10 Kinetic Artists Who Aren’t Alexander Calder

Summary

Kinetic sculpture, characterized by moving parts, extends beyond Alexander Calder’s iconic mobiles. This article introduces 10 inventive artists, from Naum Gabo to Jesús Rafael Soto, whose contributions have propelled the kinetic art movement forward with distinctive sculptures, constructions, and monumental installations.

Reflection Questions

- Reflect on the contributions of women artists to the development of kinetic art movements, such as Op art, Neo-Concrete art, and Kinetic sculpture. How have their unique perspectives and experiences shaped the evolution of these movements?

- Explore the themes and concepts explored by women kinetic artists in their work. How do they challenge traditional notions of sculpture, space, and movement through their artistic practice?

- Reflect on the role of collaboration and community among women artists working in the field of kinetic art. How have networks of support and mentorship contributed to their success and visibility?

Journal Prompt

Explore your own relationship with movement and motion in your artistic practice. Reflect on how you incorporate elements of kinetics or dynamic energy into your work, whether through sculpture, installation, performance, or other mediums. How does movement contribute to the meaning and impact of your artwork? Journal about this evolution.

Defined by artworks with parts that either move on their own or are movable, kinetic sculpture has continually expanded the boundaries of visual art and space. Alexander Calder—a pioneer of kinetic sculpture—cemented his legacy with delicate mobiles that drift in ambient air currents. Yet—beyond the well-known mobiles of Alexander Calder—lies a panorama of inventive artists who have propelled the medium forward with their own distinctive contributions. From Naum Gabo to Jesús Rafael Soto, these artists have created kinetic sculptures, constructions, and monumental installations that awe visitors all around the world. Read on to learn more about the kinetic art movement and its contributors.

Beginnings: The Kinetic Art Movement

The roots of kinetic art can be traced back to the early 20th century—intertwining with the development of the avant-garde. It was not until the 1950s and 1960s—however—that kinetic art emerged as a defined movement. This period saw artists exploring ways to incorporate time, motion, and the perception of the viewer into their works, which resulted in the genre gaining a distinct identity.

One of the earliest proponents of what would become known as kinetic art was Marcel Duchamp. His 1913 work “Bicycle Wheel”—which was simply a wheel mounted onto a stool, is often cited as the first kinetic sculpture—albeit its motion was not continual but could be set in motion by the viewer. Naum Gabo’s “Kinetic Construction” (also known as “Standing Wave”)—created in 1919-1920—is another early example where he used motorized parts to create the illusion of movement and is often considered a pioneering work of kinetic art.

In the 1930s, Alexander Calder—known for his mobiles—became one of the central figures of kinetic art. His work was crucial for the movement, as he crafted sculptures with balanced and weighted elements that moved in response to wind or touch—thus giving sculpture an entirely new dimension: time. Of course, plenty of earlier art (music, etc.) had a time-based element. Calder’s breakthrough was making sculpture’s time dimension obvious through unpowered movement.

