Miniature Marvels: Art & Architecture of Ancient Egyptian Models

Summary

Reflection Questions

Journal Prompt

The ancient Egyptians were masterful designers, and their creation of models was certainly no exception. These miniature marvels played an important role in their culture. Today, they offer us profound insights into their daily lives, religious beliefs, and afterlife practices. From intricate boat models intended to transport the deceased to the afterlife to detailed household scenes ensuring comfort beyond death, these models intertwined the practical and spiritual. By exploring various types of models—funerary, architectural, and artistic—we gain a deeper understanding of how the Egyptians viewed life and the afterlife, as well as their advanced craftsmanship and attention to detail.

Exploring the Origins of Ancient Egyptian Models

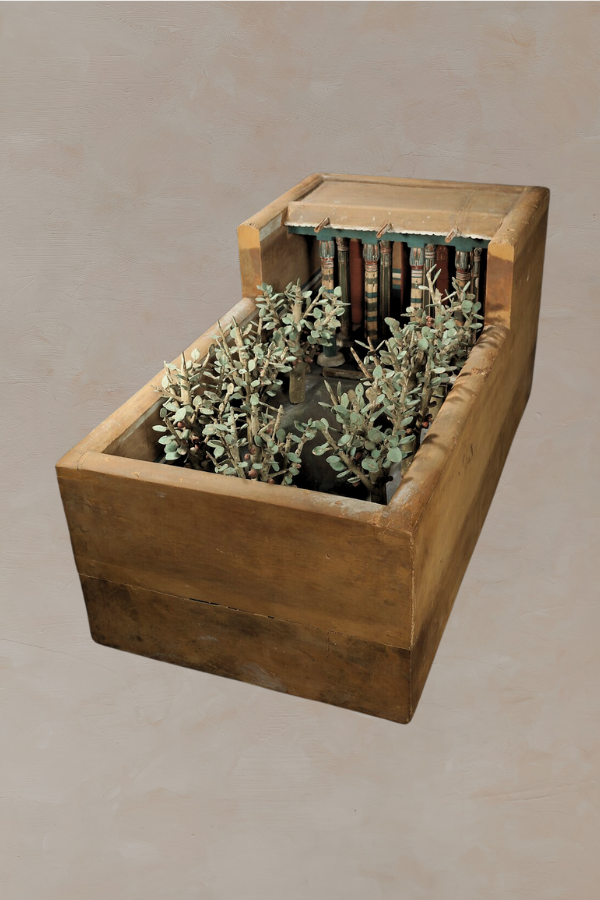

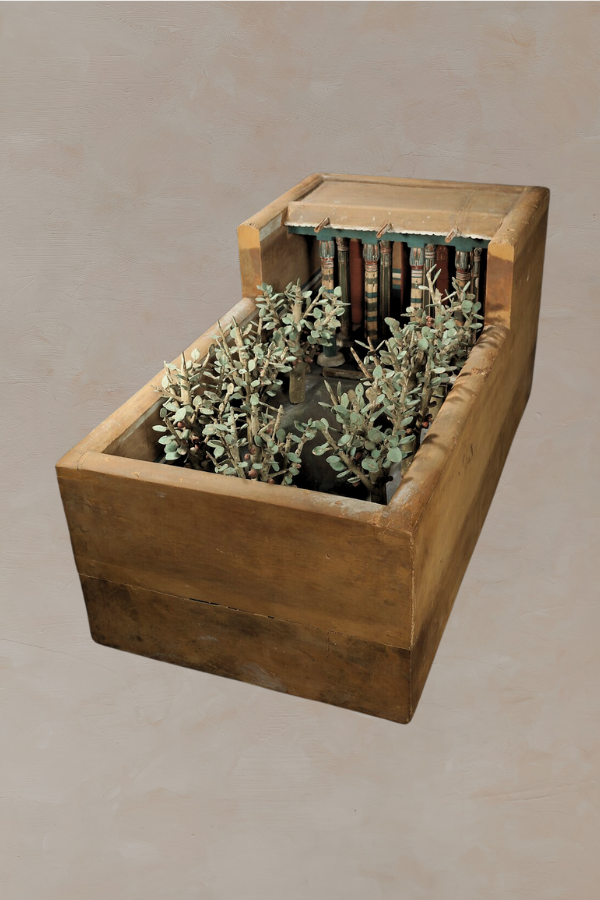

Model of a Granary with Scribes, Middle Kingdom, ca. 1981–1975 B.C., on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The ancient Egyptians created models for several interrelated purposes, primarily centered around their religious beliefs and practices associated with the afterlife. These models were intended to ensure that the deceased had everything they needed to sustain themselves in the next world. This practice reflects the Egyptian concept of the afterlife as a continuation of earthly life, where the dead would require food, tools, transportation, and companionship, just as they did while living.

