Examining the Centuries’ Long Fight for Women’s Property Rights in America

Summary

This article delves into the historical evolution of women’s rights to own property in the U.S., spotlighting the legal and societal barriers they faced and overcame. It traces the journey from coverture laws, which severely restricted women’s property rights, through to significant legislative reforms like the Married Women’s Property Acts and the Equal Credit Opportunity Act of 1974, highlighting the intersectional struggles faced by women of color and immigrant women.

Reflection Questions

- How have historical property rights for women impacted gender equality in modern times?

- In what ways do the struggles of women of color and immigrant women for property rights differ from those of white women?

- Consider the role of legislation like the Equal Credit Opportunity Act of 1974 in advancing women’s rights. Why are such laws significant?

Journal Prompt

Reflect on the evolution of women’s property rights in America. Write about how understanding this history can inform current efforts to ensure equal rights for all women, considering the ongoing challenges faced by marginalized groups.

This month, we’re focusing on women—like always! But because it’s Women’s History Month, we’re paying particularly close attention to defining moments of the past. Today, let’s take a look at how women’s property rights have evolved in our country. In 2024, single women in the U.S. own more houses than single men do. A LendingTree analysis of the latest U.S. Census Bureau data revealed that single women own 2.71 million more homes than single men. Specifically, single women own 10.95 million homes, while single men own 8.24 million. Single women, on average, own 12.93% of the owner-occupied homes across the 50 states, compared to 10.22% among single men.

Of course, this wasn’t always the case. The history of women’s property rights in the United States reflects a long and evolving struggle for equality. Initially, women’s rights to own, manage, and dispose of property were severely limited by laws and societal norms. It wasn’t until the Equal Credit Opportunity Act of 1974 that women’s rights to own and manage property regardless of their marital status were truly solidified by federal law. Let’s look back in time at how these rights have changed, while we reinforce how important it is to reflect on women’s history.

An Abridged History of Female Property Rights in America

In the United States, certain men could always own property—but not women. The history of women’s property rights in the United States reflects a long and evolving struggle for equality. Initially, women’s rights to own, manage, and dispose of property were severely limited.

Let’s say that U.S. history began with the first permanent English settlement in 1607. The period from the first permanent English settlement in Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607, to 1974, when women gained completely equal rights to own property as men, spans 367 years. This means that women did not have the same rights as men to inherit, own, and sell property for approximately 88% of American history from 1607 up to our current year (2024), based on a total duration of 417 years. It took 367 years for women to enjoy the same property rights as men in the United States.

The evolution of these rights can be divided into several key periods. Let’s take a closer look.

Fuel your creative fire & be a part of a supportive community that values how you love to live.

subscribe to our newsletter

*please check your Spam folder for the latest DesignDash Magazine issue immediately after subscription

