Who Was Hans Wegner and Why Does His Work Still Matter?

Summary

Hans J. Wegner built his reputation by returning to the same problem again and again: how to make a chair that works, lasts, and feels right. Trained as a cabinetmaker, he approached modernism through craft rather than theory, favoring wood, clear structure, and careful proportion. His most famous designs, including the Round Chair and the Wishbone Chair, became widely adopted not because they chased novelty, but because they balanced comfort, restraint, and use with unusual consistency. Decades later, his work still circulates easily between homes, museums, and production floors, which explains why it continues to matter.

Reflection Questions

Wegner spent much of his career refining variations of the same object. Where in your own work might repetition, rather than expansion, lead to stronger results?

Wegner kept design closely tied to making. How directly connected are you to the materials, processes, or people who produce your work, and what might change if that connection were closer?

Many of Wegner’s most successful designs avoid visual emphasis and rely instead on use and proportion. How do you currently decide when a design is finished, and what signals do you trust most?

Journal Prompt

Think about a piece of work you return to often, or a problem you keep circling back to. Write about why it continues to hold your attention. What parts of it still feel unresolved? What would it look like to stay with that problem longer, rather than moving on to something new?

Hans J. Wegner was (and still is) an icon of twentieth-century design. His work sits comfortably inside modernism, yet never leans on shock or provocation. Instead, it insists on use, craft, and proportion. And chairs, above all else, chairs. Over a lifetime, Wegner designed hundreds of them, refining a narrow typology with incredible patience. Some are formal, others relaxed. A few are playful. All are Hans Wegner and all are entirely deliberate.

When Wegner died in Copenhagen in January 2007 at the age of 92, the New York Times described him as a designer who helped soften modernism’s harder edges to make room for comfort without losing the discipline he was known for (New York Times, 2007). Comfort was central to Wegner’s particular kind of modernism: not the chilly, machine-age romance of chrome and glass, but a modernism domesticated by warm materials, the body’s needs, and the cabinetmaker’s hand.

Nearly 20 years after his death, designers continue to draw from his furniture collections as they craft their own. Read on to learn more about Wegner and his impressive career.