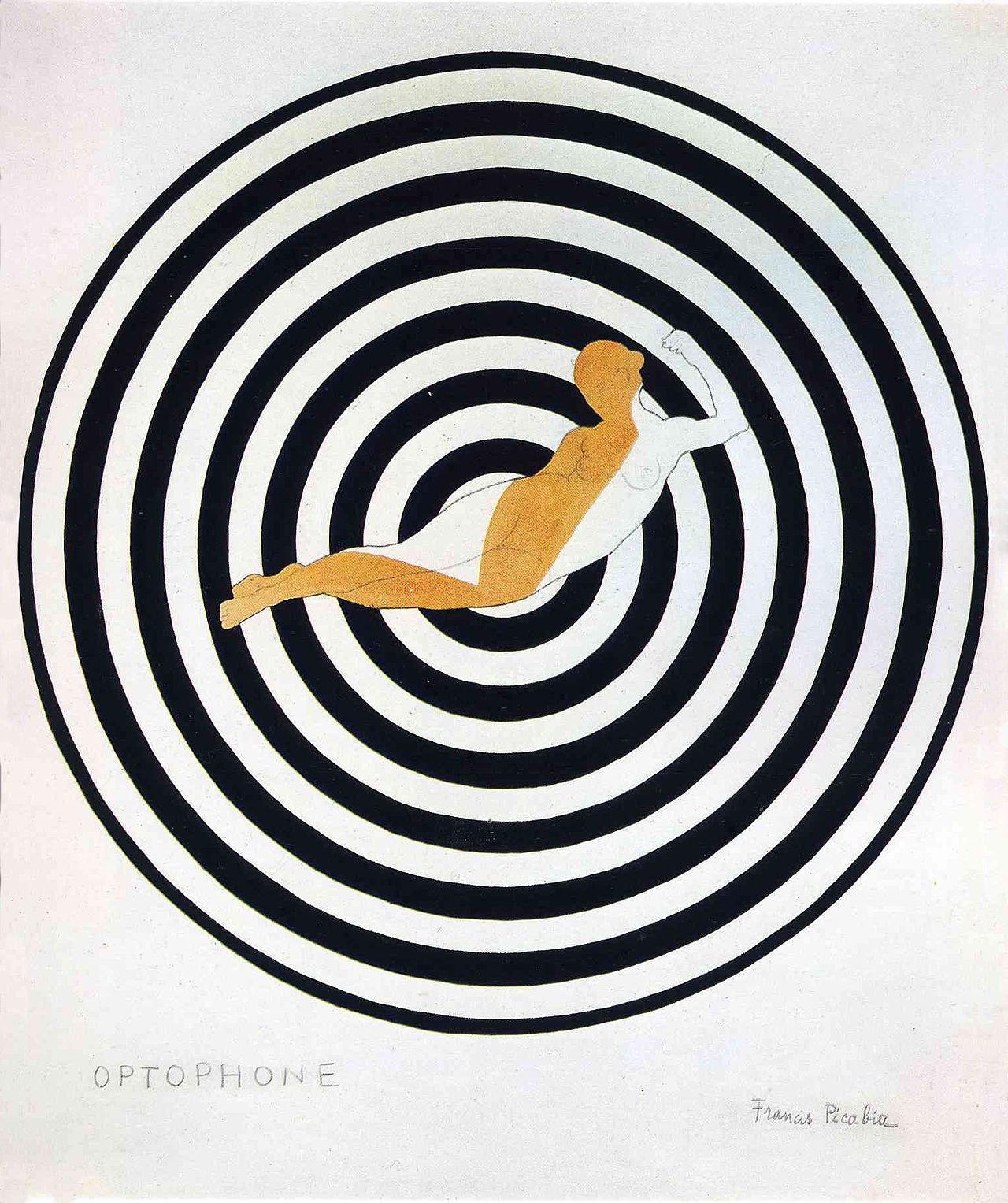

Overlapping with the Op Art Movement

Kinetic and op art significantly overlapped in the 1960s. While kinetic art will typically incorporate multidimensional movement within a single piece, Op Art focuses on incorporating movement via optical illusions on static surfaces.

Victor Vasarely—often regarded as the father of Optical Art—created works that seemed to vibrate and pulsate—manipulating the retina of the eye and the mind of the viewer. Bridget Riley is another key Op Artist whose works gave an impression of movement through patterns and contrasts. Although distinct in their focus, both movements shared an interest in perception and the viewer’s experience—blurring the lines between the artwork and its audience.

The term “kinetic art” was popularized by the landmark exhibition “Le Mouvement” at Galerie Denise René in Paris in 1955. This exhibition showcased artists who were interested in both the actual and apparent movement—including pieces by modern art icons Yaacov Agam, Pol Bury, Alexander Calder, Marcel Duchamp, Jean Tinguely, and Victor Vasarely—solidifying the group’s aesthetic aims and shared philosophies.

Fuel your creative fire & be a part of a supportive community that values how you love to live.

subscribe to our newsletter

Jean Tinguely is another foundational artist of the kinetic art movement—known for his “metamechanics.” These sculptural machines appeared to fulfill some sort of function but were actually absurd and often self-destructing. His “Homage to New York”—a machine that self-destructed in the Museum of Modern Art’s garden in 1960—is a prime example.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, kinetic art continued to evolve with the use of new materials and technologies. The introduction of electric motors, sensors, and later, digital and computer technology, allowed for more sophisticated and interactive artworks. Today, kinetic art encompasses a wide range of media and technologies.