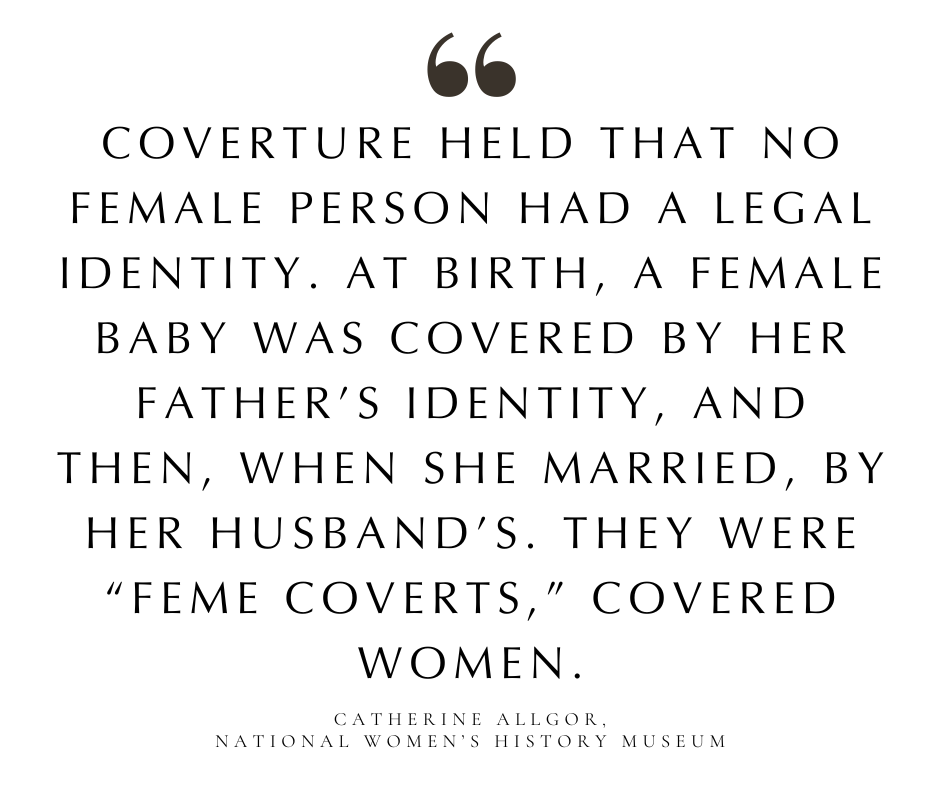

Coverture in Colonial America

Throughout much of the Colonial period, both single and married women’s property rights were practically non-existent. The concept of coverture, deeply ingrained in the colonial era and early 19th century American legal system, originated from English common law. It was a legal doctrine that significantly affected the lives of each married woman, dictating their legal status and rights, particularly concerning property ownership, contracts, and legal actions. As Catherine Allgor writes in this article about coverture published by the National Women’s History Museum, “Because they did not legally exist, married women could not make contracts or be sued, so they could not own or work in businesses. Married women owned nothing, not even the clothes on their backs.”

The Legal Foundation of Coverture

Coverture held that upon marriage, a woman’s legal identity was consolidated with that of her husband. Essentially, the law saw the husband and wife as one person, and that person was the husband. This concept meant that a married woman, referred to as a feme covert, could not own property, enter into contracts, or engage in legal proceedings in her own name.

Any property a woman brought into a marriage or acquired during the marriage automatically became controlled by her husband. He had the right to manage and benefit from it, though certain restrictions were placed on his ability to sell or transfer real estate without her consent.

Its Impact on Women

Coverture created a system of legal and economic dependence of wives on their husbands. Women had limited ability to protect their interests or assert autonomy, reinforcing societal norms that dictated a woman’s place was under her husband’s authority.

Unmarried women (spinsters) and widows (femes sole) had more legal autonomy to sole and separate property, including the right to own property, enter contracts, and take legal action. However, these rights were often limited by societal norms and other legal restrictions, reflecting the broader view of women’s subordinate status.

Resistance and Reform to Coverture: The Married Women’s Property Acts

The restrictions imposed by coverture were not universally accepted, and over time, they faced criticism from various quarters. Advocates for women’s rights, including early feminists and legal reformers, began to challenge these laws and the principles behind them. The push for change eventually led to legal reforms, starting with the Married Women’s Property Acts passed in various states beginning in the 1830s. These changes to Colonial property laws were significant.

The first Married Women’s Property Act was passed in New York in 1848, inspired by the growing women’s rights movement and the recognition of the injustices imposed by coverture. It finally acknowledged the legal existence of women.

Other states soon followed, each drafting their versions of the law. While the specifics varied, the acts generally allowed married women to own property in their own name and on their own behalf, inherit money and property directly, engage in contracts, retain earnings, sue and be sued, and engage in legal proceedings. Some laws also addressed the issue of a woman’s right to her earnings and the custody of her children, giving married women substantial control of their own lives.