Wegner Began His Decades-Long Career at Age 14

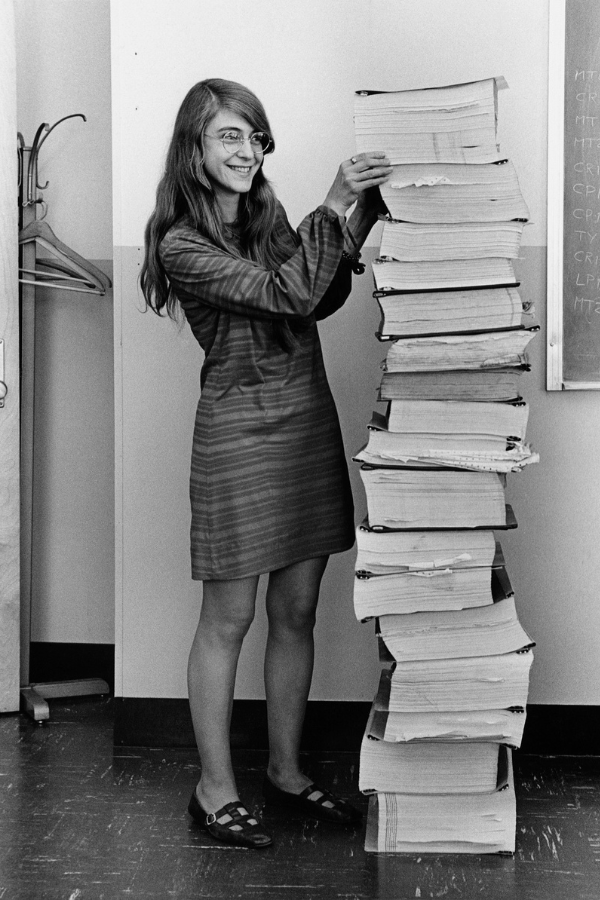

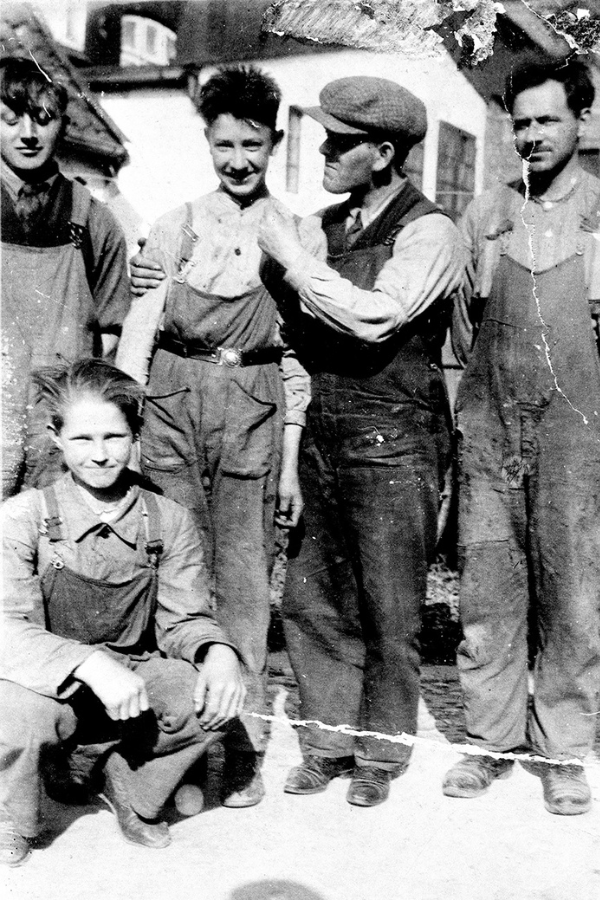

Wegner was born in 1914 in Tønder, a small town in southern Denmark. His father was a cobbler, and the household placed value on skilled handwork. Wood entered his life early. As a teenager (pictured above third person from the left), he apprenticed with master cabinetmaker H. F. Stahlberg, completing a traditional training that emphasized joinery, surface, and structural logic. This was not an abstract education. It involved tools, deadlines, mistakes, and correction. The habits formed there stayed with him throughout his entire career.

Early training and the habits of craft

In the mid to late 1930s, Wegner moved to Copenhagen to continue his education and to find work. He studied at the School of Arts and Crafts and absorbed the functionalist thinking circulating among Danish architects at the time. There, he surpassed his cabinet design capacities, turning attention to tables, desks, chairs, cushions, and even lighting. He also paid close attention to how furniture moved from drawing to workshop. That interest in production, not just form, shaped his career. He did not imagine furniture apart from the people who would build it.

This is one reason Wegner never quite fit the stereotype of the lone “genius designer” sketching forms for anonymous factories. Even at the height of his fame, others noticed a cabinetmaker’s temperament in him. In the Times obituary, Paola Antonelli, MoMA’s curator of architecture and design, called him “one of … the humble giants of 20th-century design,” someone who would likely “shun the term designer and prefer to call themselves cabinetmakers.”

That line is memorable because it points to a real tension in the 20th century between design as image-making and design as making-making. Wegner (especially in his early and middle years) stood firmly on the making side.

Aarhus and early professional work

In 1938, while still completing his studies, Wegner was hired by architects Arne Jacobsen and Erik Møller to design furniture for the new Aarhus City Hall. Later, he would also work alongside Andreas Tuck and Erik Jørgensen, but he would not develop a deep, decades-long partnership with Erik in the way he did with Hansen or Møbler. Back to 1938: this was the same year that he made his debut at the Copenhagen Cabinetmakers’ Guild exhibition. The Guild exhibitions were crucial as they created a public stage where architects, designers, and master cabinetmakers could treat furniture as serious culture, not mere domestic equipment.

Developing alongside Jacobsen and Møller was an early opportunity to work at an architectural scale and under real-world constraints. World War II delayed construction, but Wegner remained involved, designing interiors and fittings across several public projects in the region.