It’s important to note that while this artistic movement had key figures and landmark exhibitions that helped to define it, it was a broad and international movement with numerous artists contributing independently to its growth and development. Many of these artists shared the goal of creating art that broke free from traditional static forms to engage directly with time, space, and the sensory experiences of the viewer.

Kinetic Art’s Relationship with the Viewer

Kinetic artworks are often engineered to move naturally with wind or light or are powered by motors—inviting not just passive observation but interactive experiences. The relationship between kinetic art and the viewer is dynamic and multifaceted.

As the artwork moves, the viewer’s perception is engaged in a temporal experience. The piece is never perceived the same way twice—ensuring a unique encounter with each viewing. This interactivity with the observer is key to developing kinetic movement, as this motion is often influenced by or responsive to the viewer’s presence or actions—which blurs the traditional boundaries between artwork and audience.

Technological advancements have had a profound influence on the evolution of kinetic art. The initial phases of the movement utilized simple mechanics, but as technology progressed, so did the complexity and capabilities of kinetic art.

are you a fine artist or photographer?

By introducing electronic components, digital controls, and computer programming, artists have expanded the scope of how movement can be incorporated into contemporary art. Artists have harnessed these new technologies to create works that respond to environmental factors—such as sound and light, or that include sophisticated programming to produce sequenced or randomized motion—thereby offering a commentary on the integration of technology in modern life.

The Kinetic Movement indirectly challenged modern society. As we continue to advance technologically, kinetic art remains at the forefront of exploring and integrating new mediums—pushing the boundaries of how art is defined, experienced, and understood.

Alexander Calder’s Kinetic Art and Influence on the Movement

Alexander Calder—an American sculptor born in 1898—profoundly revolutionized the domain of sculpture by introducing the element of motion into his works. The progeny of artists—his father was a sculptor and his mother a painter—Calder was predisposed to a life in the arts, yet his approach was anything but traditional. Trained as a mechanical engineer, Calder applied his understanding of materials and mechanics to art—giving birth to a new sculptural form: the mobile.

Calder’s mobiles—a term coined by Marcel Duchamp—were a ground-breaking departure from established sculptural norms. They were not static. Instead, they embraced the movement—making air currents their collaborator. These delicately balanced structures move in response to the slightest air currents—engaging with the environment in a perpetual, silent performance.

With this, Calder introduced the fourth dimension—time—into sculpture. His work was revolutionary in its refusal to remain constant and in its dialogue with the space around it. By integrating motion, Calder’s sculptures possessed an inherent unpredictability and an organic quality that mirrored the natural world.

Calder’s Enduring Influence on Later Kinetic and Op Artists

The impact of Calder’s kinetic sculptures rippled through the art world and beyond—inspiring countless artists. His influence can be seen in the works of contemporary artists like Takis—who harnesses electromagnetic energy to create movement—and Tim Prentice—who focuses on the play of light and shadow through his mobiles. Kinetic artists such as George Rickey have expanded on Calder’s principles—constructing large-scale outdoor works that respond to wind, while others—like Rebecca Horn—have infused kinetic principles into performance art.

Calder’s legacy is not confined to those who create mobiles or kinetic sculptures. His ethos of infusing art with dynamism and spontaneity profoundly impacted modern society and echoes in the practices of artists across various mediums. His inventive spirit continues to spark the imagination of modern and contemporary artists who see in his work an enduring challenge to explore and expand the boundaries of what art can be.

His mobiles—standing as precursors to interactive art—laid the groundwork for other artists to consider the viewer’s experience as an integral part of the artwork itself. Through his moving sculpture kinetic construction, Calder was able to transform an element of everyday life into a magical art object.

10 Kinetic Artists Who Aren’t Alexander Calder

These artists represent a diverse array of styles and approaches within the kinetic art movement, from those who create subtle movements to those who integrate technology for more complex motion. Each has contributed to the field in significant ways—pushing the boundaries of what is possible in art that incorporates motion.

Naum Gabo

Naum Gabo—born Naum Neemia Pevsner in Bryansk, Russia in 1890—was a seminal figure in the establishment of constructivism—an artistic and architectural philosophy that emerged in Russia in the early 20th century. Gabo’s early life was steeped in the intellectual vigor of pre-revolutionary Russia, and this formative environment—coupled with his studies in engineering and natural science in Munich—profoundly influenced his artistic trajectory.

