From Ichthyosaur to Squaloraja: Amazing Finds of Fossil Hunter Mary Anning

Summary

Reflection Questions

Journal Prompt

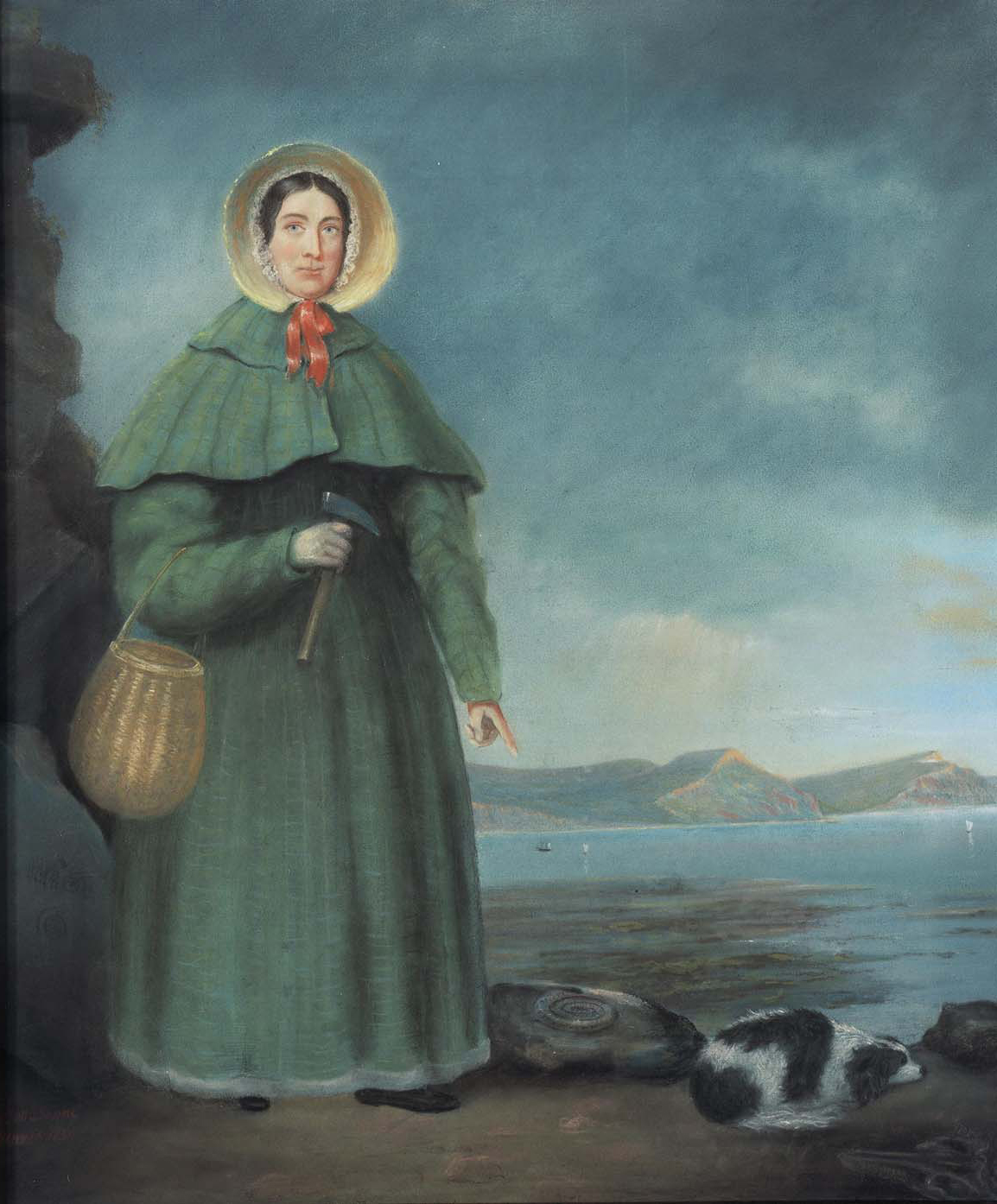

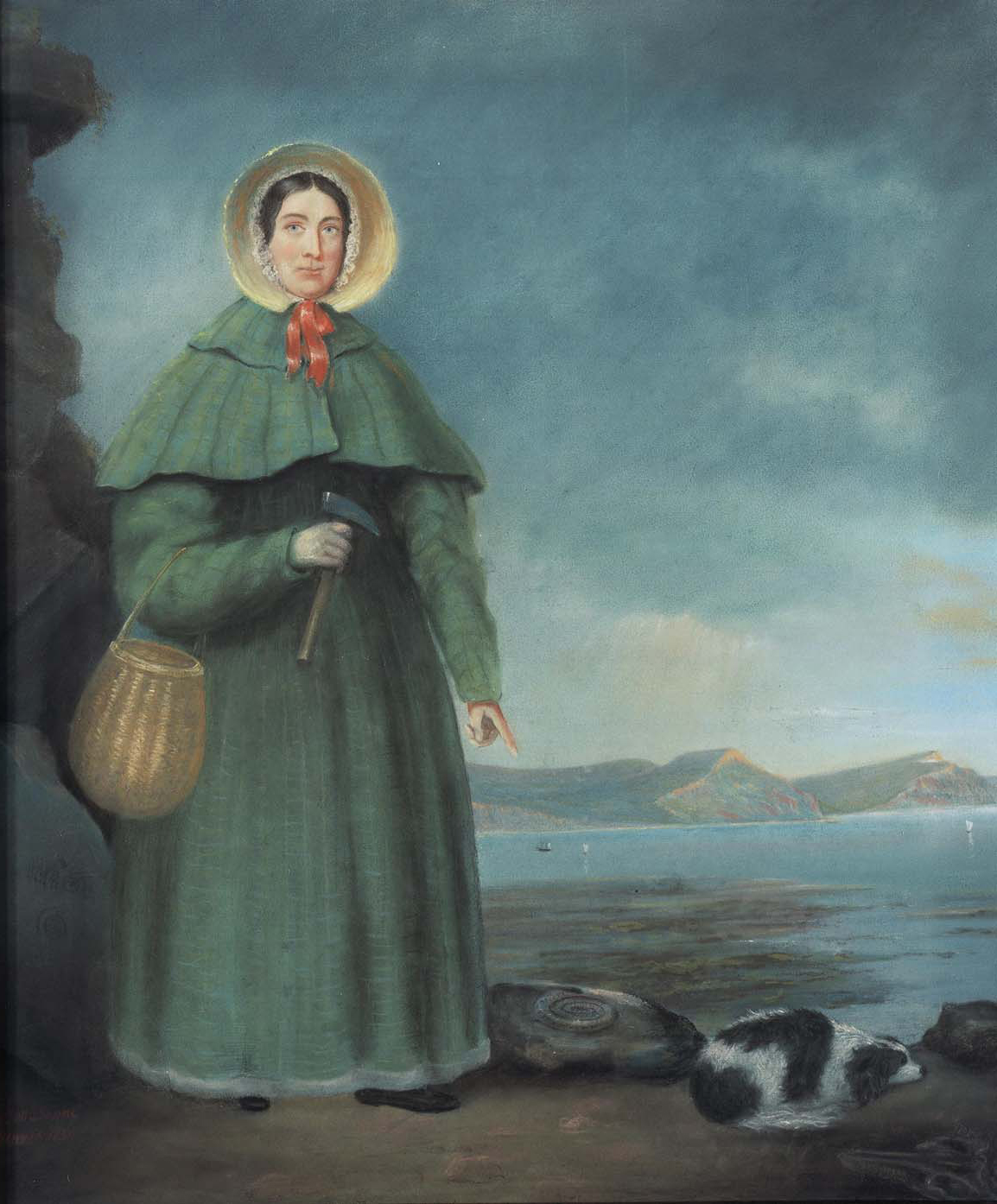

Mary Anning was a pioneering figure in paleontology, making groundbreaking discoveries that would shape the scientific understanding of prehistoric life for generations to come. Born into a modest family in Lyme Regis in 1799, Anning’s contributions were remarkable not only for their scientific value but also because they emerged during a time when the participation of women in the sciences was exceedingly rare.