Women Who Fought to Abolish Coverture

Overturning the legal doctrine of coverture in the United States was a gradual process that involved the efforts of many women (and men) who advocated for women’s rights and legal reform. While there were no single individuals responsible for overturning coverture, several notable women played significant roles in advocating for the legal changes that ultimately led to the erosion of coverture laws. These women were often also involved in broader movements for women’s suffrage, property rights, and social reform.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

A leading figure in the early women’s rights movement, Stanton was instrumental in organizing the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848, which issued the Declaration of Sentiments calling for equal social, political, and legal rights for women. Stanton’s advocacy included a push for women’s property rights and the reform of marriage laws.

Susan B. Anthony

While best known for her work in the women’s suffrage movement, Anthony also advocated for married women’s property rights. She worked closely with Stanton and others to challenge laws that discriminated against women, including those related to property and economic independence.

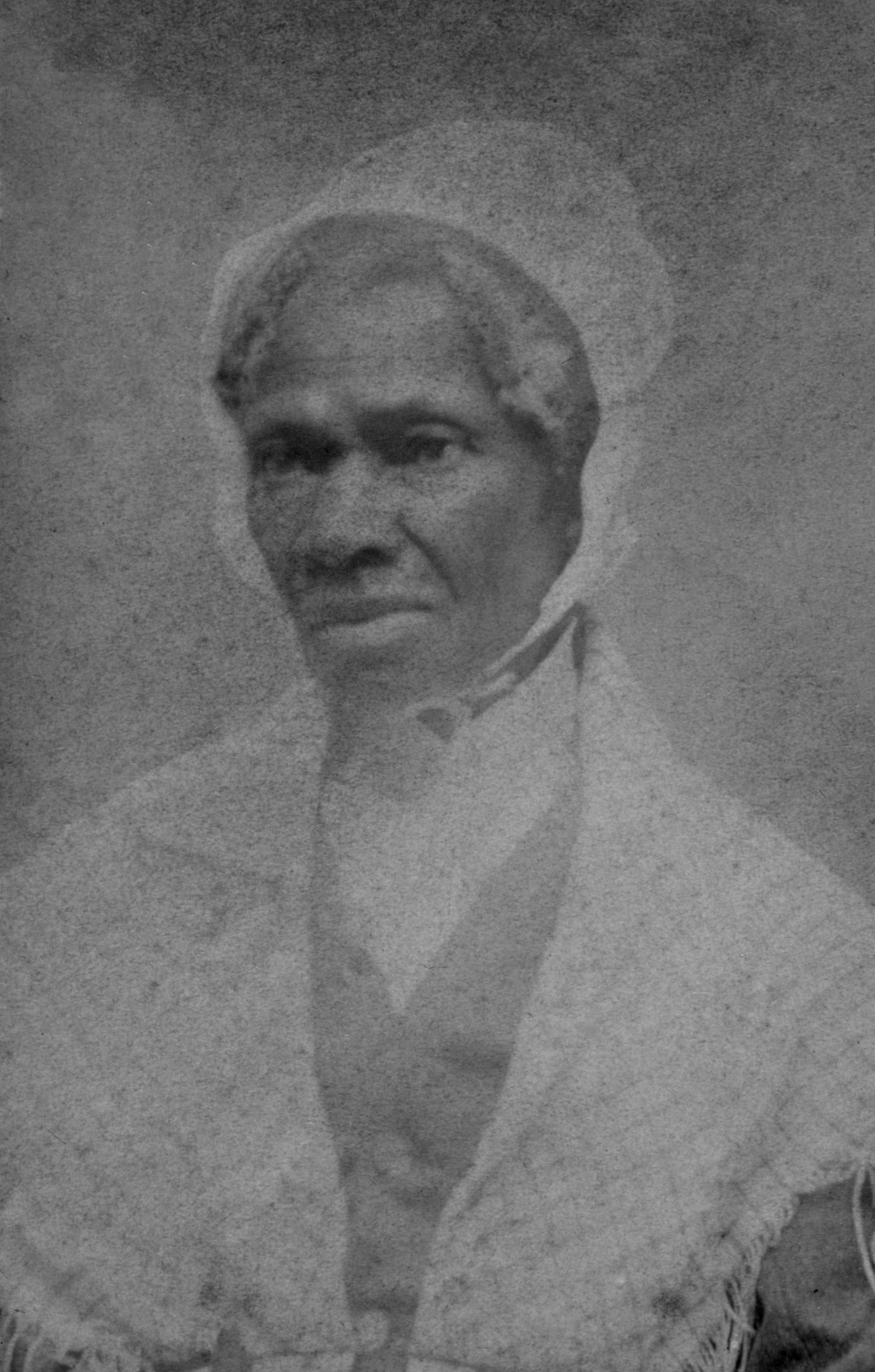

Sojourner Truth

Women of color, including Sojourner Truth, also advocated for women’s rights, including property rights, while simultaneously fighting against slavery and racial discrimination. Their contributions were vital in linking the struggles for racial equality with gender equality, although their work is often less recognized in historical accounts.

Lucy Stone

An ardent abolitionist and suffragist, Stone also advocated for changes in the laws governing women’s rights to property. She was a key figure in the early women’s movement and helped to bring attention to the issues of coverture and economic independence for women.

Myra Bradwell

Bradwell was an early female lawyer in the United States who challenged the Supreme Court for her right to practice law in the case Bradwell v. Illinois (1873). Although she lost her case, Bradwell’s efforts highlighted the legal disabilities imposed on women by coverture and contributed to the dialogue around women’s legal rights.

Impact, Limitations, and Broader Implications of the Married Women’s Property Law

These acts were revolutionary because they acknowledged married women as legal entities separate from their husbands, capable of owning property and conducting business in their own right. They laid the foundation for further reforms in women’s legal rights.

The impact of the Married Women’s Property Acts varied widely across states due to differences in the scope and implementation of the laws. Additionally, societal norms and the reluctance of some legal systems to fully enforce these laws meant that many women did not fully experience their potential benefits. Despite these acts, women still faced significant legal and social barriers to complete economic and legal independence.