The use of models in tombs began as early as the Predynastic and Early Dynastic Periods (c. 3900–2680 BCE), where they primarily included boats, granaries, and offering objects made from clay and ivory. The practice became more elaborate during the Old Kingdom (c. 2680–2180 BCE) with stone statuettes of individuals performing specific activities. By the Middle Kingdom (c. 2055–1650 BCE), this tradition reached its zenith, with a wide variety of wooden models depicting detailed scenes of daily life, such as baking, brewing, and other household activities. These models served as magical substitutes to ensure that the depicted provisions and activities would continue in the afterlife.

Evolution of Model Design and Execution

Model of a River Boat, Middle Kingdom, mid-Dynasty 12, about 1875 BCE, Egyptian; Meir, Egypt

From the Middle Kingdom, notable examples include the models found in the tomb of Meketre, which contained scenes of agricultural activities, crafts, and domestic chores, demonstrating the Egyptians’ meticulous attention to detail and their advanced woodworking skills. These models are invaluable for understanding ancient Egyptian life and beliefs because they provide a snapshot of daily activities and social structures that textual sources alone cannot fully convey.

The practice continued into the New Kingdom (c. 1550–1070 BCE), although there was a shift towards more integrated tomb art and larger-scale representations. The models from these periods are among the most complete and detailed, often found in the tombs of high officials and elites, underscoring their importance in ensuring a well-provided afterlife for the deceased.

Ancient Egyptian Funerary Models

Boat Models

Boat models were a significant part of ancient Egyptian tombs, symbolizing the deceased’s journey to the afterlife. These models ranged from simple canoes to elaborate solar boats, reflecting their use in both mundane and sacred contexts. Solar boats were believed to transport the souls of the deceased alongside the sun god Ra in his daily journey across the sky.

Model Sailing Boat Transporting a Mummy, Middle Kingdom, ca. 1900–1885 B.C., On view at The Met Fifth Avenue in Gallery 109

Funerary boats, on the other hand, were often depicted carrying the mummified body of the deceased across the Nile to their burial site. These models underscored the importance of boats in Egyptian mythology and daily life, serving as a metaphor for the transition from life to the afterlife and ensuring safe passage for the deceased’s spirit. As this resource from the Art Institute of Chicago explains, model boats were often “placed in a tomb chamber to ensure that the deceased would be able to travel for eternity.”

Household Models

Model of a House, Middle Kingdom, ca. 1750–1700 B.C.

Household models were essential in ensuring the deceased’s comfort and sustenance in the afterlife, reflecting the Egyptian belief that life continued beyond death. These models often depicted detailed scenes of everyday life, including houses, gardens, granaries, and workshops.

Common activities portrayed included baking, brewing, and grain storage, representing the basic necessities that the deceased would need to maintain their lifestyle in the afterlife. By including these miniature replicas in their tombs, Egyptians aimed to provide for all aspects of the deceased’s daily needs, ensuring a smooth transition to the next world and perpetual comfort.

Offering Models

Model Bakery and Brewery from the Tomb of Meketre, Middle Kingdom, ca. 1981–1975 B.C.

Offering models played a crucial role in providing sustenance for the deceased in the afterlife. These models depicted a variety of food items and beverages, ensuring that the deceased would not go hungry in the next world.

Common items included loaves of bread, cuts of meat, and jars of wine or beer, all essential components of the Egyptian diet. The inclusion of these offerings was rooted in the belief that the deceased would need continuous nourishment, and the models served as magical substitutes that would become real in the afterlife through rituals and spells.

This practice highlights the Egyptians’ deep concern for the well-being of their loved ones even after death, ensuring that they were well-fed and cared for in their eternal journey.

Architectural Models

Sphinx of Amenhotep III, possibly from a Model of a Temple, New Kingdom, ca. 1390–1352 B.C.

