Matisse, Derain, and Dufy: Painters of the Fauvist Movement

Summary

Reflection Questions

Journal Prompt

The Fauvist movement—emerging at the dawn of the 20th century between 1905 and 1910—marked a pivotal shift in the trajectory of modern art. Deriving its name from the French term “les fauves”—translated as “the wild beasts”—Fauvism was characterized by its audacious and often non-representational use of bold, bright colors. Rather than adhering to the traditional and descriptive roles of color, Fauvist artists harnessed it as an independent medium of expression—prioritizing emotion and abstraction. In the broader context of modern art, Fauvism—though very brief—played an instrumental role in challenging prevailing artistic norms and paved the way for subsequent avant-garde movements that further explored the emotive potential of form and hue. Some consider this period in art history a bridge between Post-Impressionism, Edvard Munch’s Primitivism, and later Expressionist movements. From Henri Matisse to André Derain, let’s explore the Fauvist paintings and philosophy of this movement’s founding artists.

The Fauvist Movement

The Fauvist movement was characterized by its bold, undiluted, and often unconventional use of color. As noted above, the word “Fauvism” is derived from the French term “les fauves”—which means “the wild beasts.” This name was coined by art critic Louis Vauxcelles during the annual Salon d’Automne exhibition in Paris in 1905. It was used somewhat derisively to describe the works of a group of artists whose paintings were marked by an unusual degree of abstraction and vibrant color.

Unlike its contemporary movements, Fauvism was not bound by a strict philosophy. The primary unifying feature among the Fauvist painters was their mutual interest in using color as an emotional force—often divorced from its descriptive, representational purpose. Thus, trees could be painted red and skies green if it served the artist’s expressive intent.

Inspirations and Influences

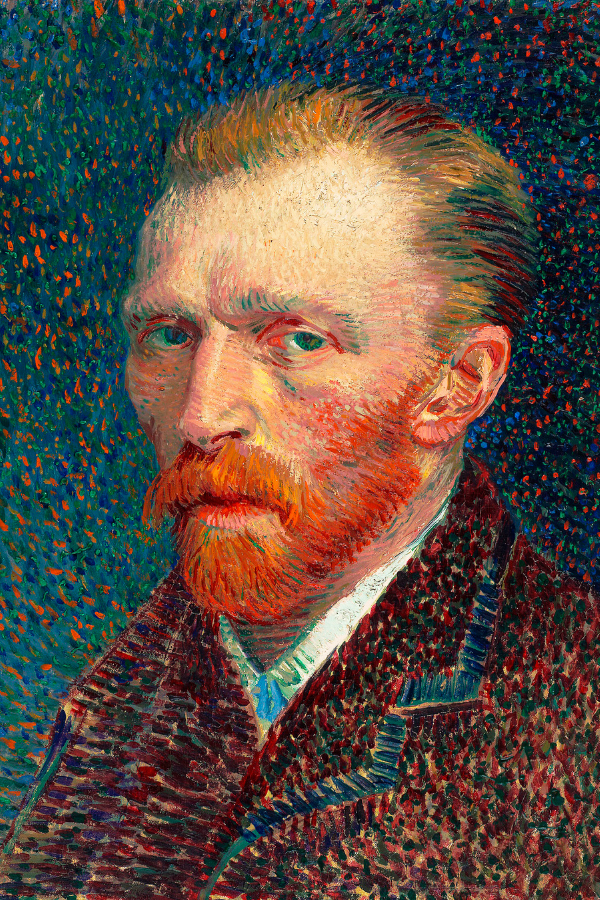

Fauvism was directly influenced by several earlier artists who heralded a departure from traditional artistic conventions. One profound influence was the Post-Impressionist work of Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin.

Van Gogh’s vivid color choices—employed not merely for representational fidelity but to convey emotional intensity—resonated with the Fauvists’ aspirations. Gauguin’s experiences in Tahiti led him to produce works that prioritized emotion and symbolism over realism—using color in an abstract, symbolic manner. These Post-Impressionist tendencies encouraged artists to explore color’s potential beyond mere imitation.