Rejecting the traditional static and mass-filled sculpture, Gabo pioneered a vision of sculpture as a construct of space and time—emphasizing void over volume and dynamic form over solid mass. His visionary ideas were crystallized in the 1920 “Realistic Manifesto”—which he co-authored with his brother Antoine Pevsner—a document that underscored the use of real materials to create real space and rhythm in time.

Notable Works

Gabo’s oeuvre is characterized by its innovative use of industrial materials such as perspex, plastic, and metallic filaments—which allowed him to explore the interplay of form, space, and light. One of his most celebrated works—the “Kinetic Construction (Standing Wave)” produced in 1919-1920—was a pioneering endeavor in kinetic sculpture. It utilized a motor to generate rhythmic movement.

Another notable work—”Construction in Space: Two Cones”—embodies Gabo’s mastery of spatial construction, where the transparent surfaces and intersecting planes create a complex interplay of depth and light—challenging the viewer’s perception of space. Through his meticulous constructions, Gabo did not merely aim to reflect the modern experience but sought to sculpt time itself—engaging viewers in a dialogue with the fourth dimension.

His works stand as testament to the power of artistic innovation and remain influential in the discourse of sculpture and kinetic art.

Jean Tinguely

Jean Tinguely—born in Fribourg, Switzerland, in 1925—was a prominent artist known for his kinetic art sculptures, a form of art that incorporates movement perceivable by the viewer. Tinguely’s craft was deeply rooted in the Dada tradition—valuing nonsense, whimsy, and the critique of overwrought intellectualism in art.

His beginnings in the European post-war art scene led him to reject the static conventions of sculpture—instead embracing motion and mechanical sound as artistic elements. Tinguely is best known for his “Méta-matics” series, which were sculptural machines designed to create abstract drawings—highlighting the absurdity of the mechanized process over the finished product.

Perhaps his most infamous work—”Homage to New York” (1960)—was a self-destroying machine that spectacularly self-dismantled in the garden of the Museum of Modern Art, New York—symbolizing the transient nature of the modern world. Through such works, Tinguely challenged the boundaries of art—making him a critical figure in kinetic art and a provocateur in discussions about the intersection of art, technology, and obsolescence.

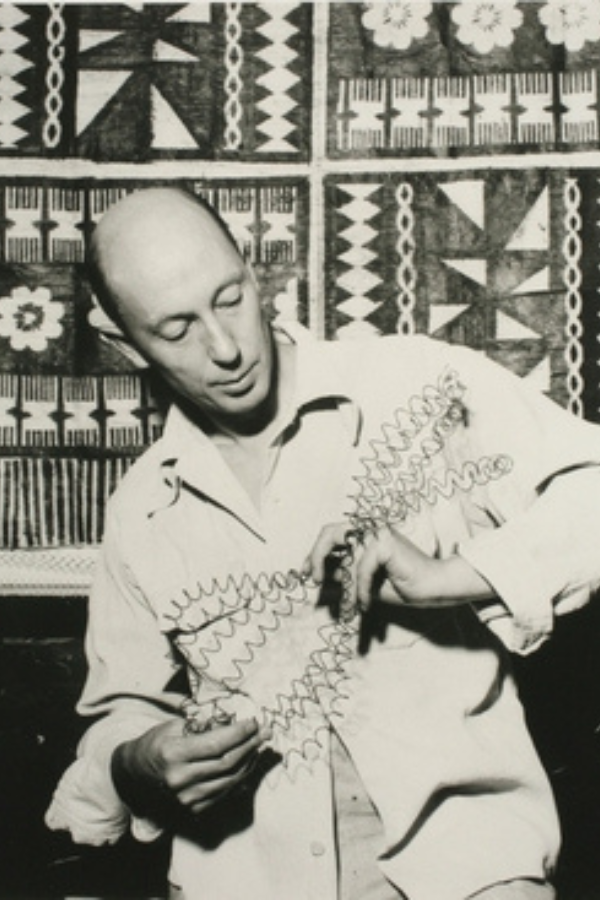

Len Lye

Len Lye—born Leonard Charles Huia Lye in 1901 in Christchurch, New Zealand—was an artist renowned for his pioneering work in kinetic sculpture and experimental film. His exploration into the dynamics of motion led to his creation of ‘Tangible Motion Sculpture’—a term he coined to describe his unique approach to the medium.

