So Much More Than Ernest Hemingway’s Wife: Novelist and War Correspondent Martha Gellhorn

Summary

Reflection Questions

Journal Prompt

At DesignDash, we celebrate women in the arts, sciences, and other male-dominated fields. A prominent figure in 20th-century journalism and literature, Martha Gellhorn was renowned for her tenacity and skill as a war correspondent and her accomplishments as a novelist. Her career spanned several decades, during which she covered major global conflicts, including the Spanish Civil War and World War II, bringing a vivid and human perspective to the harrowing realities of war. Gellhorn’s literary contributions extend beyond journalism, with a body of work that includes novels and essays reflecting her experiences and observations. She was one of several wives of Ernest Hemingway, which has unfairly obscured her incredible body of work. In fact, each of Hemingway’s wives should be remembered as individuals, not as mere appendages to the troubled author. While her marriage to the novelist is a notable aspect of her personal life and often receives attention, we will focus primarily on Gellhorn’s individual achievements, underscoring her significant and independent impact in the realms of journalism and literature.

Martha Gellhorn’s Early Life and Beginnings

Martha Gellhorn was born on November 8, 1908, in St. Louis, Missouri, to a family with progressive social views. She received her education from Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania, although she left before graduating to pursue a career in journalism. Her early journalistic endeavors included reporting for the Albany Times Union in New York. Gellhorn’s initial journalistic work, characterized by a focus on social issues, laid the groundwork for her later career as a war correspondent.

Her Early Literary Works and Their Reception

Gellhorn’s early literary career was marked by the publication of her first novel, What Mad Pursuit (1934), which garnered moderate attention. What Mad Pursuit revolves around the lives of three college friends. The narrative explores their quests for fulfillment, meaning, and sexual adventure, which ultimately lead them to face various forms of disappointment and life challenges. The story begins with their time in college and follows their divergent paths as they confront the realities of adulthood and the consequences of their choices.

The novel received a lukewarm reception from critics, with some describing it as “palpable juvenilia” and others labeling it “amateurish.” This reception was particularly disappointing to Gellhorn, who later rarely mentioned the book in her list of published works. The story’s portrayal of the characters’ struggles with societal expectations and personal desires was seen as an ambitious but not entirely successful attempt at capturing the complexities of young women’s lives during that era. The book, despite its historical significance as Gellhorn’s debut novel, has largely been overlooked in the context of her more celebrated works in journalism and literature

She followed this with The Trouble I’ve Seen (1936), a collection of short stories based on her experiences of the Great Depression while working for the Federal Emergency Relief Administration. This work received critical acclaim for its unflinching portrayal of poverty and hardship in America, establishing Gellhorn as a significant voice in social journalism and literature of her time.

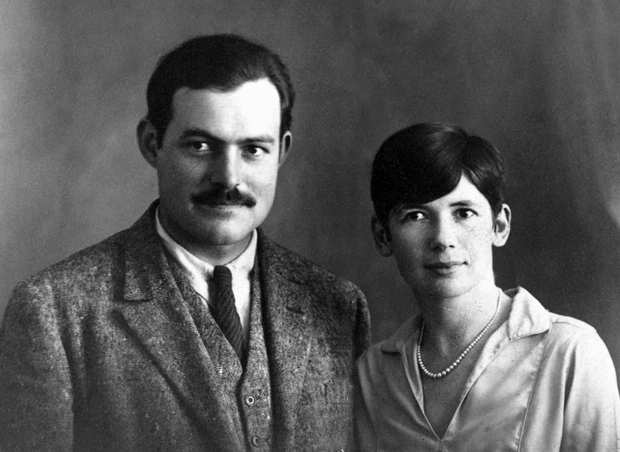

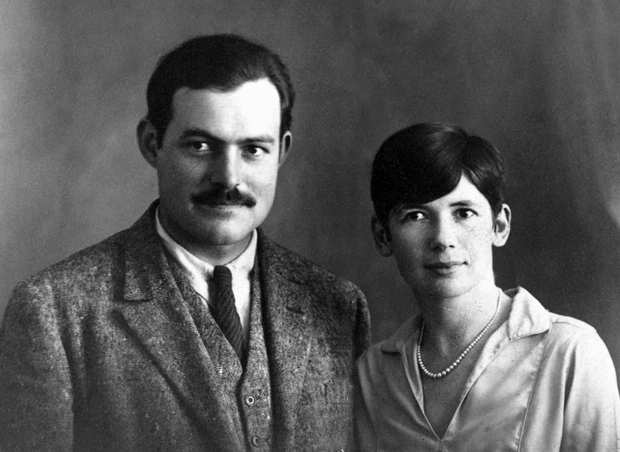

Her Marriage to Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Hemingway’s wives included Elizabeth Hadley Richardson, Pauline Pfeiffer, Mary Welsh, and Martha Gellhorn. Martha was his third wife. Martha Gellhorn met Ernest Hemingway in 1936 in Key West, Florida.