In tandem with the Post-Impressionists, the Neo-Impressionist techniques—particularly Pointillism as practiced by Georges Seurat and Paul Signac—were instrumental in shaping Fauvist aesthetics. The Neo-Impressionists’ scientific approach to color—which involved juxtaposing small dots of pure pigment to create vibrancy and luminosity—offered the Fauvists insights into the mechanics of color interaction.

While Fauvism did not adopt the methodical rigor of Pointillism, it assimilated the core idea that color—when liberated from its descriptive duties—could serve as a potent tool for emotional and expressive ends.

Exploring the Influence of African Art on Fauvism

Fauvist art—like several other early twentieth-century art movements—was influenced by African artwork and cultural items, primarily in its emphasis on abstraction, and direct expression. The early 20th century saw a burgeoning interest in “primitive” or non-Western art among European avant-garde artists. African masks and sculptures were especially sought after and admired for their powerful, abstracted forms and their emotive qualities.

Henri Matisse—a leading figure of the Fauvist movement—was among the many artists of the time who were intrigued by the aesthetics of African art. He—along with other artists like Pablo Picasso—began collecting African sculpture and masks. Henri Matisse and others incorporated the principles of abstraction and simplification found in these artifacts into their own works.

However, it’s important to approach this influence with nuance. While Fauve artists did draw inspiration from the forms and aesthetics of African art, they did not typically honor the cultural or contextual significance of these artifacts. The appropriation was largely aesthetic—a feature that has become the subject of criticism and analysis in postcolonial art discourse. Fauvist artists were drawn to the visual qualities of African art—seeing in it a kind of raw, unmediated expression that aligned well with their own quest to break away from the refined, naturalistic traditions of European art.

It’s also worth noting that African art was not the only non-Western influence on Fauvism. The movement was part of a broader context in which artists were looking beyond Europe for inspiration—exploring artifacts from Oceania, the indigenous cultures of the Americas, and other sources to fuel their artistic innovations.

Challenges Carving Out Space in Paris’ 20th Century Art Scene

The official Paris Salon—with its long history as the premier art exhibition in France—was traditionally conservative in its tastes. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Salon had become increasingly resistant to new and avant-garde art forms—favoring more academic and traditional styles.

The Fauvist style—with its radical approach to color, form, and spontaneous brushwork—was quite avant-garde for its time. Such bold and non-representational use of color by Fauvist artists was a stark departure from the naturalistic and classical tendencies favored by the official Salon.

Consequently, Fauve paintings and their creators found it challenging to gain acceptance or favorable placement within the official Paris Salon during the movement’s peak years.

Creating Their Own Space for Fauvism Art

This resistance to new artistic forms by the official Salon was a driving force behind the establishment of alternative exhibition venues—such as the Salon des Indépendants and the Salon d’Automne. These alternative salons offered avant-garde artists—including the Fauvists—an opportunity to showcase their works without the constraints of the official Salon’s conservative jury.

The Salon d’Automne was established in 1903 in Paris as an alternative to the official Paris Salon. The official Salon had—for years—been the primary venue for artists to exhibit their work. However, its conservative tastes often left avant-garde and innovative artists out in the cold—prompting the need for alternative platforms. The Salon d’Automne was established by artists and intellectuals—including the architect Frantz Jourdain—with a vision to create an exhibition that embraced contemporary artistic currents, allowing for a more inclusive and progressive presentation of art.

Much like the Salon des Indépendants—which was established earlier in 1884 and also acted as a counter to the official Salon—the Salon d’Automne was crucial in promoting new and avant-garde art movements. Both Salons provided artists with the freedom to experiment and break from traditional artistic conventions, making them pivotal platforms for emerging styles.

The 1905 Salon d’Automne Exhibition

In the context of the Fauvist movement, it was the 1905 exhibition at the Salon d’Automne that proved a defining moment. Henri Matisse, André Derain, and other artists exhibited works that shocked the art world with their radical use of undiluted, non-representational color. It was in response to the intense coloration of these paintings that art critic Louis Vauxcelles famously described these artists as “fauves” or “wild beasts.”

While both the Salon des Indépendants and the Salon d’Automne were instrumental in the development and promotion of Fauvist art, it was the latter that played the most direct role in its christening. The unjuried, open nature of these exhibitions provided the Fauvists with the freedom to display their pioneering works without the constraints of traditionalist aesthetics—enabling them to push existing boundaries of artistic expression and lay the foundation for modernist art movements that followed.

