All About Dada (c. 1916 – 1920s): Its Inspirations, Artists, and Influence on Later Movements

Summary

The Dada movement, born out of the chaos of World War I in the 1910s, was a revolutionary art movement that rejected traditional aesthetics and cultural norms. Emphasizing absurdity, anti-art sentiments, and a break from conventional artistic practices, Dadaists aimed to undermine the societal values that they believed led to the war. Through a mix of visual arts, literature, and performance, Dada challenged the foundations of art, influencing future avant-garde movements and reshaping modern and contemporary art. This article explores Dada’s origins, key figures, and its lasting impact on art and society, highlighting its role as a critical precursor to major artistic innovations.

Reflection Questions

- Dadaism celebrated the absurd and the irrational, often through the lens of anti-war and anti-establishment sentiments. How might these themes resonate with contemporary feminist movements that challenge societal norms and structures?

- Dada artists utilized collage, performance, and other non-traditional mediums that broke away from the conventions of fine art. How can these practices be seen as a form of liberation or expression for women artists, both historically and in contemporary contexts?

- How did the Dada movement challenge or reinforce the gender norms of its time? Consider the roles and representations of women within the Dada movement and the broader societal context of the early 20th century.

Journal Prompt

The Dada movement embraced the absurd and the irrational as a response to the chaos and destruction of World War I. Reflect on a moment in your life or a situation in the world today that seems absurd or irrational. How do you respond to this absurdity? Do you find humor, frustration, or perhaps a sense of liberation in recognizing the absurd aspects of life?

The Dada movement, emerging amid the tumultuous backdrop of World War I, circa 1916, and extending into the 1920s, was a defiant rebuttal to the traditional values and aesthetic norms of its time. Characterized by its irreverent humor, a penchant for the absurd, and a radical departure from conventional art forms, Dadaism challenged the very foundations of art-making and its role in society. In this article, we will delve into the origins and historical context of Dada, examining the influences that shaped this avant-garde movement and its key proponents. We will also underscore Dada’s profound and enduring impact on subsequent art movements, celebrating its pivotal role in the evolution of modern and contemporary art.

Origins and Historical Context of the Dada Art Movement

The birth of this modern art movement was deeply intertwined with the socio-political climate of World War I, a period marked by unprecedented destruction and disillusionment with traditional societal structures. The war, with its massive human and cultural costs, catalyzed a profound sense of skepticism and cynicism among artists and intellectuals.

This widespread disenchantment was particularly pronounced in Europe, where the ravages of war directly challenged longstanding beliefs about progress, rationality, and the role of culture in society. In response to this, Dada emerged as an artistic and cultural movement that vehemently rejected the rationalism and aesthetic norms that many believed had led to the war.

The Founding of Dada in Zurich and Its Philosophical Underpinnings

Dada was officially founded in Zurich, Switzerland, a neutral territory during the war, in 1916. The city became a refuge for a diverse group of artists, writers, and intellectuals from across Europe who were fleeing the conflict. In Zurich, these individuals found an environment where they could freely express their disillusionment.

The Cabaret Voltaire, founded by Hugo Ball, became the epicenter of Dada activity, where artists like Tristan Tzara, Jean Arp, and Marcel Janco congregated. The philosophical underpinnings of Dada were rooted in a radical rejection of traditional values and a quest for freedom in artistic expression. It embraced chaos, absurdity, and spontaneity as a means to counteract the perceived rationalism and bourgeois values that they held responsible for the war.

Discussion of Dada’s Initial Purpose as an Anti-War, Anti-Bourgeois Cultural Movement

Initially, Dada positioned itself as an anti-war, anti-bourgeois cultural movement. Its proponents used their art as a form of protest against the nationalist and materialist ideologies that dominated European politics at the time. Dadaists expressed their disdain for the war and the societal structures supporting it through their art, which often took the form of outrageous performances, provocative writings, and the creation of anti-art pieces.

These works were intentionally irrational and nonsensical, reflecting the Dadaists’ belief that the absurdity of their art was a fitting response to the absurdity of the world situation. By challenging the conventional notions of art and culture, Dadaists sought to undermine the status quo and create a new paradigm that eschewed the norms that had led to such catastrophic conflict.

Key Characteristics of Dada

Dada art is distinguished by several defining characteristics, the most prominent of which is its embrace of absurdity and irony. This was a deliberate response to the senseless destruction of World War I, which Dadaists viewed as the product of a rational yet deeply flawed European culture.

By incorporating absurd elements into their work, Dada artists sought to mock the seriousness and rationality of established cultural and artistic norms. This approach manifested in various forms, from nonsensical poetry to bizarre collages, all aimed at defying logical interpretation and provoking thought and amusement.