Despite facing significant barriers due to her gender and social class, Anning’s keen eye for detail and her persistent dedication led to the discovery of several key fossil specimens, including the first complete Ichthyosaur skeleton. Her work provided critical evidence for the study of extinct species and helped lay the foundations for evolutionary theory. Anning’s legacy is a testament to the enduring impact an individual can have on a field, breaking through the constraints of her time to pave the way for future generations of scientists, especially women, in paleontology.

Read on to learn about her work. For more information about Mary Anning’s life of discovery, we encourage you to read the letters and accounts in Mary Anning’s Commonplace Book.

Mary Anning’s Beginnings

Mary Anning was born into the coastal charm of Lyme Regis, England in 1799 to mother Mary Moore and father Richard. This small seaside town, nestled along the Jurassic Coast, provided the backdrop for her early years. Growing up in Lyme Regis meant access to a treasure trove of prehistoric secrets just waiting to be uncovered. For young Mary, the cliffs and beaches were her first classrooms, offering lessons in a subject not yet fully appreciated by the world. It was here that she and Mary’s brother Joseph (both amateur fossil hunters) made their first discoveries.

The Anning family, though not wealthy, was rich in curiosity and a keen interest in the natural world. Mary’s father, Richard Anning, was a cabinetmaker and collector who supplemented the family’s income by selling fossils found in the local cliffs. These ‘curiosities’, as they were often called, became a family affair. It was from her father that Mary inherited not just a fascination with fossils but also the skills necessary to extract and clean them. This family enterprise laid the groundwork for Mary’s future discoveries.

How Lyme Regis Set the Stage for a Lifetime of Paleontological Exploration

Lyme Regis, with its dramatic cliffs and extensive fossil beds, is part of the Jurassic Coast, a World Heritage Site renowned for its geological wonders. The area’s rich deposits of marine fossils from the Jurassic period provided a fertile hunting ground for Mary.