Their relationship began as a professional connection, with both sharing a passion for writing and journalism. By 1937, their relationship had evolved, and they traveled together to Spain to cover the Spanish Civil War, a pivotal event that cemented their romantic and professional bond. Gellhorn and Hemingway married in 1940, marking the start of a tumultuous union.

Their marriage was characterized by mutual respect for each other’s literary talents, but also marred by professional rivalry and Hemingway’s discomfort with Gellhorn’s frequent absences due to her war correspondence assignments. The marriage ended in 1945, following years of growing estrangement.

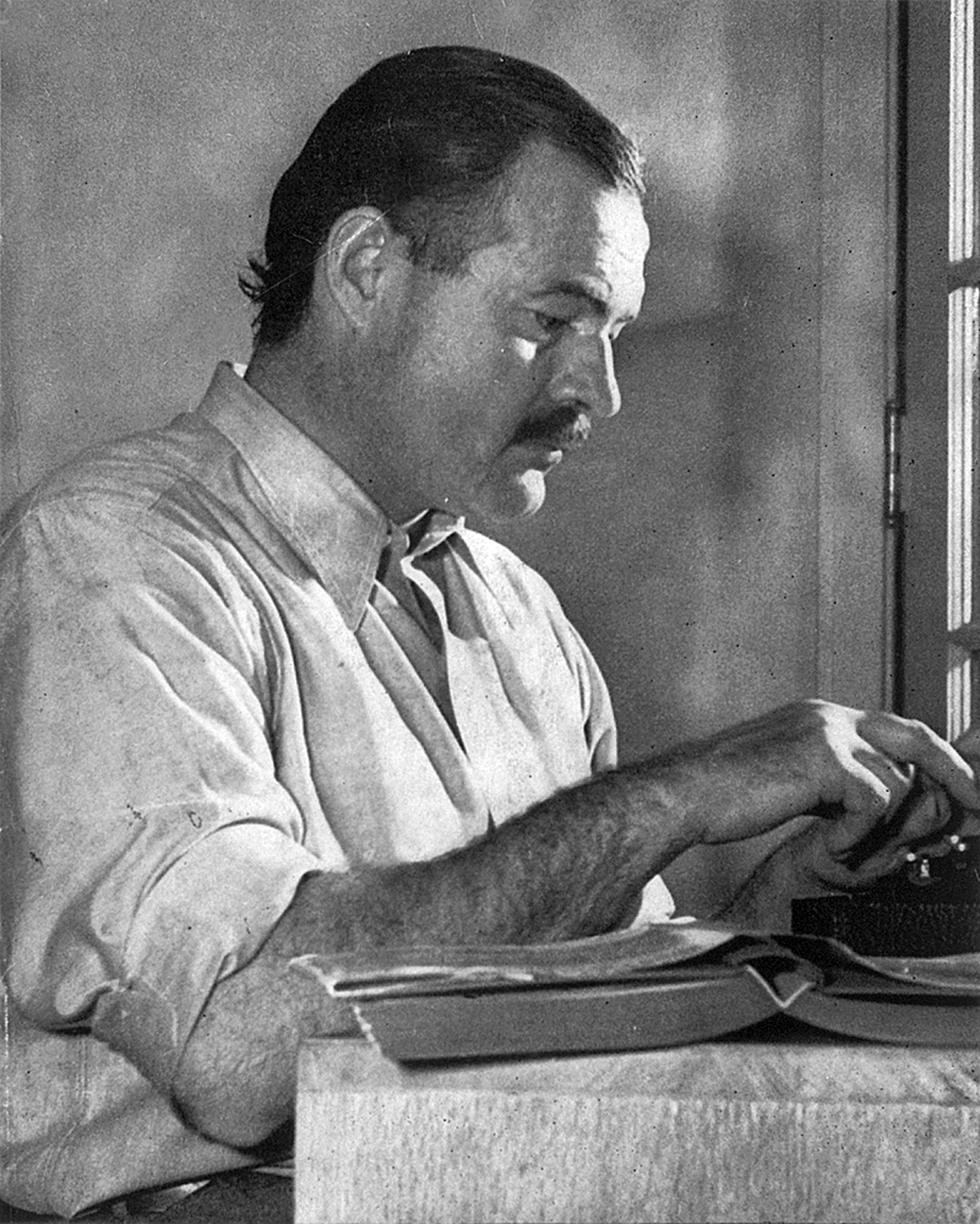

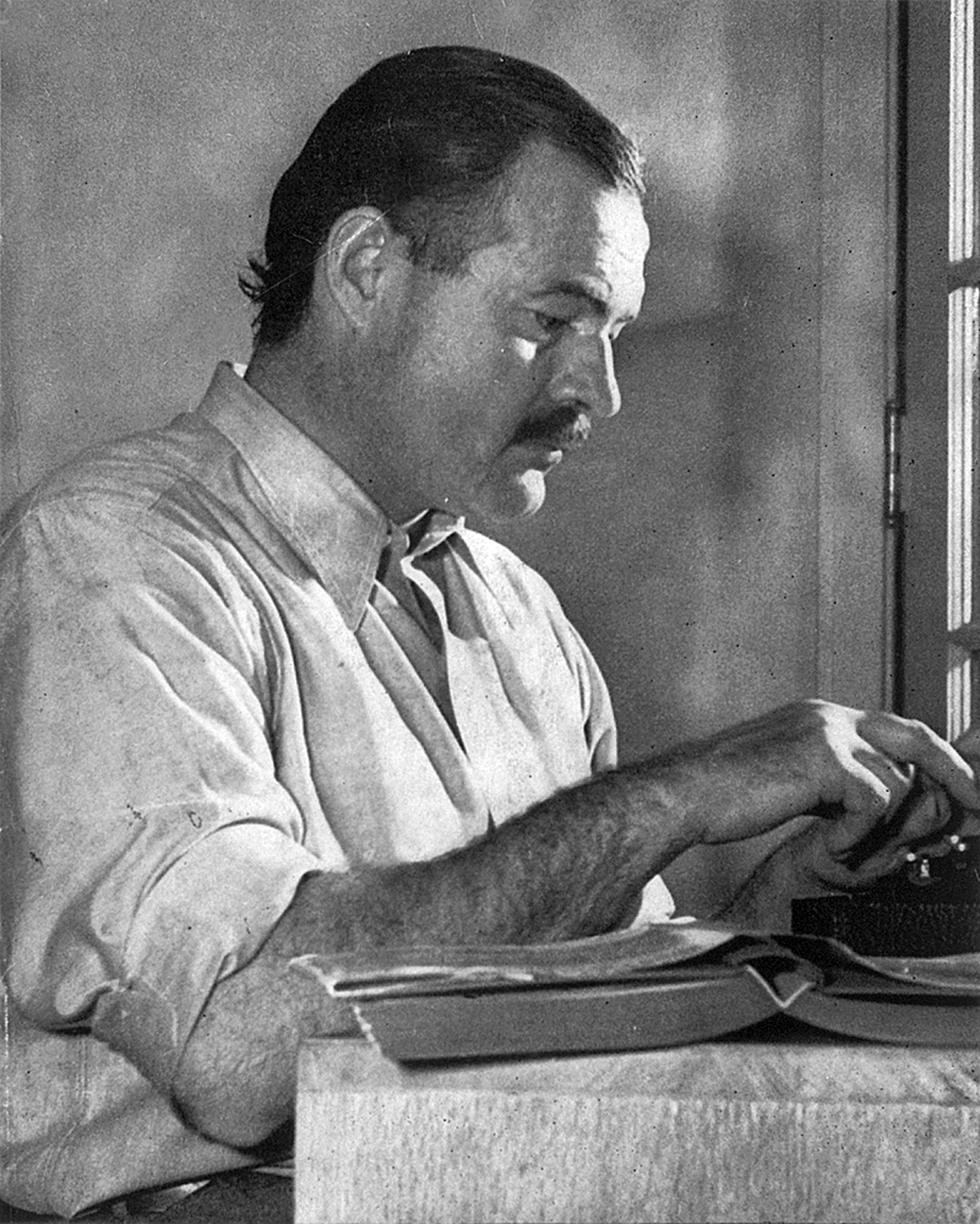

A Brief Overview of Hemingway’s Other Wives

Ernest Hemingway was married four times, with each marriage reflecting a different phase of his life and career. Before Gellhorn, Ernest Hemingway’s first wife was Hadley Richardson (1921-1927) and his second wife was Pauline Fife Pfeiffer (1927-1940). Richardson and Hemingway divorced, but not solely because of Ernest’s affair with Pfeiffer. Richardson and Pfeiffer played significant roles in Hemingway’s early literary career, with Richardson being a part of his life during his years in Paris as a young writer, and Pfeiffer during his rise to fame.