Of course, the official Paris Salon did evolve over time. As the twentieth century progressed—and especially after World War I—the Salon’s stance towards modern art began to soften. It became more accepting of newer art movements. Still, alternative salons were more conducive venues for Fauvist exhibitions.

Influential Fauvist Artists

While Henri Matisse, André Derain, and Maurice de Vlaminck founded the Fauvist movement, other artists like Georges Braque, Othon Friesz, and Albert Marquet dabbled in the bold and emotional style. Let’s take a closer look at the founders of Fauvism, as well as the work of a few like-minded artists who drew significant inspiration from their paintings and philosophies.

Georges Braque (1882-1963)

While Braque had a Fauvist phase, the artist is best known for pioneering Cubism—partially in parallel to rather than in complete concert with Picasso. Still, Braque dabbled in Fauvism. As the youngest in a group of Fauvist artists, Braque collaborated with Dufy and others. It was during his Fauvist period that Braque began developing his Cubist ideas, later meeting Pablo Picasso in 1907.

Perhaps his most notable Fauvist painting is the oil on canvas entitled Large Trees Under the Jas de Bouffan—created in 1906. Other works by Braque were exhibited at the Salons des Indépendants and d’Automne.

Henri Matisse (1869-1954)

Often regarded as the primary figure in Fauvism, Matisse’s works like The Joy of Life, Woman with a Hat, and The Green Line or Portrait of Madame Matisse are iconic representations of the movement. His use of non-naturalistic colors and relaxed brushwork showcased his belief in color as the foundation of his artistic expression. Of course, Henri Matisse exhibited at the at the 1905 d’Automne Salon and other important early Fauvist shows.

In an essay for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Magdalena Dabrowski notes that Matisse’s influence on Modern art cannot be understated. According to Dabrowski, Matisse’s “stylistic innovations…fundamentally altered the course of modern art and affected the art of several generations of younger painters.”

While Matisse had significant interactions with many artists of his time, his collaboration with André Derain was particularly notable. Both spent a summer in 1905 in Collioure—producing artworks that became foundational for Fauvism.