Fuel your creative fire & be a part of a supportive community that values how you love to live.

subscribe to our newsletter

Dada’s Emphasis on Spontaneity and Rejection of Traditional Aesthetic Values

Spontaneity was another cornerstone of the Dada movement, reflecting its opposition to the calculated and traditional methods of art creation. Dadaists believed that spontaneity could counteract the constraints imposed by traditional artistic standards and societal expectations.

This emphasis led to the production of works that were often unplanned and improvisational in nature. It was not uncommon for Dada artists to engage in activities that embraced randomness and chance, as they felt this approach was more authentic and reflective of the chaotic reality of their times.

Analysis of the Use of Readymades and Performance in Dada

A significant aspect of this artistic and literary movement was its innovative use of readymades and performance art. Readymades, a concept popularized by Marcel Duchamp, involved the designation of everyday objects as art, challenging the notion of what constitutes artistic creation. This radical idea questioned the traditional skills and processes associated with art-making, pushing the boundaries of what was considered art. Performance art, too, played a crucial role in Dada.

Performances in Dada were often theatrical, involving absurd and shocking elements designed to disrupt societal norms and provoke reactions from the audience. These performances could include anything from nonsensical lectures to bizarre costume displays, all intended to defy conventional artistic expression and engage directly with the public in provocative ways. Together, the use of readymades and performance art underscored Dada’s commitment to redefining art and its role in society.

Influential Artists and Works

Among the key figures in the Dada movement, Tristan Tzara stands out as one of its most vocal and influential proponents. As a poet and performance artist, Tzara’s works exemplified the Dada spirit of spontaneity and absurdity. His methods, particularly the technique of creating poetry by randomly assembling cut-up words, were revolutionary. Tzara’s writings and performances were instrumental in defining the anarchic and anti-establishment ethos of Dada.

Marcel Duchamp

French artist Marcel Duchamp is renowned for profoundly altering the trajectory of modern art. His concept of the readymade, epitomized by his 1917 work “Fountain,” a porcelain urinal presented as art, challenged conventional notions of art-making and authorship.

Duchamp’s approach, characterized by intellectualism and a playful engagement with art’s boundaries, made him a central figure in Dada. His influence extended well beyond Dada, shaping Surrealism and Conceptual Art, and his legacy continues to resonate in contemporary discussions about the nature and function of art. It is his work, alongside other artists, that propelled Dada forward and established it as a significant movement in art history.

