Melancholic Beauty & Moral Tales: All About the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

Summary

Reflection Questions

Journal Prompt

In the mid-19th century—amidst the complex societal and cultural landscape of Victorian England—the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood emerged as a distinctive artistic collective. Founded in 1848 by a group of young, avant-garde artists, this Brotherhood sought to rebel against the prevailing norms of the Royal Academy of Arts, which they perceived as formulaic and uninspired. At the heart of their philosophy was a return to the abundant detail, intense colors, and complex compositions that characterized art prior to the High Renaissance—hence the name “Pre-Raphaelite.” Their approach was not merely a stylistic choice but a broader artistic and moral endeavor—aiming to bring honesty, nature, and vibrancy back into English art, which they believed had become stagnant and superficial. In this article, we will explore the formation, ideals, and enduring influence of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood—setting the stage for a deeper understanding of their role in reshaping Victorian art and culture.

The Pre-Raphaelite Movement: Formation and Founding Members

Circumstances Leading to the Formation of this Pre-Raphaelite Circle

The formation of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in 1848 was a direct response to the artistic and cultural milieu of Victorian England. During this period, the art world was predominantly influenced by the Royal Academy of Arts, which advocated a style rooted in the ideals of the High Renaissance—particularly the work of Raphael.

This led to what the Brotherhood perceived as a formulaic and insipid approach to art—lacking in genuine emotion and connection to nature. The Industrial Revolution further contributed to this dissatisfaction, as it brought about rapid social changes and a sense of loss for the natural world. In this context, the Brotherhood was established as an act of rebellion and a call for a return to a more genuine, detailed, and nature-focused art.

Founding Members

Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Dante Gabriel Rossetti—born in 1828—was a pivotal figure in the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. His contributions as a poet, painter, and illustrator were instrumental in defining the aesthetic and philosophical underpinnings of the movement.

Rossetti’s work is characterized by its intense emotionality, intricate symbolism, and its blending of the visual and the literary. His art often featured medieval themes, romantic and mythological subjects, and a profound depth of feeling, reflecting his interest in the art and literature of the past. This was complemented by his use of rich, vivid colors and a focus on naturalistic detail, which became hallmarks of the Pre-Raphaelite style.

In addition to his paintings, Rossetti was also a respected poet. His poetry—much like his visual art—was marked by its sensuous language and exploration of themes like love, beauty, and mortality. This literary work further enriched the intellectual and cultural framework of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

Rossetti’s influence extended beyond his own artistic output. He was a mentor and inspiration to other artists within the Brotherhood and was instrumental in defining the group’s artistic direction. His vision and dedication to the Pre-Raphaelite ideals helped establish the movement as a significant force in Victorian art.

are you a fine artist or photographer?

However, Rossetti’s life was not without turmoil. He faced personal struggles, including bouts of mental illness and the tragic death of his wife—Elizabeth Siddal—which profoundly affected him and his work. Despite these challenges, or perhaps because of them, Rossetti’s art maintained a deep emotional resonance that continued to evolve throughout his career.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti died in 1882, leaving behind a legacy that has had a lasting impact on the art world. His work remains celebrated for its beauty, emotional depth, and its synthesis of the visual and the poetic—securing his place as one of the most influential artists of the Pre-Raphaelite movement.

William Holman Hunt

William Holman Hunt—born in 1827—was a founding member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and a prominent figure in the Victorian art scene. His work is distinguished by its meticulous attention to detail, vibrant use of color, and incorporation of deep moral and religious themes—all of which were central to the Pre-Raphaelite movement.

Hunt’s artistic philosophy was rooted in a commitment to realism. He believed in portraying the world as it truly was, with a focus on accurate and detailed representations. This approach is evident in his landscapes and depictions of figures, where every element was rendered with precision and care. His use of color was particularly notable for its intensity and its ability to convey mood and symbolism.

A recurring theme in Hunt’s work was the exploration of moral and spiritual questions. Many of his paintings contained allegorical elements—reflecting his personal beliefs and the broader Victorian concern with religion and morality. This is exemplified in works like “The Light of the World”—which depicts Christ as the bringer of spiritual enlightenment—and “The Awakening Conscience”—a portrayal of moral redemption.

Fuel your creative fire & be a part of a supportive community that values how you love to live.

subscribe to our newsletter

*please check your Spam folder for the latest DesignDash Magazine issue immediately after subscription

Hunt’s dedication to the Pre-Raphaelite ideals often led him to venture into challenging and unconventional subjects. He was not afraid to address contemporary social issues or to reinterpret traditional religious themes in new and thought-provoking ways. This boldness—combined with his technical skill—made him a significant and influential figure within the Brotherhood.

