From Gloomy to Glowing: How Elsie de Wolfe Undid the Victorian Parlor

Summary

Victorian interiors were built for a world of soot, gaslight, and privacy with heavy drapes, dark wallpapers, and densely layered objects that made homes feel like fortresses. As electricity, travel, and social roles shifted, so did the mood of interiors. Elsie de Wolfe didn’t strip rooms bare; she recast them. Her interiors were open, reflective, and theatrical in a different register with light bouncing off mirrors, treillage climbing walls, leopard print underfoot. She didn’t erase Victoriana. She helped it expand outward instead of inward.

Reflection Questions

How does the way a room is lit shape how we move through it — and how we feel inside it?

In what ways can historical design languages be edited, rather than erased, to speak to the present?

What does “maximalism” look like when it isn’t heavy — when it’s playful, airy, or social?

Journal Prompt

Think about a space you spend a lot of time in. If you approached it like Elsie de Wolfe — not stripping it back entirely but shifting its mood — what would you change? What would you keep? Write about how that transformation might feel, not just look.

If you step into a well-preserved Victorian drawing room, the first thing that greets you isn’t light. It’s atmosphere: dense, perfumed, and theatrical. Thick drapes fall over narrow windows, carpets silence every step, and the wallpaper does not so much decorate as envelop. This was not an accident. In the nineteenth century, rooms were meant to contain, not reveal.

As Rachel Davies writes in this article for Architectural Digest, “Rich fabric, voluminous drapes, lush upholstery, detailed woodwork, and inspiring rugs are all essential elements of Victorian design.” If you’re not a fan of Victorian design, you might think it looks quite caricaturish: tasselled pelmets, bric-à-brac, and more, more, more. If you love Victorian design, you might find it cozy and enveloping. But why were Victorian interiors so dark and heavy when their inhabitants valued the outdoors so greatly? And how did Elsie de Wolfe undo the darkness of 19th century design? Let’s explore.

Darkness Born of Necessity

Victorian interiors were not designed for sunlight; they were designed for survival in a world that was often dim and dirty. Gas lamps and candles cast a modest, flickering light that lent itself to shadow, not shine. In such rooms, pale plaster would have felt anaemic, washed out and unforgiving. Rich colors like burgundy, moss, tobacco brown didn’t just flatter the eye; they disguised the limits of technology.

This was an age of soot and smoke, of London fog that clung to coats and curtains alike. Heavy fabrics kept out draughts and filtered the grit. Tasselled pelmets framed windows like velvet prosceniums. Even in prosperous houses, there was an instinct to retreat from the world. Rooms were fortresses of civility, their crowded shelves and upholstered corners quietly declaring that this was a household untouched by the industrial grime beyond the front step.

Aesthetic Excess and the Cult of the Parlor

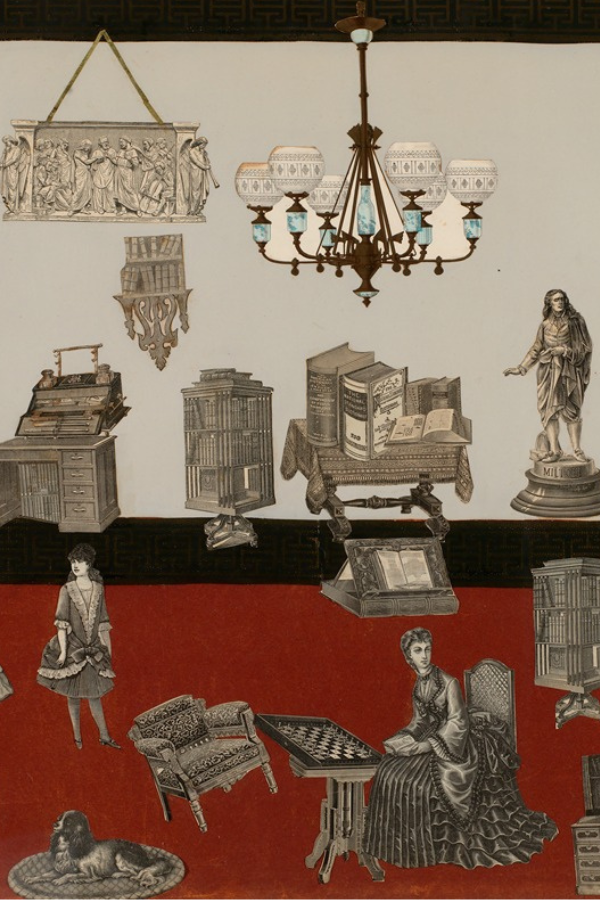

The Victorian parlor was quite unlike the modern living room. The parlor wasn’t a place to flop onto a sofa in your socks and curl up with a throw blanket. It was a stage. To the modern eye, its clutter can feel incredibly claustrophobic; every surface was claimed by a bibelot, every wall hung with portraits, landscapes, and faded bouquets of ribbon. But in its own time, this visual noise was the language of taste. More was more.

A well-to-do home was expected to demonstrate its cultural capital in the parlour. It was here that visitors formed their first impressions, where family heirlooms mingled with mass-produced ornament, and where every tassel and figurine testified to a certain standing. Privacy was a performance, and interiors carried it off with velvet aplomb.

Cultural Shifts and a Changing Light

By the last years of the nineteenth century, the world outside these thickly curtained rooms had already begun to move on. Gaslight was being overtaken by electricity, bringing with it a cleaner, more revealing glow. Heavy drapery no longer softened the light; it blocked it. What had once been a comfort (shadowy corners, plush upholstery, a palette of russet and green) started to feel oppressive.