Lye’s early forays into art were influenced by his interest in indigenous art from the South Pacific—which later expanded to include elements of energy and movement. His notable kinetic sculptures include “Wind Wand” and “Flip and Two Twisters”—which are lauded for their innovative use of materials like metal and plastic to translate rhythmic movement into visual form.

Lye’s work extended beyond sculpture. His experimental films—such as “A Colour Box” (1935) and “Free Radicals” (1958)—were equally groundbreaking, employing techniques like direct animation, where he painted and scratched images directly onto celluloid film. Lye’s contributions to art embody a curiosity and a fascination with the potential for movement and light to express the vivacity of life—securing his place as a significant figure in kinetic art.

Rebecca Horn

Rebecca Horn—born in 1944 in Michelstadt, Germany—is an eminent contemporary artist whose multidisciplinary work encompasses performance art, installations, and kinetic sculpture. Her foray into the art world was marked by a period of illness early in her career—which profoundly influenced her subsequent creations that often feature themes of confinement, liberation, and human vulnerability.

Horn is renowned for her body-extension pieces—such as “Finger Gloves” and “Pencil Mask”—which extend the body in space and explore the interaction between human physiology and the external world. Among her celebrated kinetic sculptures is “Concert for Anarchy” (1990)—where an upside-down grand piano hangs from the ceiling. Its parts periodically burst outward—challenging traditional perceptions of form and function.

Horn’s craft is characterized by poetic mechanics—combining the mechanical and the organic to create works that are not only visually striking but also deeply contemplative—addressing the complexities of human existence and the inexorable passage of time. Her work holds a critical place in the discourse on body and machine in contemporary art.

Arthur Ganson

Arthur Ganson is a kinetic sculptor who merges the mechanical with the museological to craft machines imbued with a playful, almost meditative motion. Born in 1955, Ganson has developed a distinct niche within the kinetic art landscape since the late 1970s.

Trained as an artist at the University of New Hampshire, he has eschewed the grand scale typical of some kinetic sculptures—opting instead for an intimate approach that invites close observation. His works—characterized by their delicate intricacy and philosophical humor—often involve complex gear mechanisms that produce fluid, continuous movement.

Notable among Ganson’s oeuvre is “Machine with Concrete”—a statement on the paradox of motion and stasis where a set of seemingly perpetual gears turns so slowly that its embedded block of concrete never actually moves. Ganson’s sculptures—including “Cory’s Yellow Chair”—which spontaneously assembles and disassembles itself, achieve a profound commentary on the interplay between the engineered and the organic—ultimately reflecting on the nature of existence through the lens of the inanimate.