Despite facing criticism and misunderstanding from the art establishment of his time, Hunt remained steadfast in his artistic vision. His perseverance and commitment to his principles not only shaped his own body of work but also contributed to the enduring legacy of the Pre-Raphaelite movement.

William Holman Hunt passed away in 1910—leaving behind a rich legacy of artwork that continues to be celebrated for its beauty, complexity, and depth. His contributions to Victorian art and the Pre-Raphaelite movement have secured his place as one of the most important and influential artists of his era.

John Everett Millais

John Everett Millais—born in 1829—emerged as a key figure in the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Millais was renowned for his exceptional technical skill, which—combined with the innovative principles of the Brotherhood—resulted in a body of work that was both groundbreaking and enduringly influential.

Millais’ artistic journey began with prodigious talent displayed at a young age—leading to early acclaim. As a founding member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, he embraced and contributed to the group’s dedication to realism, detailed compositions, and the use of vibrant colors. His works from this period—such as “Ophelia” and “Christ in the House of His Parents”—are celebrated for their intricate detail and emotional depth—showcasing a meticulous approach to both subject matter and technique.

Despite the initial controversy and criticism these works received, Millais’ commitment to the Pre-Raphaelite ideals was evident in his persistent exploration of themes from literature, history, and nature. His paintings often featured complex narratives—depicted with a clarity and precision that was revolutionary for the time.

As his career progressed, Millais’ style evolved, showing a shift towards a broader and more accessible form of art. This evolution reflected both personal growth and the changing tastes of the Victorian art world. He achieved great success and recognition, culminating in his appointment as the President of the Royal Academy of Arts. This role marked a significant transformation from his early days as a radical member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

Millais’ later works, while differing in style from his earlier Pre-Raphaelite pieces, continued to be characterized by technical excellence and a keen sense of composition and color. Throughout his career—whether working within the Pre-Raphaelite aesthetic or beyond it—Millais remained a pivotal figure in British art.

John Everett Millais passed away in 1896, leaving behind a diverse and influential body of work. His legacy lies not only in his contributions to the Pre-Raphaelite movement but also in his role in shaping the broader course of Victorian art—making him one of the most important artists of his generation.

Other Members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

James Collinson

James Collinson—born in 1825—was a lesser-known but integral member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood—contributing to the early formation and philosophy of the group. His career—marked by a relatively modest output and a fluctuating commitment to the Pre-Raphaelite ideals—reflects the complex dynamics and evolving nature of the movement during its formative years.