Temple models were small-scale replicas used in various religious rituals and offerings, reflecting the Egyptians’ dedication to their gods and the importance of temple architecture in their religious life. These models meticulously showcased the intricate details of temple architecture, including columns, sanctuaries, and statues of deities, providing a miniature yet comprehensive representation of the grand temples.

Fuel your creative fire & be a part of a supportive community that values how you love to live.

subscribe to our newsletter

The religious significance of these models was profound, as they were believed to serve as abodes for the gods during rituals and ceremonies, allowing the divine presence to be accessible to the people. By including these models in their offerings, Egyptians sought to gain favor from the gods and ensure their protection and blessings in both life and death.

Miniature pyramid models were often used as amulets or in religious practices, symbolizing the monumental tombs built for pharaohs and elites. These models, crafted from various materials such as stone, clay, or precious metals, served not only as representations of the grandeur and significance of the pyramids but also as protective charms.

They were believed to embody the power and stability of the pyramids, ensuring the eternal preservation and protection of the deceased’s soul. The use of these models in religious contexts highlights their role in rituals aimed at securing a safe passage to the afterlife and safeguarding the tombs from malevolent forces. These miniature pyramids encapsulated the essence of the larger structures, reflecting their importance in ancient Egyptian burial practices and their enduring legacy as symbols of royal and elite power.

Art and Sculpture Models

Model figure, Middle Kingdom, ca. 1981–1640 B.C.

The crafting of small statues and figurines was a prominent art form in ancient Egypt, reflecting the society’s religious beliefs and social hierarchy. These models often depicted gods, goddesses, and individuals, serving as intermediaries between the divine and the mortal worlds. The statues of deities were crafted with meticulous detail and placed in temples and homes to ensure divine protection and favor.

Human figurines, on the other hand, represented the deceased and their family members, placed in tombs to accompany and serve the deceased in the afterlife. These statues and figurines were not mere decorative objects; they were imbued with spiritual significance, intended to provide a tangible presence of the divine and the deceased in religious and funerary contexts..

Canopic Jar Models

Canopic Jar of Ruiu, New Kingdom, ca. 1504–1447 B.C.

Canopic jars were essential components of the mummification process, designed to hold the internal organs of the deceased, which were removed during embalming. Each jar was dedicated to one of the four sons of Horus—Imsety, Hapi, Duamutef, and Qebehsenuef—who protected the liver, lungs, stomach, and intestines, respectively. The jars typically featured lids shaped like the heads of these deities, symbolizing their protective roles.

The preservation of the body, including the internal organs, was crucial for ensuring the deceased’s rebirth and well-being in the afterlife. The canopic jars were placed in tombs alongside the mummified body, underscoring the Egyptians’ meticulous care in preparing for the afterlife and their belief in the protective power of the gods.

Ritual Models

Ritual models—like the Opening of the Mouth model pictured above—were also common. The “Opening of the Mouth” ritual was one of the most important ceremonies in ancient Egyptian funerary practices, aimed at restoring the senses of the deceased so they could enjoy the afterlife. Models representing the equipment used in this ritual were crafted with great care and detail during the Old Kingdom (ca. 2465–2150 B.C.). These models typically included a variety of tools, such as adzes, pesesh-kef implements, and other ceremonial instruments, often made from wood, stone, or metal.

The significance of these models lay in their role in ensuring the ritual’s efficacy even after death, symbolizing the continuation of life and the reactivation of the deceased’s faculties. By including these models in tombs, ancient Egyptians sought to guarantee that the necessary rituals could be performed eternally, thus securing the deceased’s successful transition to the afterlife and their ability to interact with the world of the living.

Final Thoughts on Ancient Egyptian Models

Model of a procession of offering bearers, Middle Kingdom, ca. 1981–1975 B.C.

These models, spanning from funerary boats and household scenes to temple replicas and ritual equipment, encapsulate the Egyptians’ profound beliefs in the afterlife and their meticulous preparations for it. Through these miniature representations, we gain invaluable insights into their daily activities, religious practices, and the advanced level of craftsmanship they achieved.

The models not only served practical and spiritual purposes in their time but also continue to educate and fascinate modern scholars and enthusiasts. They bridge the gap between the ancient and contemporary worlds, allowing us to glimpse the rich cultural heritage and enduring legacy of ancient Egypt. As we continue to explore and study these intricate artifacts, we deepen our appreciation for the complexity and sophistication of one of history’s greatest civilizations.