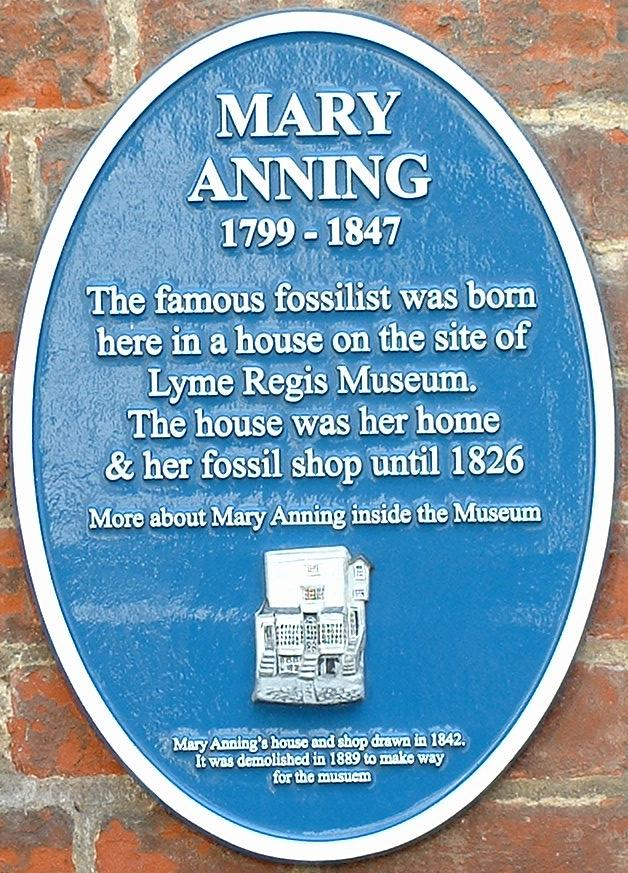

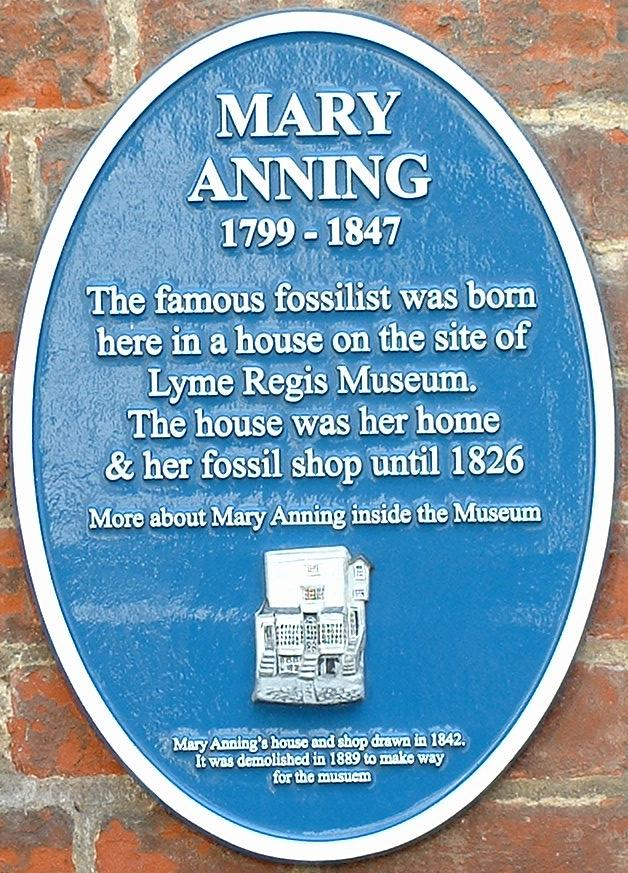

The constant erosion of the cliffs unveiled new finds, offering endless opportunities for discovery. For Anning, the unique geological features of Lyme Regis were both a playground and a research field, influencing her early interest and shaping her path as a fossil hunter. Today, the Lyme Regis Museum contains many records of Mary Anning’s discoveries, alongside those of other hunters who sought out the area.

The Path Toward Discovery for Mary Anning

The early 19th century was a period of curiosity, innovation, and upheaval. In the realm of science, it was a time when the boundaries of knowledge were expanding rapidly, yet society still clung to traditional beliefs and structures. The concept of extinct creatures and the deep time of Earth’s history were just beginning to take hold in the scientific community, challenging existing narratives. This era, ripe with discovery yet constrained by conventional thought, set the stage for Mary Anning’s remarkable contributions to paleontology.

Anning’s Self Education as a Woman in the 19th Century

Lacking formal education, which was a privilege few women could access at the time, Mary Anning was largely self-taught. She honed her skills through practice, observation, and an insatiable curiosity about the fossils she found in the cliffs of Lyme Regis.

Anning’s expertise was not just in finding these ancient relics; she also mastered the delicate art of extracting and preparing fossils for study, earning the respect of scientists and collectors alike. Her deep understanding of the geology and paleontology of her local area was gained through hands-on experience, making her one of the foremost fossil hunters of her time.

