations to come. Resilience is at the heart of the New Urbanist vision of creating communities that are built to last, ensuring a high quality of life for all residents, now and in the future.

Place-Making

Place-making is a central tenet of New Urbanism, focusing on the creation of memorable, distinctive places that reflect local culture, history, and character. Imagine a neighborhood where every corner tells a story, with historic buildings preserved and repurposed, local materials used in new construction, and public spaces designed to foster a strong sense of community. Place-making focuses on creating spaces that resonate with people and make them feel connected to their community and proud of where they live. These spaces celebrate local history in an inclusive way. Jane Jacobs, whose ideas about vibrant, diverse urban spaces have deeply influenced New Urbanism, strongly advocated place-making to create more livable cities.

New Urbanism’s emphasis on place-making reflects the movement’s belief that communities should be more than just collections of buildings—they should be places where people feel a strong sense of belonging and identity. By focusing on a place’s unique character and history, New Urbanist developments create neighborhoods that are not only functional but rich in meaning and connection. This approach helps to foster a strong sense of community and pride among residents, making neighborhoods more resilient and vibrant. Place-making is a key component of the New Urbanist vision of creating communities that are not just places to live but places to thrive.

Join us for the focus & Flex challenge

Final Thoughts: Advocating for New Urbanist Principles in Your Community

You might think that your sprawling suburban neighborhood couldn’t possibly become a New Urbanist haven, but existing neighborhoods can absolutely be retrofitted to align with the principles. If you and your community advocate for it, you can turn your neighborhood into a more walkable, connected, and community-focused environment.

This process, often called “urban retrofitting” or “urban infill,” involves making strategic changes to infrastructure, zoning, and public spaces to better meet the needs of residents and encourage a more sustainable, human-centered way of living. Start by advocating for the addition of sidewalks, bike lanes, and public transit options. Push for mixed-use zoning that allows for a blend of residential, commercial, and recreational spaces. Supporting the creation of community spaces like parks, squares, and local markets that encourage social interaction and a strong sense of place.

Getting involved with local planning boards or neighborhood associations is a great first step for women who want to advocate for these changes in their communities. Building alliances with other residents, particularly those who share a vision for a more walkable and connected neighborhood, can amplify your voice.

Hosting community meetings, writing to local representatives, and using social media to raise awareness about the benefits of New Urbanist principles are also effective strategies. Educate yourself and others on the long-term benefits of these changes—like improved health, increased property values, and a stronger sense of community—to help garner broader support for retrofitting projects in your neighborhood.

We know you can make a difference!