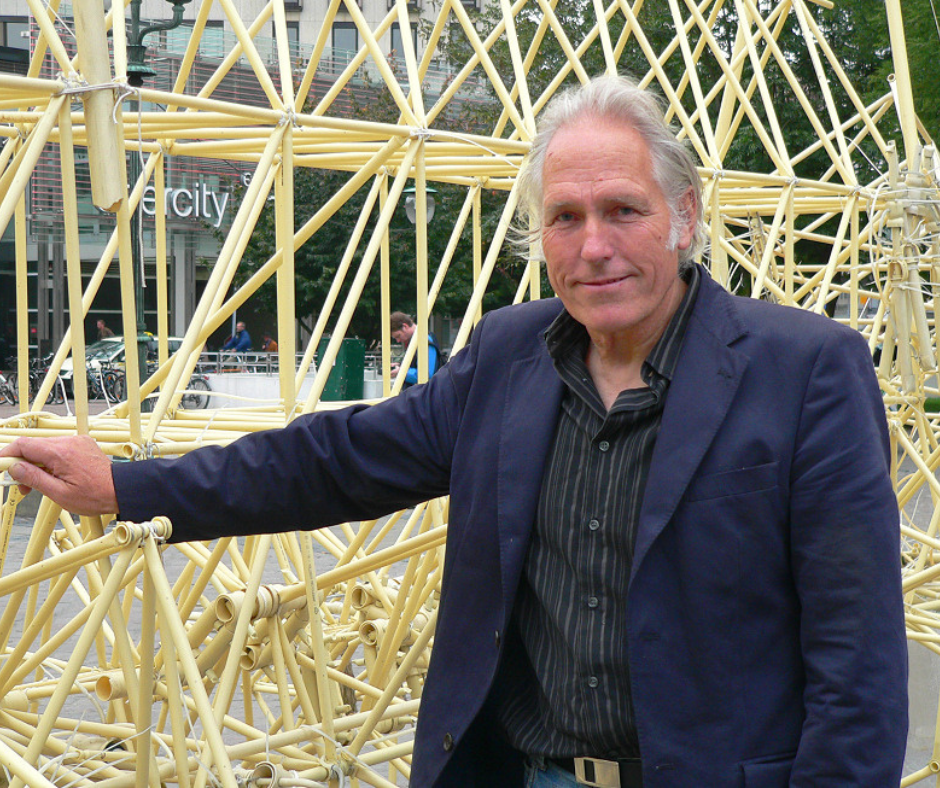

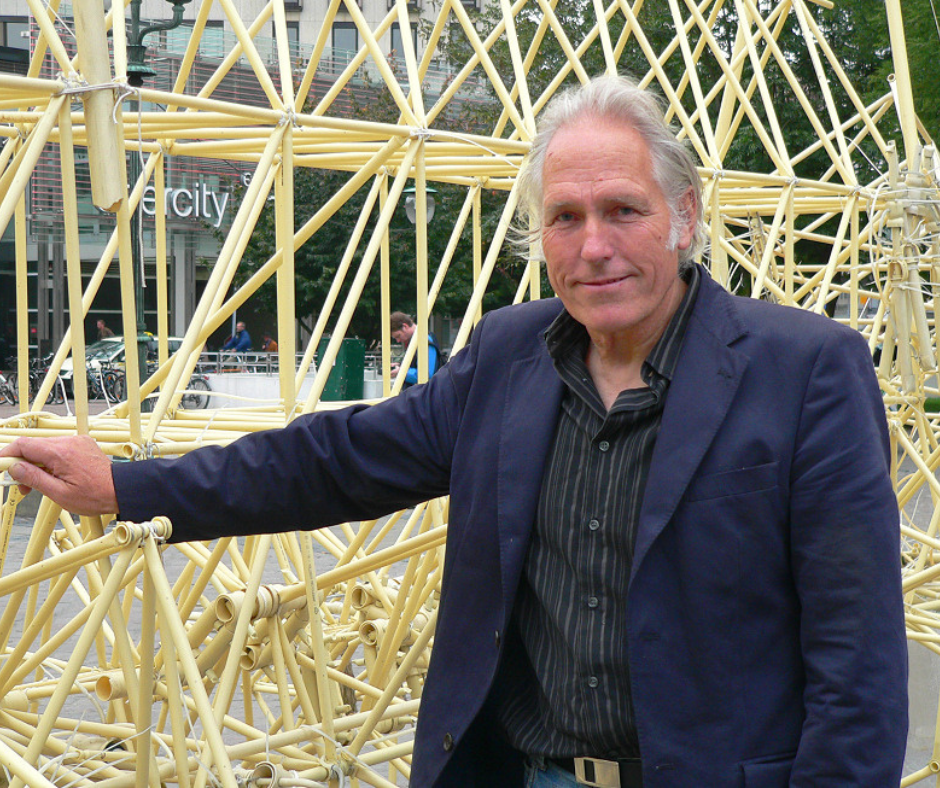

Theo Jansen

Theo Jansen—born in 1948 in the Netherlands—is a kinetic sculptor who transcends the traditional boundaries of art, engineering, and biology. Educated in physics at Delft University of Technology, Jansen is best known for his Strandbeests—large, autonomous structures that appear as complex, animated creatures roaming the shorelines.

Constructed from lightweight PVC tubing and fabric airfoils, these self-propelling beasts harness wind power and embody the synthesis of industrial design and evolutionary theory. Jansen’s evolutionary design process includes ‘survival of the fittest’ experiments where mechanisms are refined over successive generations to better adapt to their sandy environments.

Among his notable creations, “Animaris Rhinoceros Transport” is a massive wind-powered structure that weighs over 300 kilograms—demonstrating Jansen’s dexterity in scaling his unique brand of biomechanical art. His work not only captivates the imagination but also ignites dialogue on sustainability and the future of robotic automation in harmony with natural landscapes.