By allowing women to own and manage property, these acts contributed to a slow but significant transformation in societal views about women’s roles and capabilities, both within the family and in society at large. The enactment and spread of Married Women’s Property Acts were closely linked to the broader women’s rights movement, including the push for suffrage. These legal changes helped to mobilize support for further reforms and highlighted the inconsistency between women’s legal status and the ideal of equal citizenship.

Women’s Suffrage and Property Rights in the Early 20th Century

The early 20th century marked a pivotal era in the history of women’s rights in the United States, culminating in the ratification of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1920. This period saw significant advancements in the recognition of women’s rights, including their economic rights, but also highlighted the ongoing challenges and restrictions that continued to limit women’s full participation in economic life.

The 19th Amendment

Led in large part by the National Woman Suffrage Association, the movement for women’s right to vote in the United States gained momentum in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as activists lobbied, protested, and campaigned for the right to vote. This effort was part of a broader struggle for women’s rights, including access to education, employment opportunities, and legal rights.

After decades of advocacy and activism, the 19th Amendment was ratified on August 18, 1920. It stated, “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” This landmark amendment enfranchised women, acknowledging their right to participate fully in the democratic process.

The 19th Amendment’s Impact on Economic Rights

The 19th Amendment was a significant victory for women’s rights, symbolizing their recognition as full citizens. It also had practical implications for women’s economic rights, as the ability to vote enabled women to influence public policy, including laws related to property ownership, employment, and financial independence.

Despite the ratification of the 19th Amendment, many women, particularly married women, continued to face legal and societal restrictions on their economic rights. State laws and societal norms still limited women’s ability to own property, control their finances, and engage in business independently of their husbands.

Persistent Challenges and Further Reforms in the Mid-to-Late 20th Century

While Married Women’s Property Acts had been enacted in various states throughout the 19th century, their implementation and impact were uneven. Many married women still encountered legal obstacles to owning property and managing their finances independently.

Women faced widespread discrimination in the workforce, including lower wages than men for the same work, limited access to certain professions, and barriers to advancing in their careers. Legal protections against such discrimination were minimal or non-existent at this time.