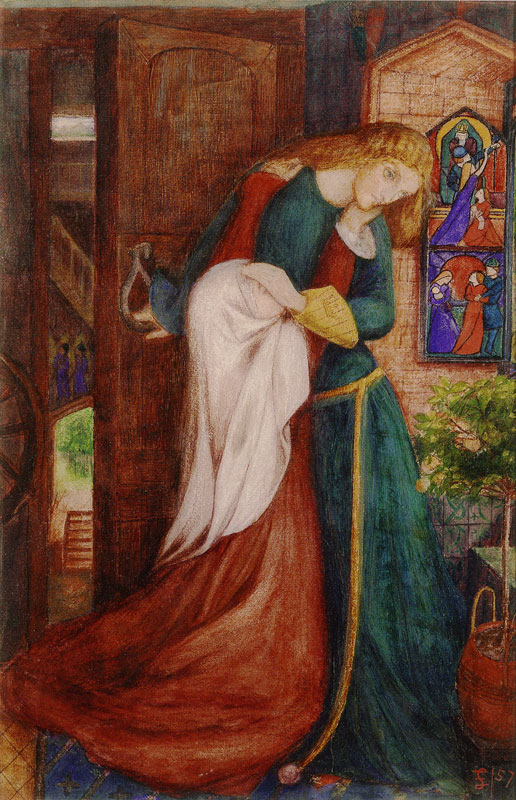

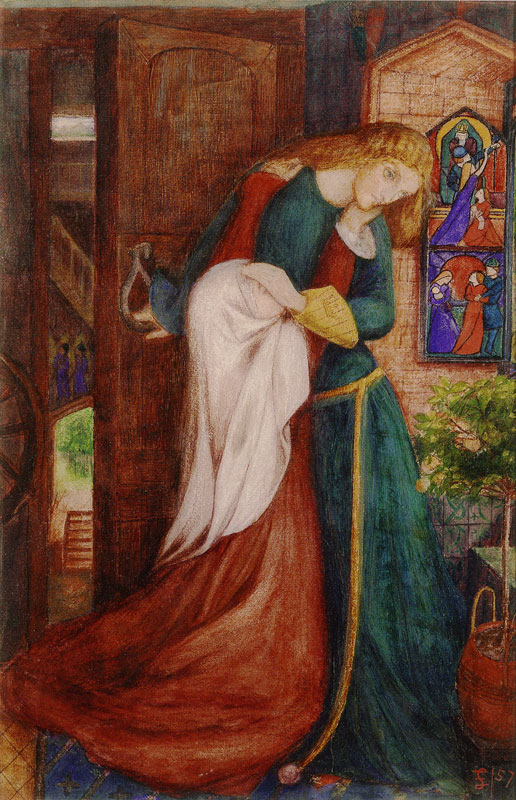

Collinson’s artistic style initially aligned closely with the Pre-Raphaelite principles of detailed realism, vivid use of color, and complex thematic content. His works often exhibited the meticulous attention to detail and the emphasis on naturalism that were hallmarks of the Brotherhood. This is evident in paintings such as “The Renunciation of St. Elizabeth of Hungary,” which showcases his ability to blend realism with a rich, narrative-driven approach.

However, Collinson’s career was characterized by a certain level of inconsistency—partly due to his wavering dedication to the Brotherhood. He left the group briefly, only to rejoin and then leave again—reflecting a personal struggle with the artistic direction and the rigorous demands of the Pre-Raphaelite style. This indecision impacted his artistic output, which, while skilled, lacked the prolificacy and consistent evolution seen in the works of his peers.

Despite his less prominent role, Collinson’s contributions to the Pre-Raphaelite movement were significant—especially in its early stages. His work embodied the group’s initial ethos and helped establish the foundational principles that would later be developed and expanded by other members.

James Collinson passed away in 1881—leaving behind a body of work that, though limited in quantity, played a part in the broader tapestry of the Pre-Raphaelite movement. His artistic journey offers insight into the diverse paths and varying commitments of the artists within this influential group—underscoring the dynamic and multifaceted nature of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

Frederic George Stephens

Frederic George Stephens—born in 1827—was a unique figure within the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood—known more for his role as a critic and art writer than for his contributions as a painter. His involvement with the Brotherhood highlights the diverse talents and roles that underpinned the movement—extending beyond the creation of art to its promotion and intellectual defense.

Stephens’ journey with the Pre-Raphaelites began as a painter, but he soon found his true calling in the realm of art criticism. As one of the founding members of the Brotherhood, his early artistic endeavors aligned with the Pre-Raphaelite principles of realism and detail. However, his transition to writing marked a significant shift in his contribution to the movement. His critical writings and reviews became an essential means of communicating and defending the ideals and works of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood to a broader audience.

As a critic, Stephens was a passionate advocate for the Pre-Raphaelite cause. His writings were instrumental in articulating the group’s philosophy and aesthetic—providing both support and intellectual rigor to their artistic vision. His critiques often addressed the broader cultural and artistic contexts of the Pre-Raphaelite works—offering insights into their significance and impact.

Despite his limited output as a painter, Stephens’ role within the Brotherhood was pivotal. His transition from artist to critic reflects the multifaceted nature of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, which encompassed not only a new style of painting but also a new way of thinking about and engaging with art. His contributions helped to shape the public perception and understanding of the Brotherhood—playing a crucial role in the spread and acceptance of their ideas.

Frederic George Stephens passed away in 1907, leaving behind a legacy as a key intellectual figure of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. His work as a critic and writer provides a valuable perspective on the movement—demonstrating the importance of critical discourse in the evolution and reception of art.

Thomas Woolner

Thomas Woolner—born in 1825—was a distinguished sculptor and poet who played a significant role in the early development of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. His contributions—primarily in sculpture—set him apart within a movement more commonly associated with painting and illustration—highlighting the diverse artistic expressions within the Brotherhood.

Woolner’s work in sculpture was marked by a keen adherence to the Pre-Raphaelite principles of detailed realism and emotional depth. His sculptures often featured figures from history, literature, and mythology—rendered with a meticulous attention to physical detail and expressive qualities. This focus on realism was in stark contrast to the more idealized and abstract sculptures typical of the period—making Woolner’s work both innovative and influential.