George Rickey

George Rickey—an American kinetic sculptor—was a seminal figure in the kinetic art movement, known for his silent, delicately balanced works that respond to the slightest air currents. Born in 1907, Rickey’s journey into kinetic sculpture was influenced by his experiences in engineering during World War II.

His academic pursuits at Oxford and Paris, coupled with a background in painting, gradually led him to sculpture and eventually to kinetic art in the late 1940s. Rickey’s precision-engineered, geometric forms—often crafted in stainless steel—exemplify a rigorous exploration of materiality and motion.

His sculptures—such as “Two Lines Temporal” and “Four Squares in Geviert”—embody a minimalist aesthetic, yet engage complex physical principles to create a visual interplay of balance, weight, and air resistance. Rickey’s work stand out for their capacity to integrate the mechanical with the environmental—producing a choreography of elements that is both exact and unpredictable.

Carlos Cruz-Diez

Carlos Cruz-Diez—a leading Venezuelan kinetic and op artist—was a major proponent of color theory in the 20th century. Born in 1923, Cruz-Diez’s artistic journey began in Caracas—where he initially worked in graphic design and illustration.

His transition to kinetic art was marked by his interest in color as an autonomous reality—evolving without narrative or support. His major contributions to the field are characterized by the interaction of color and light, and the concept of “Chromointerference”—where he manipulates color behavior to create an impression of movement.

Cruz-Diez’s prominent works—such as “Physichromie” and “Chromosaturation”—engage viewers in an active dialogue with the artwork, as their perception of color changes with their position and movement. His artistic endeavor is not just an aesthetic experience but an ongoing research into the visual phenomena—examining how color and light can transform space and influence human perception.

Jesús Rafael Soto

From Ciudad Bolívar, Venezuela, Jesús Rafael Soto became a defining figure in the kinetic art and op art movements. His educational foundation in art began at the Escuela de Artes Plásticas y Artes Aplicadas in Caracas—which steered him towards his fascination with the dynamics of visual perception.

Soto’s practice revolved around the integration of space and viewer participation, exemplified in his signature “Penetrables,” interactive sculptures consisting of hanging tubes or rods that viewers can walk through—thereby becoming part of the artwork. His utilization of industrial materials and the interplay of lines and geometric forms create visual experiences where the perception of motion is activated by the spectator’s movement.

Notable works like “Vibración” and “Double Transparence” highlight his commitment to exploring the instability and relativity of the visual experience—challenging the traditional boundaries between artwork and observer.