The struggle for economic rights continued beyond the ratification of the 19th Amendment. The mid-20th century saw further legal reforms aimed at addressing gender discrimination, including the Equal Pay Act of 1963 and the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which included provisions against employment discrimination based on sex. The Women’s Liberation Movement of the 1960s and 1970s also played a crucial role in advocating for women’s economic, legal, and social rights.

The Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA) of 1974

The Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA) of 1974 is a landmark federal law in the United States designed to ensure that all consumers have an equal chance to obtain credit. This was a significant step forward in the fight against discrimination in the lending process, directly impacting women’s ability to own property and manage their finances independently. Before the ECOA, women, especially unmarried women and widows, often faced significant barriers when attempting to obtain credit or loans, due in part to discriminatory practices by lenders.

Key Provisions of the ECOA

The ECOA makes it illegal for creditors to discriminate against applicants on the basis of race, color, religion, national origin, sex, marital status, age (provided the applicant has the capacity to enter into a binding contract), because all or part of the applicant’s income derives from any public assistance program, or because the applicant has in good faith exercised any right under the Consumer Credit Protection Act.

Creditors are required to consider individual creditworthiness, not based on stereotypes or assumptions related to these protected characteristics. For women, this meant that their own income, assets, and credit history had to be considered separately from their husbands’ if they applied for credit in their own name.

Creditors must inform applicants of the decision on their credit application or request within 30 days. If an application is denied, creditors must provide a written notice that includes the specific reasons for the denial or informs the applicant of their right to learn the reasons if they ask within 60 days.

The ECOA’s Impact on Women

By making it easier for women to obtain credit, the ECOA played a crucial role in enabling women to purchase homes, start businesses, and manage their finances independently of their husbands or male relatives. This was a significant step toward financial equality, as it allowed women to build credit in their own names and make financial decisions without male co-signers.

The act contributed to the broader economic empowerment of women by opening up opportunities for entrepreneurship and property ownership, key components of financial stability and wealth building. It has been amended and expanded over the years to further its reach and effectiveness in preventing credit discrimination.

How Women in America Fought for the Right to Own Property

Women in America have used various strategies and methods to lobby for their rights to inherit, purchase, and sell real and personal property, reflecting a broader struggle for gender equality. These efforts were characterized by both collective action and individual advocacy, involving a mix of legal challenges, political lobbying, grassroots activism, and public campaigning. The journey to secure property rights for women was intertwined with other social and political movements, including the suffrage movement, which sought to secure voting rights for women.

Some women challenged discriminatory laws directly in court, leading to landmark cases that gradually changed legal interpretations and precedents regarding women’s rights. Many women organized or joined women’s clubs and societies, which became platforms for advocating for various rights, including property rights. These groups often held meetings, circulated petitions, and lobbied lawmakers. Women activists gave speeches, wrote articles, and published pamphlets that argued for women’s property rights, making the case that these rights were essential for women’s independence and economic security.

Of course, we must note that not all women in America endured the same struggles while trying to expand their limited property rights. While advocating for their rights, black women, other women of color, and immigrant women faced additional barriers due to racial and ethnic discrimination. Organizations like the National Association of Colored Women (NACW) addressed issues specific to women of color, including property rights.

Property Rights of Immigrant Women and Women of Color in the United States

We cannot have this discussion without acknowledging how differently the property rights of women of color and immigrant women evolved than those of white, U.S.-born women. The history of property rights for Black women, other women of color, and immigrant women in the United States is complex and distinct in many respects from the general progression of women’s property rights. These differences stem from the intersections of race, ethnicity, and legal status, which have historically influenced and often constrained their rights and opportunities in unique ways.

For all these groups, the fight for property rights has been deeply intertwined with broader struggles for civil rights, economic justice, and an end to racial and gender discrimination. While legislative changes have provided formal equality in many respects, systemic inequities and historical legacies continue to affect the ability of Black women, women of color, and immigrant women to fully exercise their property rights and achieve economic parity.

Black Women’s Property Rights

From the early 17th century until all states acknowledged emancipation, enslaved Black people were legally considered property rather than persons with rights, including any children they bore. This denied them not only personal autonomy but also the ability to own property.