In addition to his sculptural work, Woolner was also an accomplished poet—further illustrating the interdisciplinary nature of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. His poetry—like his sculptures—often explored themes of love, nature, and mythology, and reflected the same attention to detail and depth of emotion.

Woolner’s role within the Brotherhood was not limited to his artistic output. He was an active member of the group—contributing to discussions and debates that shaped the movement’s philosophy and aesthetic direction. His commitment to the Pre-Raphaelite ideals—both in his art and in his intellectual engagement—was a testament to the movement’s dedication to redefining artistic expression in the Victorian era.

Although Woolner eventually moved to Australia for several years, his influence on the Pre-Raphaelite movement remained significant. His early works and participation in the group helped lay the foundations for the development of Pre-Raphaelitism and its impact on Victorian art.

Thomas Woolner passed away in 1892, leaving behind a legacy as a key figure in the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. His unique contributions—particularly in the realm of sculpture—enriched the movement and broadened its scope—underscoring the diversity and richness of the Pre-Raphaelite artistic vision.

William Michael Rossetti

William Michael Rossetti—born in 1829—was a notable figure within the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood—distinguished not for his artistic creations but for his critical and scholarly contributions to the movement. As the brother of Dante Gabriel Rossetti—one of the founding members—William Michael played a pivotal role in shaping the intellectual and literary aspects of the Brotherhood.

Unlike the other members who were primarily visual artists, William Michael’s involvement with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was centered on his skills as a critic, editor, and writer. His acute understanding of the artistic and literary landscape of the time allowed him to provide insightful critiques and articulate the philosophies underlying the Pre-Raphaelite movement. This intellectual contribution was crucial in defining and disseminating the group’s ideas and aesthetics to a broader audience.

Rossetti was instrumental in documenting the works and history of the Brotherhood. His writings and compilations provided a coherent narrative of the movement—offering context and analysis that helped solidify its place in art history. His editorial work included collaborating on publications that were central to the Brotherhood’s mission—such as “The Germ,” which was a periodical that aimed to propagate Pre-Raphaelite ideas and art.

Moreover, William Michael’s role extended beyond the confines of the Brotherhood. He was an active figure in the wider artistic and literary communities—fostering connections and advocating for the recognition of Pre-Raphaelite art. His efforts were significant in gaining acceptance and appreciation for the movement within the larger Victorian cultural sphere.

William Michael Rossetti passed away in 1919—leaving behind a rich legacy as a critical voice and chronicler of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. His contributions—though less visible than the paintings and sculptures of his peers—were no less important in shaping and preserving the legacy of this influential artistic movement. His scholarly and critical work continues to be a key resource for understanding the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and its impact on the art world.

Artists Who Contributed to the Movement But Were Not Part of the Brotherhood

Ford Madox Brown

Ford Madox Brown—born in 1821—stands as a significant, though unofficial, contributor to the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. His association with the movement—despite never formally joining—was marked by a shared dedication to realism, detail, and social commentary, which significantly influenced the Brotherhood’s development.

Brown’s artistic style was characterized by its vivid realism and strong narrative quality. He had a keen eye for detail and a commitment to portraying scenes and characters with authenticity and depth. This approach aligned closely with the Pre-Raphaelite ideals of rejecting the conventional and idealized forms of art prevalent in Victorian England. His works often contained social and moral commentary—reflecting his interest in the realities of contemporary life and his desire to use art as a means of social critique.

One of Brown’s most famous works, “Work,” exemplifies his style and thematic concerns. The painting is a complex tableau of the working class in Victorian society, rich in detail and symbolism. It demonstrates his skill in combining realism with a narrative approach—a characteristic that deeply resonated with the Pre-Raphaelite artists.

Brown also had a profound influence on the younger members of the Brotherhood. He was a mentor and role model for artists like Dante Gabriel Rossetti and William Holman Hunt—both of whom admired his dedication to artistic innovation and his refusal to conform to the artistic norms of the time.

His contributions to the arts extended beyond painting. Brown was involved in the design and decorative arts, participating in projects that reflected the integration of art and life—a principle later central to the Arts and Crafts Movement.

Ford Madox Brown passed away in 1893, leaving behind a body of work that not only influenced the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood but also made a lasting impact on Victorian art. His commitment to realism, social relevance, and artistic integrity established him as a key figure in the transition from traditional Victorian art to the more varied and innovative styles that followed. His legacy continues to be recognized for its significant contribution to the evolution of British art in the 19th century.