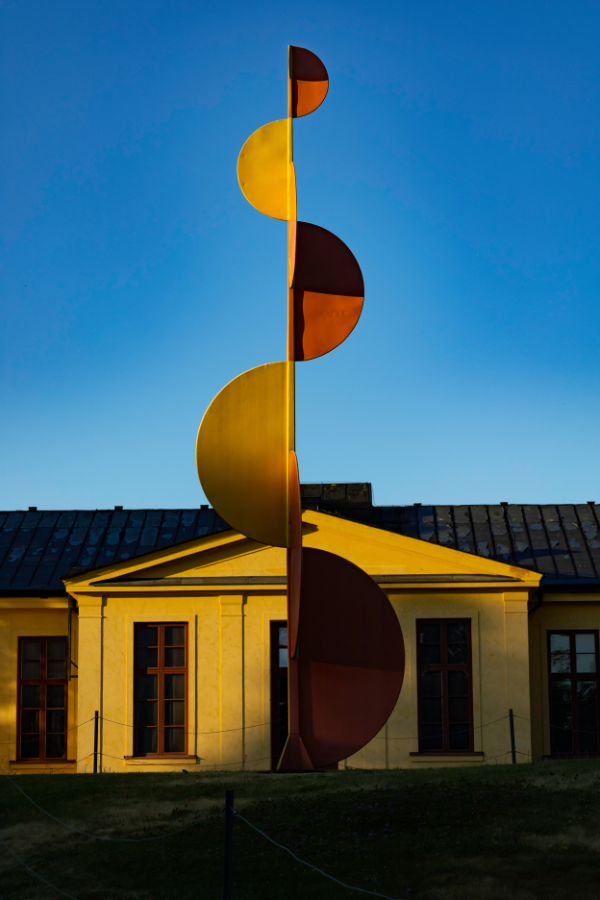

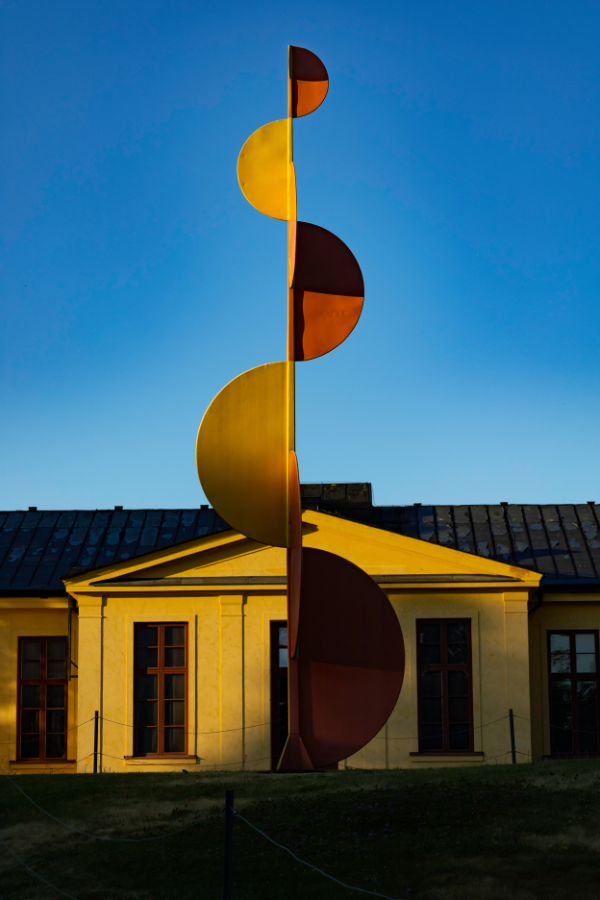

Nikolaus Koliusis

Nikolaus Koliusis—a German artist of Greek descent—is known for his work that straddles the realms of kinetic art and architectural intervention. Born in 1953, Koliusis was educated in Fine Arts at the Stuttgart State Academy of Art and Design—laying a foundation that propelled his exploration of space, light, and movement.

His oeuvre is distinguished by the use of translucent and reflective materials—such as colored films and mirrors—that interact with the built environment and its inhabitants. One of his notable series—”Sky Over Nine Columns”—showcases his affinity for creating spatial experiences that are both immersive and transient—altering the viewer’s perception of their surroundings through subtle yet impactful manipulations of light and color.

Koliusis’s work not only redefines the physical spaces it inhabits but also invites contemplation on the ephemeral nature of perception and the fluid boundaries of art and architecture.

Final Thoughts About the Future of Kinetic Art

Kinetic and op art continue to intrigue and inspire both the art community and the public at large with their dynamic interplays of movement and form. The field extends far beyond the pioneering works of Alexander Calder—encompassing a diverse array of artists each contributing a unique voice and vision to the genre.

Readers are encouraged to explore the rich tapestry of kinetic art—discovering the less heralded but equally influential artists who bring motion into their creations. As we engage with and create art, we are reminded of its unceasing evolution and the ways in which it challenges our perceptions. Kinetic art in particular infuses the spaces it inhabits with the palpable energy of movement—an art form forever in flux, mirroring the perpetual motion of life itself.

Design Dash

Join us in designing a life you love.

-

All About Our 7-Day Focus & Flex Challenge

Sign up before August 14th to join us for the Focus & Flex Challenge!

-

Unique Baby Names Inspired by Incredible Women from History

Inspired by historic queens, warriors, artists, and scientists, one of these unusual baby names might be right for your daughter!

-

Finding a New 9 to 5: How to Put Freelance Work on a Resume

From listing relevant skills to explaining your employment gap, here’s how to put freelance jobs on your resume.

-

What is Generation-Skipping, and How Might it Affect Sandwich Generation Parents?

The emotional pain and financial strain of generation skipping can be devastating for Sandwich Generation parents.

-

Four Material Libraries Dedicated to Sustainability, Preservation, and Education

From sustainable building materials (MaterialDriven) to rare pigments (Harvard), each materials library serves a specific purpose.

-

Do You Actually Need a Beauty Fridge for Your Skincare Products? (Yes and No.)

Let’s take a look at what dermatologists and formulators have to say about whether your makeup and skincare belong in a beauty fridge.