This period also marked the start of his long association with skilled cabinetmakers. Johannes Hansen, in particular, became central to Wegner’s development. Their collaboration produced work that balanced experimentation with discipline. The annual Copenhagen Cabinetmakers’ Guild exhibitions provided a setting where such partnerships mattered. Furniture was judged publicly, by peers and press, not hidden behind marketing claims.

Wegner also built a family life alongside that work. He married Inga Helbo in 1940. Family life and work were closely linked from then on. According to his daughter Marianne, furniture was his primary focus. Vacations took persuasion. Still, his practice was braided into family and daily routine; “Working out of a studio at his house,” the obituary observes, he produced “hundreds of prototypes” and needed to be pressed to leave work for vacations.

Chairs and the problem of refinement

By the mid-1940s, Wegner had begun concentrating on chairs almost exclusively. This was not accidental. Chairs pose difficult questions for designers to answer. They must support the body, look convincing from every angle, and tolerate daily use. There is little room for excess. Wegner returned to this problem repeatedly. To solve it, Wegner created The Peacock Chair, The Folding Chair, The Papa Bear Chair, The Chinese Chair, The Flag Halyard Chair, The Ox Chair, and so many others.

In 1949, two chairs introduced that year shaped his reputation internationally. One was the Round Chair, often referred to simply as “The Chair.” It combined armrest and back into a single curved rail, supported by slender legs and a woven seat. When Richard Nixon and John F. Kennedy sat in this chair during the first televised U.S. presidential debate in 1960, it gained a level of exposure few furniture designs ever receive (New York Times, 2007). The chair looked modern without feeling aggressive as some of the more industrialist designs did.

That same year, Wegner completed the CH24, now widely known as the Wishbone Chair. Produced by Carl Hansen & Søn since 1950, it has never left production. The chair draws loosely on Chinese seating forms, filtered through Danish construction methods and proportions. The Y-shaped back splat gives the chair its nickname, but the real achievement lies in the balance Wegner achieved with this piece.

Wegner honored tradition and history despite his interest in modernism. Even in his most modern work, Wegner wasn’t trying to sever ties with older chair traditions. Instead, he treated traditional chair forms as problems to be re-solved, stripped down, rebalanced, purified.

America, attention, and restraint

By the early 1950s, Danish Modern furniture found a receptive audience in the United States and abroad. He was honored repeatedly for his modern designs and thought leadership; for example, he was selected as Honorary Royal Designer of the Royal Society of Arts in London.

Wegner was part of a group that included Arne Jacobsen, Finn Juhl, and Børge Mogensen. Their work appealed to American architects, editors, and collectors who wanted modern furniture that felt livable. Danish Modern, in particular, provided an appealing alternative to the Bauhaus-influenced International Style: less metallic, less architectural, more intimate. Wood replaced chrome. Upholstery softened profiles.

Wegner visited the United States in the early 1950s and observed American industrial production firsthand. He declined offers to relocate or license his work for mass manufacturing there. The scale and speed did not interest him. He preferred the Danish model, where production remained close to the designer and changes could be controlled.

Museums took note. The Museum of Modern Art in New York acquired several of his chairs, including the Folding Chair from 1949. These acquisitions framed Wegner as part of an international modern canon, even as he continued working quietly through Danish workshops. Wegner also entered popular culture by way of politics, as shown at the nationally televised U.S. presidential debate in 1960. The Times notes that Vice President Richard Nixon and Senator John F. Kennedy were seated on Wegner chairs.

Industry relationships and Knoll

In 1969, Knoll acquired exclusive U.S. distribution rights for a group of Wegner designs manufactured by Johannes Hansen. The Knoll Wegner Collection included more than a dozen chairs and a cabinet system. Knoll described the acquisition as part of its commitment to preserving and promoting modern furniture design, positioning Wegner alongside other established figures of twentieth-century modernism.