John William Waterhouse

John William Waterhouse—born in 1849—emerged as a prominent figure associated with the later phase of the Pre-Raphaelite movement. His work, characterized by romantic and mythological themes, continued and expanded upon the aesthetic and philosophical ideals of the early Pre-Raphaelites—making him a key figure in the movement’s enduring legacy.

Waterhouse’s artistic style is noted for its blend of classical Pre-Raphaelite traits and his own unique sensibilities. His paintings often feature strong, enchanting female figures drawn from mythology, literature, and history, set against rich, naturalistic landscapes. This thematic focus reflected the Pre-Raphaelite fascination with romantic, historical, and mythological subjects, but with a distinctive flair that was unmistakably Waterhouse’s.

A hallmark of his work is the vivid, almost ethereal quality of his colors and the dreamlike atmosphere he created in his paintings. This approach—while maintaining the Pre-Raphaelite emphasis on beauty and detail—also introduced a sense of mystique and narrative depth. His famous works—such as “The Lady of Shalott” and “Hylas and the Nymphs”—exemplify this style, with their strong emphasis on mood and storytelling.

Waterhouse’s contribution to the Pre-Raphaelite movement was significant in its continuation and evolution of the group’s ideals. While he came to prominence towards the end of the Pre-Raphaelite period, his work helped to sustain the movement’s influence into the 20th century—bridging the gap between the Victorian era and the emerging styles of the new century.

John William Waterhouse passed away in 1917—leaving a legacy as a pivotal artist who upheld and evolved the Pre-Raphaelite tradition. His body of work continues to be celebrated for its enchanting beauty, technical mastery, and its unique position within the broader scope of the Pre-Raphaelite movement.

Edward Burne-Jones

Edward Burne-Jones—born in 1833—was a central figure in the later phase of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, known for his ethereal and romantic interpretations of mythological and medieval subjects. Although not a founding member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, his work and philosophy were heavily influenced by the movement, and he became one of its most enduring and influential exponents.

Burne-Jones’ artistic style was characterized by its dreamlike quality, rich in symbolism and beauty. His paintings often featured elongated, ethereal figures set in romantic, otherworldly landscapes. This approach was a continuation and evolution of the Pre-Raphaelite focus on detailed realism, but with a more mystical and idealized bent. He was particularly renowned for his depiction of mythological and medieval themes, which he rendered with a poetic sensibility that resonated with the Victorian fascination with chivalry and romance.

His contributions to the arts extended beyond painting. Burne-Jones was also instrumental in the world of decorative arts—working closely with William Morris, another key figure associated with the Pre-Raphaelites. Together, they played a significant role in the Arts and Crafts Movement—emphasizing the importance of craftsmanship and design in response to the industrialization of the era.

Burne-Jones’ influence within the Pre-Raphaelite movement and Victorian art—in general—was profound. His works helped to sustain and expand the reach of the Pre-Raphaelite ideals into the late 19th century and beyond. His unique blending of romanticism, mythology, and symbolism paved the way for future artistic movements—including Symbolism and Aestheticism.

Edward Burne-Jones passed away in 1898—leaving behind a legacy that remains influential in the world of art. His commitment to beauty and his visionary approach to painting and design have secured his place as one of the most important and revered artists of the Pre-Raphaelite movement and the broader landscape of Victorian art.

Notable Pre-Raphaelite Women Artists

There were several women artists associated with the Pre-Raphaelite movement, although they were not formally recognized as members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. These women played a significant role in the development and spread of Pre-Raphaelite ideas and aesthetics—often contributing through their own artistic work or as muses and collaborators. Some of the notable women artists associated with the Pre-Raphaelite movement include the following.

Elizabeth Siddal (1829–1862)

Perhaps the most famous of the Pre-Raphaelite women, Siddal was initially known as a model for artists like Dante Gabriel Rossetti and John Everett Millais. However, she was also a talented artist and poet in her own right. Her drawings and paintings—characterized by their delicate lines and melancholic beauty—embodied the Pre-Raphaelite style.

Evelyn De Morgan (1855–1919)

A later follower of the movement, De Morgan’s work was heavily influenced by the Pre-Raphaelites—particularly in her use of vivid colors and her focus on spiritual and mythological themes. She was known for her allegorical paintings and her commitment to exploring feminist themes in her work.