Finding the Ichthyosaur Skeleton in 1811

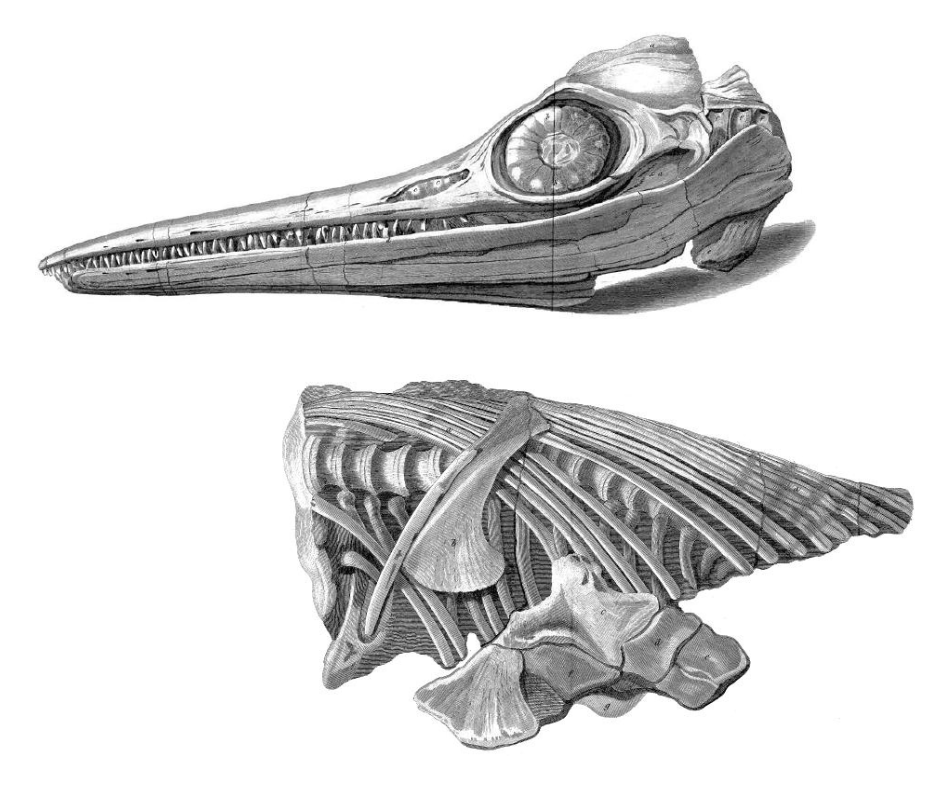

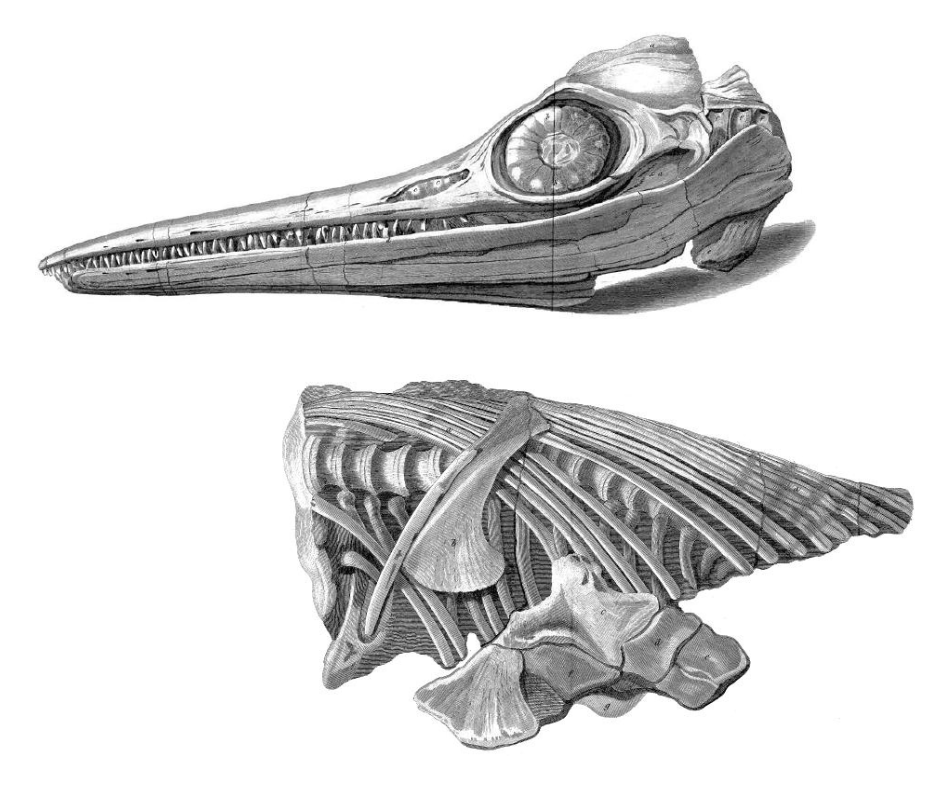

The discovery of the Ichthyosaur skeleton by Joseph and Mary Anning in 1811, when she was just 12 years old, was a turning point in paleontology. This was one of the first complete skeletons of an extinct reptile ever found, offering tangible evidence that creatures once roamed the Earth that no longer existed.

The Ichthyosaur, a marine reptile with a dolphin-like body and large, sharp eyes, captivated the scientific community and the public alike. Anning’s find was significant not only for its contribution to the understanding of prehistoric life but also for challenging existing perceptions about the history of the Earth and the creatures that inhabited it. This discovery marked the beginning of a series of finds by Anning that would continue to shape the field of paleontology.

Just one year later in 1812, Mary found the torso of the same skeleton.

Anning’s Major Discoveries and Contributions

Discovery of the First Complete Plesiosaur Skeleton in 1823

In 1823, Mary Anning unearthed a fossil that would once again stir the scientific community — the first complete Plesiosaur skeleton. With its long neck, small head, and flippers, this discovery challenged existing notions of what prehistoric marine life looked like.