Following the Civil War and emancipation, Black people, including women, gained formal legal status, including the right to own property. However, systemic racism, Jim Crow laws in the South, and discriminatory practices nationwide severely limited their ability to exercise these rights.

The civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s was crucial in challenging systemic discrimination. Laws such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Fair Housing Act of 1968 aimed to eliminate discrimination in voting, employment, and housing. However, systemic barriers and the legacy of discrimination have continued to impact Black women’s property ownership and economic opportunities.

Property Rights of Indigenous Women in America

Indigenous women in the U.S. faced their own unique challenges regarding property rights, heavily influenced by U.S. policies towards Native American lands. The Dawes Act of 1887, for example, aimed to assimilate Native Americans into American society by allotting land to individual owners, disrupting traditional communal land ownership. Over time, policies shifted, but the legacy of these actions has had long-lasting effects on property ownership and rights among Native American communities.

Property Rights of Asian and Latina Women in America

Immigration laws and policies have significantly impacted property rights for Asian and Latina women. Exclusionary laws in the 19th and early 20th centuries, like the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and the Immigration Act of 1924, not only restricted immigration from Asia but also limited the rights of immigrants to own property.

Latina women, particularly those in territories annexed by the U.S., such as Puerto Rico, faced challenges in maintaining property rights during and after the transition to U.S. governance. Over time, as immigration laws changed, so too did the ability of these women to own and manage property, though they often faced racial and ethnic discrimination.

Immigrant Women’s Property Rights

Immigrant women have historically faced legal barriers to property ownership, including laws that restricted property rights based on citizenship status. These barriers were often compounded by racial and ethnic discrimination.

In the latter half of the 20th century and into the 21st century, changes in immigration and anti-discrimination laws have improved the ability of immigrant women to own property. However, certain immigrant women still face significant barriers to property ownership and access to financial services.

Final Thoughts on the Rights of Women to Own Property in America

The journey toward gender equality has been long and fraught with challenges, yet it underscores the remarkable resilience and tenacity of women who have fought tirelessly for their rights. The need to continue pushing for women’s rights remains as critical today as it has ever been, with the understanding that progress is neither linear nor guaranteed.

Remembering our shared history is not just about honoring the struggles and achievements of those who came before us. It is a powerful reminder of the importance of vigilance and action in the face of ongoing discrimination and inequality. As we move forward, it’s essential to build on the foundations laid by previous generations, advocating for policies and practices that ensure full and equal rights for all women. In doing so, we not only pay tribute to the legacy of those who have paved the way but also reaffirm our commitment to creating a more equitable and just society for future generations.

The battle for women’s rights, encapsulated in milestones like the Equal Credit Opportunity Act of 1974 and beyond, illustrates the continuous effort required to safeguard these hard-won freedoms. Our shared history as women is a testament to the power of collective action and the enduring spirit of equality.

Design Dash

Join us in designing a life you love.

Seven German Furniture Brands Known for Precision and Luxury

This guide profiles seven German furniture brands that pair engineering with craft and highlight their most significant pieces.

13 Adaptive Reuse Projects That Inspire Us at DesignDash

Let’s explore some of the most impressive adaptive reuse projects worldwide and share insights on how you can effectively showcase your own adaptive reuse work online as an architect or interior designer.

March 2026 Architecture & Interior Design Events You Can’t Miss

This guide outlines the most important March 2026 architecture and interior design events in the U.S. and abroad.

5 Podcast Episodes About Managing Your Interior Design Firm’s Finances

These five DesignDash episodes show how profit, billing, systems, and client dynamics shape a healthier interior design business.

Axel Vervoordt Reminds Us That Time and Use Are Design’s Collaborators

An editorial examination of Axel Vervoordt’s design philosophy and what it teaches designers about time and use as collaborators.

What Does a “Successful” Firm Look Like Beyond Revenue?

Laura and Melissa reflect on what defines a successful design firm beyond revenue, and why nonfinancial indicators can be equally important.