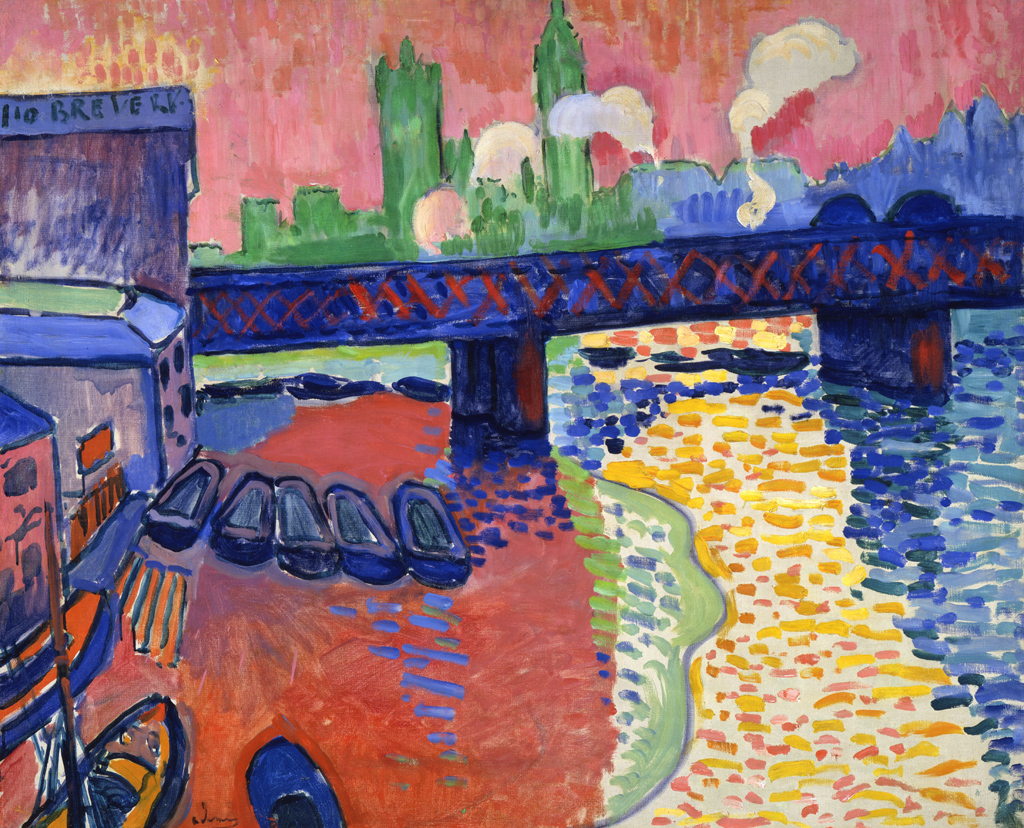

André Derain (1880-1954)

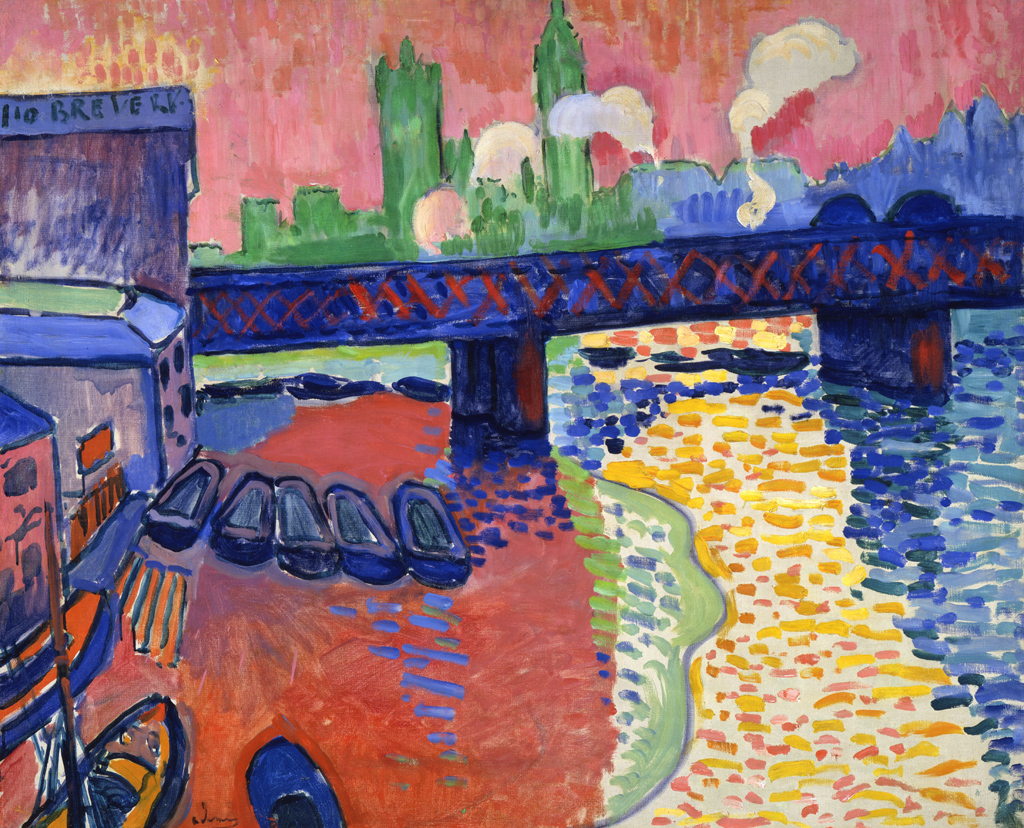

Another central figure in the Fauvist movement, Derain’s works were similarly characterized by their vibrant palette and unusual color associations. His paintings—such as London Bridge and Charing Cross Bridge—use bold, unmodulated colors to capture the essence of the scene.

Like Matisse, Derain’s groundbreaking Fauvist works were exhibited at the 1905 Salon d’Automne. Derain’s close association with Matisse is well-documented—especially their time together in Collioure. He also collaborated with Vlaminck early in his career—sharing a studio in Chatou.