The Plesiosaur find was pivotal, as it provided a clearer picture of the diversity of life in ancient seas and lent further credence to the concept of extinction. Anning’s meticulous work in extracting and preparing the skeleton allowed for detailed study, solidifying her reputation as a skilled fossil hunter and contributing significantly to the body of knowledge in paleontology.

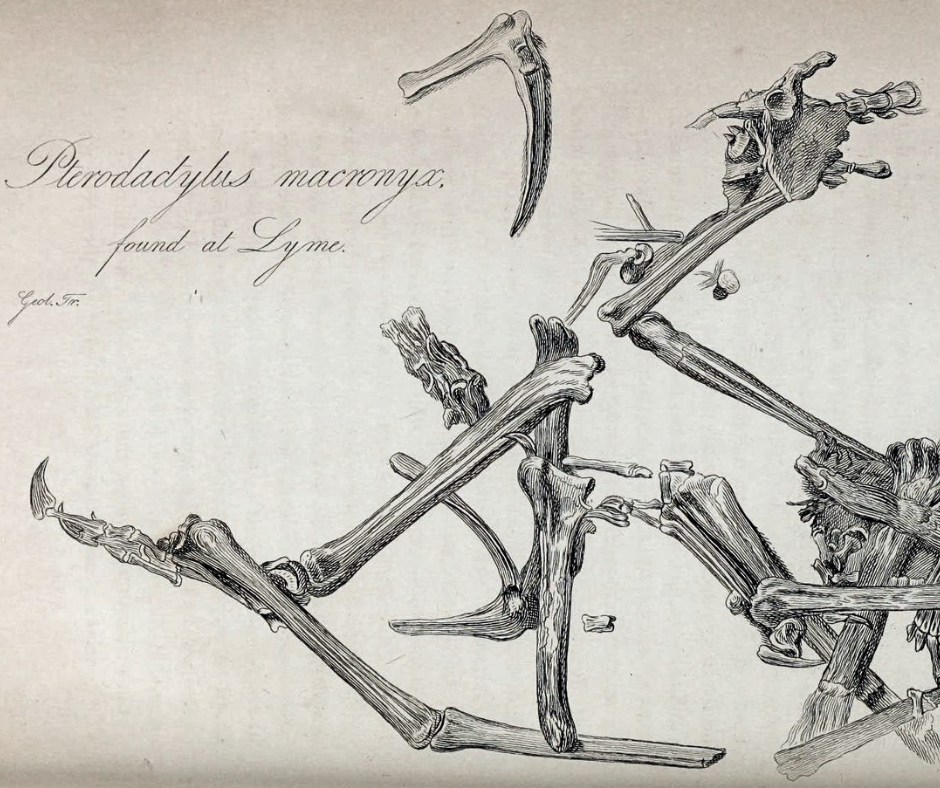

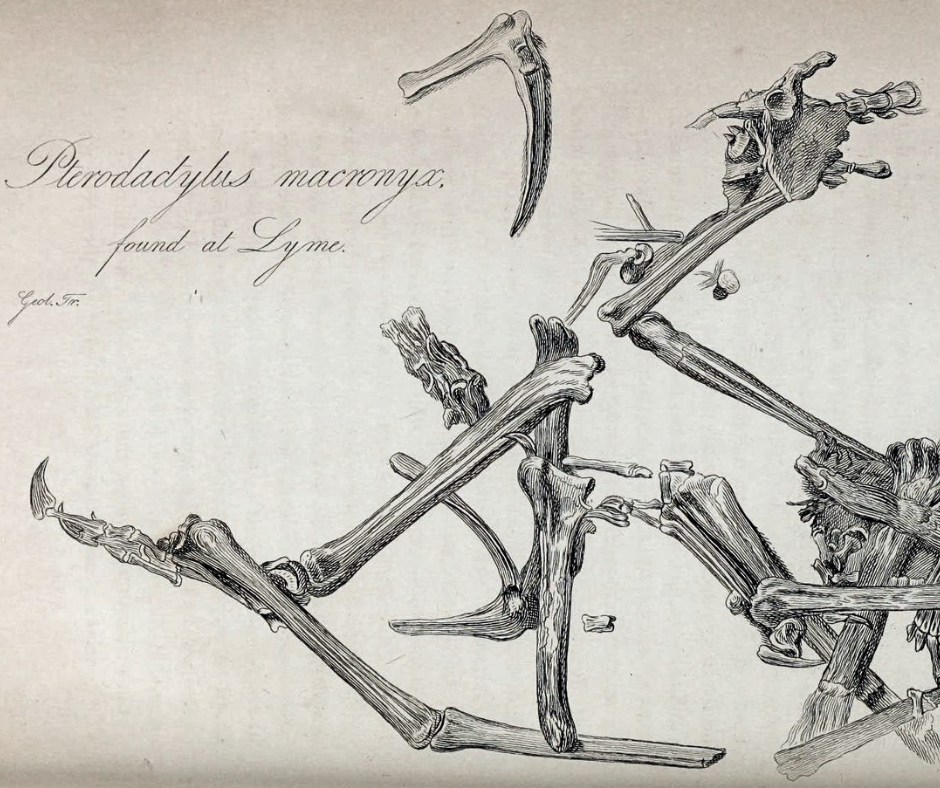

Finding of the first British Pterosaur in 1828

The year 1828 saw Mary Anning add another feather to her cap with the discovery of the first British Pterosaur, a find that represented the first known example of these flying reptiles outside Germany. This discovery was particularly significant because it expanded the geographical understanding of Pterosaur habitation, indicating these creatures once soared above much of the ancient world. The Pterosaur find not only added a new dimension to the diversity of prehistoric life but also highlighted the global nature of paleontological evidence, showcasing Anning’s role in broadening the scientific horizon.

A Review of Mary Anning’s Many Discoveries

Mary Anning discoveries in the early 19th century were pivotal in the field of paleontology and significantly contributed to the scientific understanding of prehistoric life. Mary Anning’s fossil finds were instrumental in the development of paleontology as a scientific discipline.

They not only expanded the knowledge of extinct species but also contributed to the understanding of evolutionary theory and the history of life on Earth. Anning’s work laid the groundwork for future generations of paleontologists, and her findings are still studied and revered in the scientific community today. While many of her fossil remains are now housed in the Natural History Museum in London and the Dorset County Museum, some occasionally go on loan to other museums across the world.

Below are some of the most notable species this fossil collector discovered.

Ichthyosaur