Maria Spartali Stillman (1844–1927)

Spartali Stillman—of Greek descent—was one of the few women of her era to achieve recognition for her work as an artist. She was also a model for several Pre-Raphaelite painters. Her paintings often featured romantic and literary themes and were noted for their vivid detail and rich coloration.

May Morris (1862–1938)

The daughter of William Morris—a key figure associated with the Pre-Raphaelites—May Morris was an accomplished designer, particularly in the fields of embroidery and wallpaper design. She played a significant role in the Arts and Crafts Movement—carrying forward the Pre-Raphaelite legacy in design and craftsmanship.

Jane Morris (1839–1914)

Initially known as a model and muse for the Pre-Raphaelites—particularly for Rossetti and her husband William Morris—Jane Morris later emerged as a talented embroiderer and designer. She contributed significantly to the Arts and Crafts Movement and was influential in translating Pre-Raphaelite aesthetics into textile designs.

Early Influences and Inspirations

The early influences on the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood were varied and complex. Medieval art was an early Pre-Raphaelite influence—inspiring the Brotherhood’s focus on realism, nature, and complex, layered symbolism. Literary works—especially those of Dante Alighieri and John Milton—were also influential—providing a rich source of themes and subjects for their art.

Additionally, the growing interest in nature and the natural sciences in Victorian society—partly as a reaction to industrialization, encouraged their focus on detailed and accurate depictions of the natural world. These influences combined to form a unique artistic vision that sought to break away from the conventions of the time and forge a new path in the world of art.

Artistic Principles and Style

Detailed Examination of the Pre-Raphaelite Aesthetic

The Pre-Raphaelite aesthetic is characterized by its vivid attention to detail, its vibrant use of color, and an overarching commitment to realism. Unlike the grandiose and often idealized narratives of Renaissance art, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood believed in a more authentic and unvarnished view of the world.

This was evident in their portrayal of subjects, which often included natural landscapes, medieval scenes, and figures drawn from mythology and literature. The Brotherhood’s approach was not merely visual. It was deeply intertwined with their moral and philosophical views—reflecting a desire to connect art with truth and nature.

Emphasis on Realism, Nature, and Vivid Colors

Realism was a cornerstone of the Pre-Raphaelite movement. The artists endeavored to depict the world with precision and detail—often spending long hours studying their subjects in natural light to capture their true essence. This focus extended to their portrayal of human figures, where they sought to capture genuine emotion and physical accuracy—a stark contrast to the idealized forms popular at the time.

Nature played a central role in their work. The Brotherhood was fascinated by the natural world—seeing it as a direct path to understanding truth and beauty. Their landscapes are notable for their intricate detail and vibrant colors, which were meant to evoke the awe and wonder of the natural world.

The use of vivid colors was another defining feature. Pre-Raphaelite paintings are often immediately recognizable for their intense, almost luminous hues. These Pre-Raphaelite painting techniques were used not just for aesthetic impact but also to convey deeper emotional and symbolic meanings.

Rejection of the Conventional Artistic Norms of the Time

The Brotherhood’s approach was a deliberate rejection of the artistic norms established by the Royal Academy of Arts. They opposed the Academy’s promotion of the Renaissance artists—particularly Raphael, as the ideal standard for art. The Brotherhood felt that this focus led to a stale and formulaic style that lacked emotional depth and authenticity. They sought instead to revive the richness and complexity they admired in earlier art forms—particularly those before the High Renaissance.

Influence of Medieval Art and Culture

Beyond early Renaissance art, Medieval art and culture had a profound impact on the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. They were drawn to the period’s rich symbolism, its emphasis on narrative, and its integration of art with spiritual and moral themes. The Brotherhood saw medieval art as uncorrupted by the academic standards that they felt had constrained later artistic developments.

This influence is evident in their choice of subjects—often drawn from medieval history and literature—and their stylistic elements—such as the use of symbolism and complex compositions. The medieval influence was also aligned with the Victorian era’s romanticized view of the past, which saw it as a time of greater authenticity and moral clarity.

Key Works and Themes

Analysis of Significant Artworks by the Brotherhood

“Ophelia” by John Everett Millais (1851-52)

This painting depicts the tragic character from Shakespeare’s “Hamlet” floating in a stream before her death. Millais’ attention to botanical detail in the surrounding nature and the haunting beauty of Ophelia herself are exemplary of the Pre-Raphaelite focus on realism and emotional depth.