After his divorce from Gellhorn, Ernest fell for accomplished journalist Mary Welsh in 1946, who was with him until his death in 1961. According to Naomi Wood in an article for Pan MacMillan, Welsh actually referred to herself and the three other wives as “Graduates of ‘the Hemingway University’.”

While these marriages were important in Hemingway’s personal life, Gellhorn maintained her individuality and professional identity throughout her marriage to him, refusing to be overshadowed by his fame. Her career was a point of contention during their marriage and contributed to its dissolution.

Gellhorn’s Incredible Career as a War Correspondent

Martha Gellhorn’s career as a war correspondent began with the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). Her coverage of this conflict was notable for its direct and vivid narrative style, bringing the harsh realities of war to the forefront.

Gellhorn’s reporting from Spain was groundbreaking, not only for its content but also because she was one of the few female journalists covering the war. Her writings provided a unique perspective, focusing on the human aspect and the impact of the conflict on civilians, which was a departure from the traditional war reporting of the time.

World War II Reporting

Gellhorn’s reputation as a war correspondent was further established during World War II. She reported from various fronts, including Finland, Hong Kong, Burma, Singapore, and England. Her most notable achievement during this period was being one of the first journalists—and the only woman—to land at Normandy during the D-Day invasion in 1944. Gellhorn’s coverage of the war was characterized by her fearless approach and her ability to provide a personal touch to her reports, making the complexities of war more accessible to her readers.

Vietnam War Coverage

Do not ever let the bastards get you down.

Martha Gellhorn on the back of a postcard sent to John Pilger.

In the 1960s, Gellhorn turned her attention to the Vietnam War. Her reporting once again stood out for its focus on the human side of the conflict. She provided critical and unvarnished accounts of the impact of the war on both the soldiers and the Vietnamese population. Gellhorn’s reports from Vietnam were marked by her characteristic honesty and her unwillingness to shy away from the grim realities of war. Her work contributed significantly to the public understanding of the war and its consequences.

Throughout her career, Gellhorn’s contributions to war journalism were significant not only for the ground she broke as a female war correspondent but also for her unique approach to storytelling, which emphasized the human cost of conflict over political or military strategies. Her work remains a crucial part of war journalism history, offering insights into the role of journalists in shaping public perception of war.

Her Literary Achievements Beyond Journalism

Martha Gellhorn’s literary achievements extend beyond her renowned career in journalism. Her novels and short stories often delve into the themes of war, love, and human resilience. One of her notable novels, A Stricken Field (1940), is set against the backdrop of the German invasion of Czechoslovakia and is recognized for its poignant portrayal of the chaos and moral dilemmas of war.

The Wine of Astonishment (1948), another significant work, explores the personal and psychological impacts of World War II. Her fiction generally received critical acclaim for its insightful and empathetic exploration of complex human emotions and societal issues, often reflecting her experiences and observations as a war correspondent.

Influence of War Correspondence on Her Fiction

Gellhorn’s experiences as a war correspondent had a profound influence on her fiction writing. The firsthand accounts of conflict and human suffering she witnessed informed the realistic and often gritty portrayals in her novels. Her writing vividly captures the atmosphere of war-torn societies, the emotional turmoil of her characters, and the broader socio-political implications of conflict.

This direct influence is evident in works like The Face of War (1959), a collection of her war journalism, which blends her factual reporting with narrative techniques typical of her fictional works. Gellhorn’s unique ability to weave her war experiences into her fiction created stories that were not only engaging but also deeply resonant with the realities of the 20th century’s global conflicts.

Marth Gellhorn’s Impact and Legacy

In a memorial piece about the journalist and novelist for The New Yorker, Sam Knight quotes journalist John Pilger, who praised her work, saying that “‘There was never another Martha Gellhorn.’” Martha Gellhorn’s impact on journalism and literature is marked by her pioneering role as a female war correspondent and her distinct narrative style.

In journalism, she set a precedent for immersive, empathetic war reporting, focusing on the human aspect of conflicts. Her unflinching approach to covering wars, combined with her literary flair, brought a new depth to journalistic writing. In literature, her novels and short stories, often infused with themes drawn from her journalistic experiences, offered insightful commentary on the human condition amidst turmoil.

Gellhorn’s work challenged and expanded the boundaries of both journalism and fiction, blending them in a way that was both innovative and influential.

Legacy as a Female War Correspondent and Role Model

Martha Gellhorn’s legacy as one of the first female war correspondents is significant. She broke gender barriers in a field dominated by men, paving the way for future generations of women in journalism. Her courage, integrity, and commitment to reporting from the front lines served as an inspiration for many aspiring female journalists.