One of Anning’s first major discoveries, made when she was just twelve years old, was the skeleton of an Ichthyosaur in 1811. Ichthyosaurs were marine reptiles that lived during the time of the dinosaurs. The specimen she found was one of the first complete skeletons to be uncovered, providing invaluable insights into these ancient creatures.

Plesiosaur

In 1823, Anning discovered the first complete Plesiosaur skeleton. Plesiosaurs were another type of marine reptile with long necks and small heads, distinct from the Ichthyosaurs. This discovery was significant because it challenged existing scientific notions about the morphology and diversity of prehistoric marine life.

Pterosaur

In 1828, Anning uncovered the first Pterosaur skeleton identified outside of Germany, and it was the first to be found in Britain. Pterosaurs were flying reptiles, not dinosaurs, but lived during the same period. This find was crucial in understanding the diversity and global distribution of Pterosaurs.

Squaloraja

Although not as well-publicized as her other discoveries, Anning also found fossilized remains of Squaloraja, a fish closely related to both sharks and rays, which provided insights into the evolutionary history of these species.

Coprolites

Among Mary Anning’s contributions to paleontology was her insight into the nature of coprolites, or fossilized feces. Initially, the significance of these peculiar stones was not fully understood. Anning’s observations and collections helped scientists realize that coprolites were the fossilized remains of ancient animal feces, offering an invaluable window into the diet and ecosystem of extinct species.

This understanding was crucial for reconstructing past environments and food chains, demonstrating Anning’s role in developing paleontology as a comprehensive science that not only studies the bones of ancient creatures but also their lives and habitats.

Challenges She Faced as a Female Fossil Hunter

Mary Anning’s journey was not just about discovering fossils; it was also a constant battle against the gender and social class barriers of her time. In the early 19th century, geology and the broader scientific community were firmly male-dominated realms, where women, especially those from working-class backgrounds like Anning, were often sidelined.