Fuel your creative fire & be a part of a supportive community that values how you love to live.

subscribe to our newsletter

*please check your Spam folder for the latest DesignDash Magazine issue immediately after subscription

That word—preservation—is key. Wegner’s furniture lives in a unique space where it is simultaneously heritage and product, museum object and daily tool. Some designers become collectible after their working life ends; Wegner became collectible while still being manufacturable.

This moment coincided with a broader decline in American interest in Danish Modern furniture. Tastes shifted. Plastic, bright color, and novelty gained ground. Wegner continued working, though the market was less receptive. He focused on smaller-scale production and deeper collaboration with select manufacturers, particularly PP Møbler, where experimental work and limited runs were possible.

Working methods and design thinking

Many designers are remembered for a look. Wegner is remembered for a stance: a conviction that furniture should reveal how it is made, and that simplicity is not a style but a discipline. Carl Hansen & Søn frames the “core” of his legacy as showing “the inner soul of furniture pieces through a simple and functional exterior,” grounded in deep knowledge of joinery and deep respect for wood’s potential.

Wegner’s furniture reveals a consistent way of thinking. He favored wood and traditional construction methods. Mortise-and-tenon joints, sculpted armrests, and woven seats appear again and again. These choices were not nostalgic. They solved practical problems and communicated structure clearly.

As detailed by the same Carl Hansen article, Wegner himself described the Danish style not as a sudden invention but as a long refinement: “a continuous process of purification and simplification – to cut down to the simplest possible design of four legs, a seat, and a combined back- and armrest.”

He often revisited earlier designs, adjusting dimensions, angles, and joints. Critics have noted how motifs travel across his work. Curved back rails migrate from one chair to another. Armrest profiles evolve. The changes can be subtle. That was the point. Wegner believed improvement came from small adjustments rather than dramatic gestures.

He once remarked that designing even one good chair would be enough for a lifetime.

Later years and renewed interest

Wegner continued designing into the late 1980s. The Times obituary paints Wegner as a man with few distractions beyond furniture. But in the early 1990s, declining health led him to step back from daily work. His daughter Marianne took over the studio.

By then, interest in mid-century furniture was returning, driven by collectors, museums, and a new generation of designers looking backward with fresh eyes. This late-life revival matters emotionally as well as historically. Many designers live long enough to see their work become dated; fewer live long enough to watch it become newly desired, newly understood.

The renewed attention was not abstract. Demand increased for original Wegner designs, both vintage and newly produced. The Wishbone Chair, the Round Chair, and others entered a broader cultural conversation about quality, longevity, and domestic life. Wegner lived long enough to see this return but he did not comment much on it.

He died in 2007 in Copenhagen. His obituary in the New York Times noted that what once felt fashionable had settled into something more stable. Furniture designed half a century earlier now occupied dining rooms, offices, and public buildings without explanation (New York Times, 2007).

Why Wegner’s Work Still Matters

What endures about Hans J. Wegner is not only the silhouettes (though those are extraordinary), but the ethic embodied in them. His chairs suggest that comfort and elegance are not opposites; that a joint can be both honest and beautiful; that tradition can be a resource rather than a constraint. Even today, in an era of rapid product cycles and disposable furnishings, Wegner’s work encourages us to make fewer things, make them better, and let the human body (not fashion) be the final judge.

Still in continuous production today, Wegner’s chairs circulate between homes, museums, and manufacturers’ catalogs. They are photographed often and discussed constantly. Yet their success still depends on the same thing it always did. You sit down. You stay awhile. You return again and again.

Chairs in the featured image:

- 1960s Mid-Century Modern Hans Wegner Peacock Chair on 1stDibs

- The Ox Chair designed by Hans Wegner, on Modernica

- Hans Wegner Round Chair on Rove Concepts

- Carl Hansen & Søn CH20 Elbow Chair by Hans Wegner on DWR

- Carl Hansen & Søn Shell Chair by Hans Wegner on DWR

Written by the DesignDash Editorial Team

Our contributors include experienced designers, firm owners, design writers, and other industry professionals. If you’re interested in submitting your work or collaborating, please reach out to our Editor-in-Chief at editor@designdash.com.