Raoul Dufy (1877-1953)

Though Dufy’s association with Fauvism was brief, his early works like The Wheatfield resonate with the hallmarks of the movement. The Fauvist phase of this French painter is marked by a light and carefree approach to color—reminiscent of Matisse. Dufy and Braque attended the same art school in Le Havre and often painted together during their early careers.

Maurice de Vlaminck (1876-1958)

Often described as one of the “principal figures” in the Fauvist movement, Vlaminck was known for his bold use of color and strong brushwork. His style was influenced by the Impressionists and by Van Gogh. Vlaminck is known for landscapes that vibrantly capture the essence of each scene. Notable Fauvist works include his painting of the River Seine at Chatou from 1906.

Kees van Dongen (1877-1968)

A Dutch-born artist who spent most of his career in France, van Dongen was particularly recognized for his sensuous portraits of Parisian women. His use of exaggerated colors and bold outlines resonated with Fauvist principles. Van Dongen was part of the avant-garde circles in Paris—although direct collaborations in painting are less documented.

Charles Camoin (1879-1965)

A close friend of Matisse, Camoin’s works often depicted the landscapes of Southern France. His paintings of the natural world used a color palette that was characteristic of Fauvist artists. Camoin actually shared a studio with French artists Henri Matisse and Albert Marquet during his time at the École des Beaux-Arts. Notable Fauvist works include St. Tropez, Sailor with Mandolin from 1907.

Jean Puy (1876-1960)

Puy was a part of the Fauvist circle and exhibited with them at the d’Automne salon in 1905. His style was characterized by bright and pure colors applied in a direct and spontaneous manner. Notable Fauvist Works include Rue de l’Hermitage from 1909—which features the artist’s active brushwork.

Othon Friesz (1879-1949)

While Friesz’s association with Fauvism was relatively brief, his works from this period—marked by vivid colors and simplified forms—are indicative of the movement’s influence. After his brief Fauvist period, Friesz’s style evolved to reflect a more structured and orderly approach to composition. This shift was influenced by Cézanne’s work—with a stronger emphasis on geometric forms and a more restrained color palette.

Friesz later adopted elements of Cubism—integrating fractured planes and more abstracted forms into his work. However, he did not delve as deeply into Cubism as artists like Braque or Picasso. By the 1920s and 1930s, Friesz’s work became more classical—emphasizing balance and harmony—though his palette remained vibrant. This later phase is sometimes described as a return to order—echoing broader artistic trends in post-WWI France.

Albert Marquet (1875-1947)

A lifelong friend of Matisse, Marquet initially painted in a Fauvist style—characterized by its bright colors. However, he soon transitioned to a more subdued palette. Like Friesz, Marquet is particularly known for his post-Fauvist phase—which focused primarily on landscapes and cityscapes from North Africa all across Europe. Even as his palette became more restrained, Marquet maintained a certain simplicity and directness in his compositions.

Henri-Charles Manguin (1874-1949)

Often referred to as the “voluptuous painter” due to his preference for joyful and bright scenes, Manguin’s works from the early 20th century show the clear influence of Fauvism. After his Fauvist period, Manguin’s style retained the joyous use of color, but it evolved into a softer and more harmonious approach. The intensity of the Fauvist palette gave way to more nuanced and delicate hues.

The Influence of Fauvism on Later Modern Art Movements

Fauvism’s radical embrace of color, emotion, and non-representational form played a foundational role in shaping the trajectory of 20th-century art. Its legacy is evident in the myriad movements that valued emotion, abstraction, and innovation over strict adherence to representational norms.

While Cubism radically shifted focus to the abstraction and dissection of form, Fauvism’s departure from representational color paved the way for this experimentation. Artists like Georges Braque—who initially dabbled in Fauvism—were integral in the development of Cubism.

The Abstract Expressionists of the mid-20th century drew from the emotional intensity of Fauvism. Their emphasis on spontaneous, bold brushwork and the emotive power of color can be traced back to the Fauves. Color field painting—a subset of Abstract Expressionism—emphasized vast expanses of unbroken color. This resonated with the Fauvist passion for pure, unmodulated color.

Emerging in the late 20th century, Neo-Expressionism’s return to vivid coloration and emotive representation mirrors the Fauvist spirit—even if the context and intent differ.