Despite her significant contributions to paleontology, Anning faced an uphill battle for recognition and respect. Her insights and discoveries were frequently appropriated by male scientists without proper credit, reflecting the gender biases that pervaded society. Yet, Anning persevered, relying on her expertise and the quality of her work to carve a space for herself in the annals of science.

Financial Struggles

Economic hardship was a constant in Mary Anning’s life, shaping her path and her pursuits. The Anning family’s financial situation was precarious, and the death of her father left them in debt. Fossil hunting, which began as a necessity to supplement the family’s income, turned into Anning’s lifeline.

She opened a fossil shop in Lyme Regis, which became a center for collectors and scientists interested in her finds. This shop was not just a source of income; it was a hub of scientific inquiry and exchange. Through her entrepreneurial spirit, Anning managed to sustain her family and fund her fossil hunting expeditions, all while contributing to the scientific community.

Annuity Granted by the British Association for the Advancement of Science and the Geological Society of London

Later in Mary Anning’s life, she received a measure of financial security through an annuity, which was essentially a subscription fund set up by members of the British scientific community to support her. Recognizing her contributions to paleontology and the financial difficulties she faced, this annuity was established in 1838 by the British Association for the Advancement of Science and the Geological Society of London, among others.

The establishment of this annuity acknowledged not only the scientific value of Anning’s discoveries but also the challenges she had faced in a field that was not welcoming to women, particularly those of her social standing. This financial support allowed her a degree of stability and recognition, albeit late in her career. It was a rare gesture of support from the scientific community, which, during her lifetime, often overlooked her contributions and failed to fully recognize her due to the prevailing gender biases and societal norms.

The annuity is significant because it represents one of the few formal recognitions of Anning’s contributions to science during her lifetime. It also highlights the beginning of a slow change in how the contributions of women and non-academic scientists were viewed in the scientific community. Despite this support, Anning continued to face financial challenges, but the annuity helped her continue her work in paleontology until her death in 1847.

Lack of Formal Recognition During Her Lifetime

Despite her groundbreaking discoveries and contributions to the field of paleontology, Mary Anning received little formal recognition from the scientific community during her lifetime. The societal norms and scientific institutions of the day often excluded women, and Anning’s working-class background further compounded her invisibility.

Still, she forged significant relationships with many of the leading geologists and paleontologists of her era. These scientific luminaries often visited Lyme Regis to buy fossils from her and discuss paleontological theories. Figures like Henry De la Beche, William Buckland, and Richard Owen, among others, valued her expertise and often sought her insights.

Anning’s informal network was a testament to her deep knowledge and the respect she commanded among her peers. These relationships were complex, marked by both genuine collaboration and the challenges of navigating a field that often failed to fully acknowledge her contributions. Though she equaled each of these figures, only Mary was left out of public conversations.

Unfortunately, many of her finds were published under the names of male scientists, leaving her contributions largely unacknowledged. It wasn’t until long after her death that Anning’s pivotal role in the development of paleontology was fully recognized and celebrated. Her story highlights the challenges faced by women in science, serving as a poignant reminder of the need for inclusivity and recognition in the scientific community.

Final Thoughts on Mary Anning’s Legacy as a Pioneer of Paleontology

Mary Anning’s story is a testament to the enduring power of curiosity and perseverance against the odds. Though her contributions to paleontology were not fully recognized during her lifetime, the legacy of her discoveries has continued to inspire and influence generations of scientists long after her passing in 1847. Anning’s work laid foundational stones in the field of paleontology, significantly advancing the understanding of prehistoric life and contributing to the development of evolutionary theory.

Today, her impact is celebrated through memorials, museums, and exhibits in Lyme Regis and beyond, including the Lyme Regis Museum located on the site of her former home and shop. Modern acknowledgments of her contributions, such as the Royal Society naming her among the ten most influential British women in the history of science, reflect a growing appreciation for her work.

Reflecting on Anning’s story highlights the importance of recognizing and valuing the contributions of pioneers, particularly those who, like Anning, overcame significant barriers to enrich our understanding of the natural world. Her legacy serves as a powerful reminder of the contributions women have made—and continue to make—to science, urging us to ensure they are remembered and celebrated within the annals of scientific history.