There was also a cultural shift. Travel was easier, and people returned from the Continent with different ideas about how rooms should look and feel. Hotels in Paris and the Riviera were light, bright, and unapologetically open. The outside world no longer seemed quite so threatening, and the parlor’s sense of enforced seclusion began to look outdated.

Women, too, were moving differently through society. They were working, gathering, and socializing in ways their mothers hadn’t. Domestic interiors, once intended to shut the world out, were suddenly expected to let a little of it in.

Elsie de Wolfe Draws Back the Curtains

Who better to step in and seize the moment than Elsie de Wolfe? An actress before she became a decorator, she understood the power of atmosphere better than most. Where the Victorians layered fabrics, she removed them. Where they favored flock wallpaper and mahogany, she reached for pale paint, mirrors, and painted furniture.

Her most famous project, the Colony Club in New York in 1905, made the point perfectly. Instead of the suffocating gloom of a late Victorian drawing room, the club offered rooms that were airy, pale, and elegantly restrained. Furniture was scaled for conversation, not intimidation. Walls reflected light rather than swallowing it. The result felt revolutionary, though the ingredients were simple: fresh paint, lighter fabrics, more air.

Elsie de Wolfe changed the mood inside our interiors. She understood that interiors didn’t have to be grand to be beautiful; they just had to feel alive. Victorian interiors were dense, dark, and inward-facing. Elsie de Wolfe’s interiors were equally performative, but open, reflective, and social. She replaced the gloom with glamour. Not less decoration… just lighter, glossier, more theatrical.

Taking a Softer Step Into Modernity

Her approach was modern, but it wasn’t austere. She didn’t reject history; she edited it.

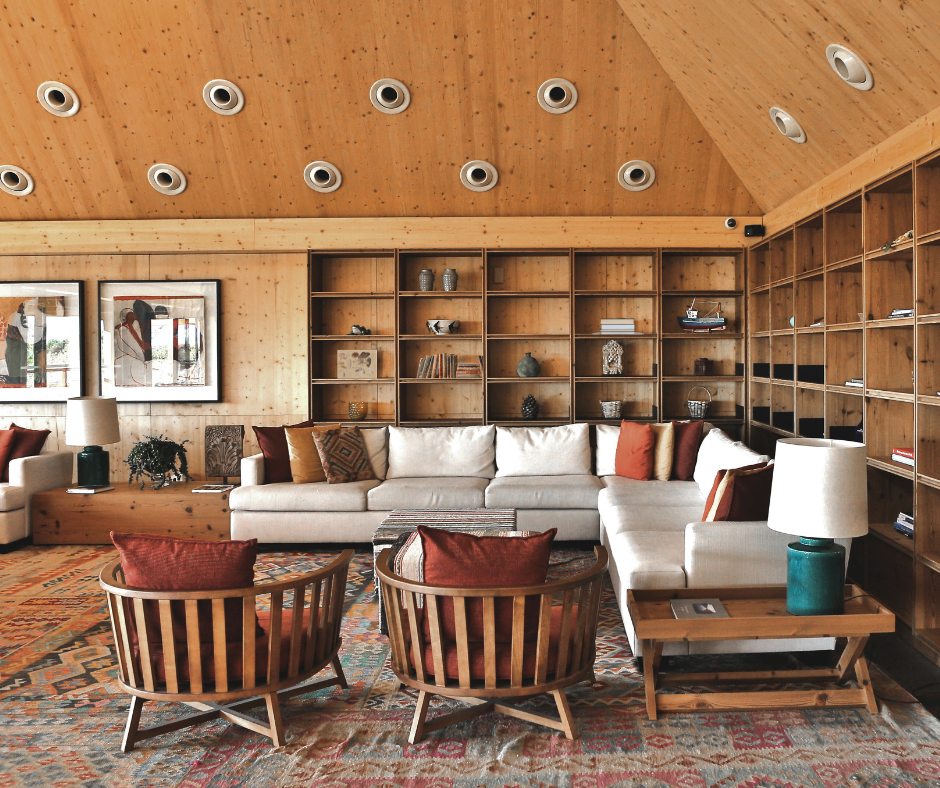

Elsie de Wolfe is often flattened into shorthand for “light and airy,” but the reality is a bit more complicated, and, frankly, more interesting. Her interiors were not minimal. They were layered, theatrical, and absolutely intentional, just in a way that felt different from Victorian heaviness. She loved mirrored walls, chinoiserie, striped silk, treillage, painted furniture, Louis XVI chairs, white slipcovers, leopard print (famously), and entire rooms glazed in pale colors with gilded edges. None of that is restrained in the modern sense.Her interiors were neither stark nor sentimental, just lighter.

Fuel your creative fire & be a part of a supportive community that values how you love to live.

subscribe to our newsletter

*please check your Spam folder for the latest DesignDash Magazine issue immediately after subscription

And they set the tone for the decades that followed. Pale walls, mirrored panels, painted furniture, floral chintz; these became the language of the early twentieth-century interior. They were bold and beautiful and energetic in their own ways, but they also rebelled against a century of excess.

Honoring the Victorian Interior without the Weight of What Came Before

It would be unfair, though, to pretend that Victorian interiors were without merit. Their material richness of carved wood, intricate tiles, and William Morris patterns has enduring appeal due to its craftsmanship and care. Designers still mine the period for ideas, often taking its decorative vocabulary and paring it back.

This is what makes the period so enduring. Its darkness can be softened. Its clutter can be combed through and refined. What Elsie de Wolfe offered wasn’t a repudiation of the past but a way of empowering it to adapt.

Enjoy These DesignDash Articles About Victorian Interior Design

Written by the DesignDash Editorial Team

Our contributors include experienced designers, firm owners, design writers, and other industry professionals. If you’re interested in submitting your work or collaborating, please reach out to our Editor-in-Chief at editor@designdash.com.