Gellhorn’s dedication to her craft and her ability to maintain her journalistic integrity in challenging environments have made her a role model for women in journalism and literature. She demonstrated that women could not only excel in this demanding field but also bring unique perspectives and insights.

Following in Gellhorn’s footsteps, several female war correspondents have made significant impacts in the field. These include Christiane Amanpour, Marie Colvin, and Lyse Doucet, among others. A prominent journalist known for her fearless reporting from war zones for CNN, Amanpour has covered major conflicts such as the Gulf War and the Bosnian War.

An American journalist who worked for the British newspaper The Sunday Times, Colvin was known for her reports from conflict zones including Chechnya, Kosovo, Sierra Leone, Zimbabwe, Sri Lanka, and Syria. She was killed in Syria in 2012 while covering the civil war. A Canadian journalist and BBC’s Chief International Correspondent, Doucet has reported from war zones across the Middle East, including Afghanistan and Syria, and is known for her in-depth analysis and human-focused stories.

These journalists have continued the legacy of courageous and insightful war reporting, often at great personal risk, and have contributed significantly to the field of journalism.

Martha Gellhorn vs. The Shadow of Hemingway

Martha Gellhorn’s marriage to Ernest Hemingway posed significant challenges, particularly regarding her professional identity. Despite her own considerable achievements as a journalist and author, Gellhorn often found herself overshadowed by Hemingway’s towering literary fame.

This was a source of frustration for her, as she was frequently referred to in the context of her husband’s career rather than for her own work. The public and media attention tended to focus more on her role as Hemingway’s wife rather than as an independent and accomplished journalist and writer in her own right.

Forging an Independent Identity and Reputation

Despite the challenges of being associated with Hemingway, Gellhorn steadfastly forged her own identity and reputation. She distinguished herself through her fearless war reporting and her distinct literary voice. Her dedication to covering major global conflicts and her unique perspective in her writings allowed her to build a reputation that stood on its own merits.

Gellhorn’s refusal to be a mere “footnote” in Hemingway’s life is well-documented; she insisted on her identity as a writer and journalist first and foremost. Her significant contributions to journalism and literature, particularly as one of the first female war correspondents, solidified her legacy as an influential figure independent of her marriage to Hemingway.

Design Dash

Join us in designing a life you love.

-

What is Tax-Loss Harvesting, Is It Legal, and Does It Build Wealth?

A legal and simple strategy, tax-loss harvesting helps you offset capital gains and grow your wealth by reducing your tax bill.

-

DesignDash Guide: Create the Ultimate Fall Capsule Wardrobe

Build a fall capsule wardrobe to streamline your style, save time, and support sustainability with versatile, high-quality pieces.

-

How to Support a Partner Who is Making a Major Career Change

Wondering how to be a supportive partner during periods of transition? Here’s how to care for your partner (and yourself) during this time.

-

How Dollar-Cost Averaging Can Help You Navigate Market Volatility

Learn how dollar-cost averaging (DCA) can help you grow your wealth with consistency and ease, even during market volatility.

-

Fall Meal Prep: Maximizing Space for Soups, Stews, and Bakes

From decluttering your pantry to creating a cozy prep station you’ll actually enjoy, here’s how to organize your kitchen for fall meal prep.

-

Looking to the Future? Maybe It’s Time to Refresh Your Firm’s Brand

Your interior design business shouldn’t have to rebrand every time you open a new studio or add a new service, but it might need a brand refresh.

-

What is Tax-Loss Harvesting, Is It Legal, and Does It Build Wealth?

A legal and simple strategy, tax-loss harvesting helps you offset capital gains and grow your wealth by reducing your tax bill.

-

DesignDash Guide: Create the Ultimate Fall Capsule Wardrobe

Build a fall capsule wardrobe to streamline your style, save time, and support sustainability with versatile, high-quality pieces.

-

How to Support a Partner Who is Making a Major Career Change

Wondering how to be a supportive partner during periods of transition? Here’s how to care for your partner (and yourself) during this time.

-

How Dollar-Cost Averaging Can Help You Navigate Market Volatility

Learn how dollar-cost averaging (DCA) can help you grow your wealth with consistency and ease, even during market volatility.

-

Fall Meal Prep: Maximizing Space for Soups, Stews, and Bakes

From decluttering your pantry to creating a cozy prep station you’ll actually enjoy, here’s how to organize your kitchen for fall meal prep.

-

Looking to the Future? Maybe It’s Time to Refresh Your Firm’s Brand

Your interior design business shouldn’t have to rebrand every time you open a new studio or add a new service, but it might need a brand refresh.