“The Lady of Shalott” by William Holman Hunt (1888-1905)

Inspired by Alfred Tennyson’s poem, this work illustrates the moment the Lady of Shalott curses herself to death. Hunt’s use of vibrant colors and meticulous detail encapsulates the Pre-Raphaelite’s dedication to bringing literary narratives to life.

“Proserpine” by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1874)

Rossetti’s painting of the Roman goddess Proserpine is imbued with symbolic elements—such as the pomegranate, representing her captivity in the underworld. The fusion of mythology and emotional expression is central to the Pre-Raphaelite style.

“Christ in the House of His Parents” by John Everett Millais (1849-50)

This depiction of a young Jesus Christ in a carpenter’s workshop was controversial for its realistic portrayal of a sacred subject—challenging the conventional religious art of the time.

“The Awakening Conscience” by William Holman Hunt (1853)

In this work, Hunt explores the theme of moral redemption—showing a woman rising from her lover’s lap as she experiences a moment of spiritual awakening—a reflection of the Victorian moral compass.

“Beata Beatrix” by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1864-70)

This painting—portraying the death of Beatrice from Dante Alighieri’s “La Vita Nuova”—is a blend of romanticism and symbolism. Rossetti’s personal grief over the death of his wife—Elizabeth Siddal—is evident in the emotional intensity of the work.

“Isabella” by John Everett Millais (1848-49)

Based on John Keats’ poem, this painting’s narrative storytelling and detailed depiction of the characters’ emotions are characteristic of the Pre-Raphaelite approach.

“The Light of the World” by William Holman Hunt (1851-53)

This allegorical painting of Christ knocking on a door represents Hunt’s religious and moral themes, with an emphasis on spiritual enlightenment.

“Ecce Ancilla Domini!” by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1849-50)

Depicting the Annunciation, this work is notable for its simplistic style and the unusual depiction of the Virgin Mary, which challenged the traditional religious iconography.

Exploration of Common Themes: Nature, Medievalism, Romanticism, and Mythology

The Pre-Raphaelites frequently explored themes rooted in nature, medievalism, romanticism, and mythology. Their focus on nature was part of a larger Victorian fascination with the natural world—seen as a counterpoint to the era’s rapid industrialization. Medieval themes were aligned with the Victorian romanticization of the past—viewed as a purer, more noble era.

Romanticism was evident in their emotional intensity and idealization of love and beauty. Finally, their use of mythology allowed them to explore universal themes and human experiences in a time when questions of faith and science were prominent in the public consciousness.

Discussion on How These Themes Reflected the Broader Victorian Culture

These themes were a direct reflection of the broader Victorian culture, which was grappling with the effects of industrialization, shifts in religious thought, and the role of art in society. The Pre-Raphaelites’ focus on nature and medievalism offered an escape to a simpler, more authentic world. Their romanticism was a response to the era’s moral and social constraints—offering a space for emotional expression and exploration.

The use of mythology and historical subjects allowed them to comment on contemporary issues indirectly, providing a lens through which to examine the complexities of Victorian society. Through these themes, the Pre-Raphaelites not only challenged artistic conventions but also engaged with the pressing cultural and philosophical debates of their time.

Criticisms and Reception

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood’s work initially met with a mixed reception from both the public and critics. When the group first exhibited their paintings, they were met with significant controversy and criticism. The art establishment—particularly the Royal Academy of Arts—was taken aback by the Brotherhood’s blatant disregard for the established norms of painting. Critics often found their works to be jarringly realistic, overly detailed, and strikingly different in their use of color and composition.

The public, accustomed to the more idealized and polished works of the time, also had mixed reactions—ranging from intrigue to outright disdain. The Brotherhood’s works were seen as radical and unconventional—challenging the aesthetic tastes of the Victorian audience. Eventually, key galleries like Walker Art Gallery, Lady Lever Art Gallery, and others accepted these young artists and their work.

Analysis of the Criticisms: What Were the Main Points of Contention?

The criticisms of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood centered on several key points. Firstly, their commitment to realism was seen as unrefined and even vulgar—especially in their depiction of religious and historical subjects. The intense and sometimes harsh realism of their work was perceived as a departure from the idealized beauty that was prevalent in art at the time.

Secondly, their use of bright, vivid colors was often deemed garish and unnatural—contrasting sharply with the more subdued palettes of conventional Victorian painting. Another major point of contention was their subject matter. The Brotherhood’s focus on medieval themes—and their portrayal of contemporary moral and social issues through historical and literary lenses—was considered by some to be inappropriate or overly sentimental.

In response to the criticism, the members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood remained steadfast in their artistic convictions. Rather than conforming to the expectations of critics and the public, they continued to develop and refine their style. They also took to writing letters and articles in defense of their work—articulating their principles and challenging the criticisms leveled against them.

This response was reflective of the Brotherhood’s broader purpose: not just to create art, but to reform and challenge the prevailing artistic norms of their time. Over time, as the radical nature of their work became more accepted, and as tastes and perceptions in the art world began to shift, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood gained a more appreciative audience and critical recognition—securing their place in the history of art.

Influence and Legacy

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood—with their innovative approach to art—had a profound impact on the later Victorian art scene and on artists who followed. Their emphasis on realism, nature, and emotion in art was a significant departure from the dominant trends of their time and paved the way for a more diverse range of artistic expressions.

This influence extended beyond painting to include literature, design, and decorative arts. Artists influenced by the Pre-Raphaelite movement often adopted similar themes and techniques—emphasizing detail, vibrant color, and complex composition in their work. The Brotherhood’s dedication to portraying realistic, emotional, and naturalistic subjects inspired a generation of artists to explore beyond the boundaries of traditional Victorian art.

Their Role in the Arts and Crafts Movement

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood’s influence was particularly significant in the Arts and Crafts Movement, which emerged in the latter half of the 19th century. This movement—which advocated for craftsmanship and design in reaction to the industrialization of production—found resonance with the Brotherhood’s ideals.

The focus on handcrafted quality, the beauty of natural forms, and the integration of art into everyday life were principles shared by both the Pre-Raphaelites and the Arts and Crafts Movement. Members of the Brotherhood—such as William Morris, who was closely associated with the movement—played a crucial role in its development, applying their artistic principles to a range of mediums including textiles, wallpaper, and furniture design.

Long-term Legacy in British and Global Art

The long-term legacy of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in British and global art is substantial. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood influenced many subsequent movements. They are credited with helping to revitalize British art in the 19th century—bringing a new depth and richness to it. Their work continues to be celebrated for its beauty, emotional depth, and technical skill.

The Brotherhood’s influence extended well beyond the Victorian era—contributing to the development of various art movements in the 20th century, including Symbolism and Aestheticism. Globally, their impact is seen in the way they inspired artists around the world to pursue realism and personal expression in art—challenging traditional norms and conventions.

The Pre-Raphaelites’ integration of art, poetry, and design also foreshadowed the interdisciplinary nature of modern and contemporary art. Their legacy endures in the continued popularity and relevance of their work in art galleries and museums worldwide, as well as in the ongoing scholarly interest in their contribution to the history of art.

Later Years and Dissolution

As the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood moved into the latter part of the 19th century, the group began to evolve and diverge in various artistic directions. The initial unified vision that had brought the members together started to dissipate as individual artists developed their unique styles and interests.

Some members—like Dante Gabriel Rossetti—delved deeper into the symbolic and romantic aspects of their work—moving away from the strict realism that had characterized their earlier efforts. Others—such as William Holman Hunt—continued to pursue the original Pre-Raphaelite principles in their art. This period also saw the members of the Brotherhood engage more significantly in other art forms—such as poetry and decorative arts—which further diversified their artistic output.

The decline and eventual dissolution of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood were due to several factors. The diverging artistic paths of its members were a major contributing factor, as the lack of a unified vision led to a gradual disbanding of the group. Additionally, the art world itself was changing, with new movements and styles emerging that diverted attention and interest away from Pre-Raphaelite art. The death of key members also played a role in the group’s dissolution. By the end of the 19th century, the Brotherhood had effectively ceased to exist as an active artistic collective—although its influence continued.

Final Thoughts on the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood—with its revolutionary approach to art and aesthetics—left an indelible mark on the Victorian art scene and the broader art world. The Brotherhood challenged the artistic norms of their time—advocating for a return to detailed realism, vivid coloration, and complex thematic content. Their works—inspired by nature, medievalism, and romanticism—not only reflected the cultural and societal undercurrents of their era but also paved the way for future artistic movements.

The legacy of the Pre-Raphaelites endures in their influence on the Arts and Crafts Movement, the evolution of British art, and the continued admiration and study of their work. The Brotherhood’s commitment to artistic integrity and their pursuit of a deeper, more emotionally resonant form of art continue to resonate—underscoring their enduring significance in the history of art.