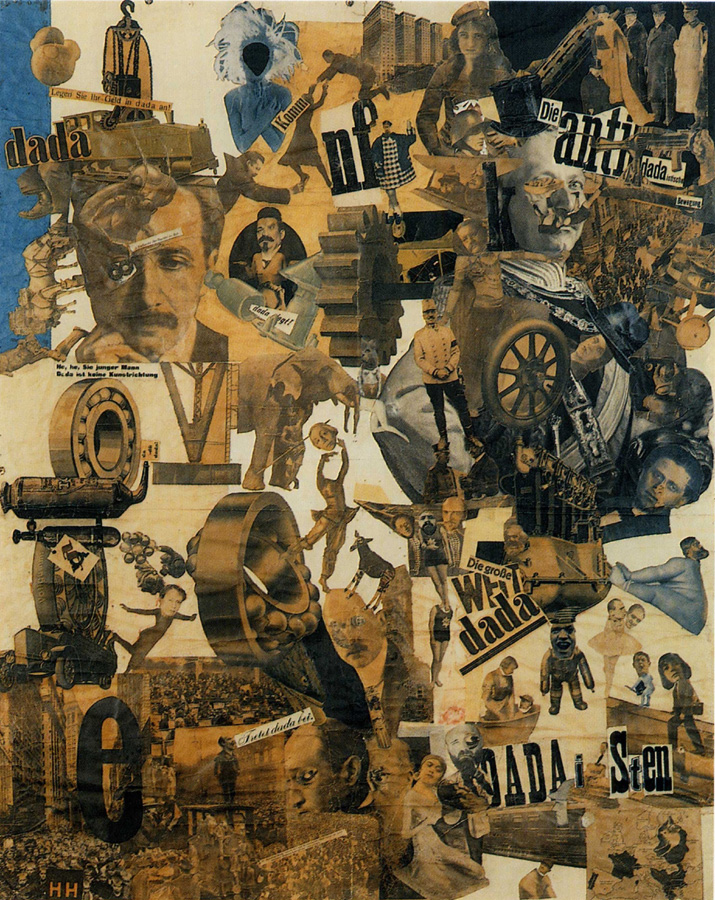

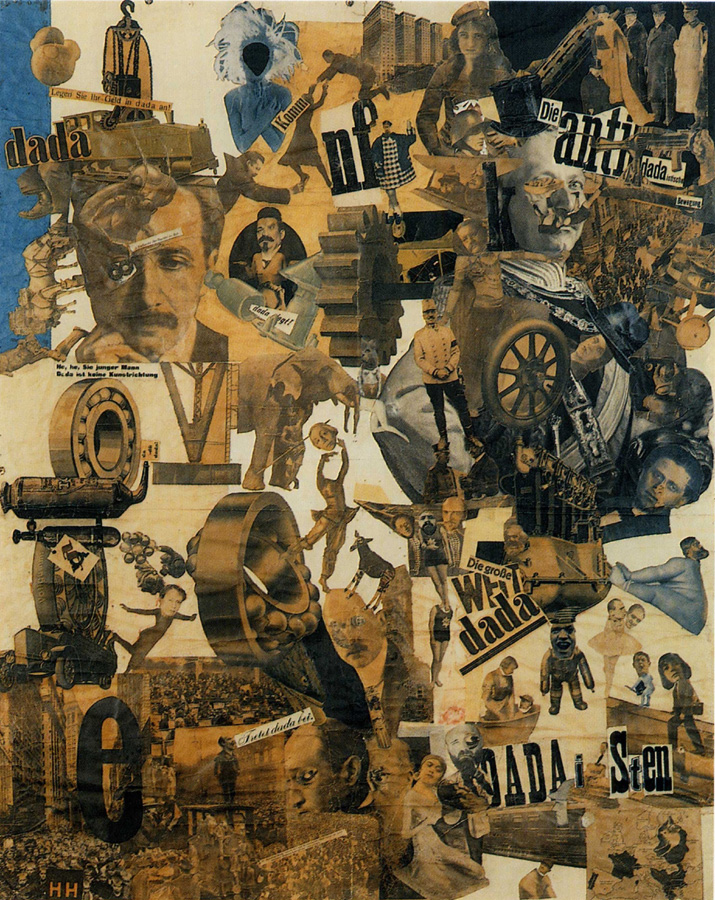

Hannah Höch

German artist Hannah Höch was a key figure in the Berlin Dada movement. Renowned for her pioneering work in photomontage, Höch’s compositions, often politically charged, critiqued the Weimar Republic and traditional gender roles.

Her art was characterized by its sharp wit and the juxtaposition of fragmented images, which challenged both artistic conventions and social norms, especially regarding women’s roles in society. Höch’s work, while underrecognized in her time, is now celebrated for its critical perspective and innovative techniques.

Jean (Hans) Arp

Jean (Hans) Arp was a German-French artist who contributed significantly to Dada’s development in Zurich and Paris. Known for his abstract sculptures and collages, Arp’s work was distinguished by organic forms and a rejection of geometric regularity.

His art, often seen as a bridge between Dada and Surrealism, emphasized natural processes and chance, reflecting Dada’s interest in spontaneity and the unconscious. Arp’s contributions were instrumental in expanding the scope of abstract art, influencing its evolution well into the mid-20th century.

George Grosz

George Grosz, a prominent member of the Berlin Dada group, was known for his caustic and satirical artwork. His drawings and paintings, which often depicted the social and political chaos of post-World War I Germany, were characterized by sharp lines and vivid, sometimes grotesque, imagery. Grosz’s work was a direct response to the tumultuous society of his time, and his biting critiques of corruption, capitalism, and militarism reflect the politically charged nature of Berlin Dada.

John Heartfield

John Heartfield, born Helmut Herzfeld, was a German Dada artist famous for his politically charged photomontages. A staunch anti-fascist, Heartfield used his art as a weapon against the Nazi regime, creating powerful compositions that critiqued Hitler and the rise of fascism in Germany. His work in visual propaganda and his innovative use of the photomontage technique had a lasting impact on the development of political art and graphic design.

André Breton

André Breton, initially associated with Dada in Paris, later became the founder and principal theorist of Surrealism. His work and writings during the Dada era were marked by a fascination with the irrational and the exploration of the unconscious, themes that he would carry into and further develop with Surrealism. Breton’s intellectual approach and leadership in both movements made him a pivotal figure in 20th-century art, influencing a wide array of artistic and literary practices.

Tristan Tzara

Tristan Tzara, a Romanian-born poet and performance artist, was one of the founding members of Dada in Zurich. Known for his anarchic and playful approach, Tzara’s art and writings epitomized the Dada spirit. His techniques, particularly the use of cut-up words to create poetry, embodied Dada’s embrace of chance and spontaneity. Tzara’s radical ideas and charismatic personality made him a central figure in Dada, and his influence extended to both the art and literature of the movement.

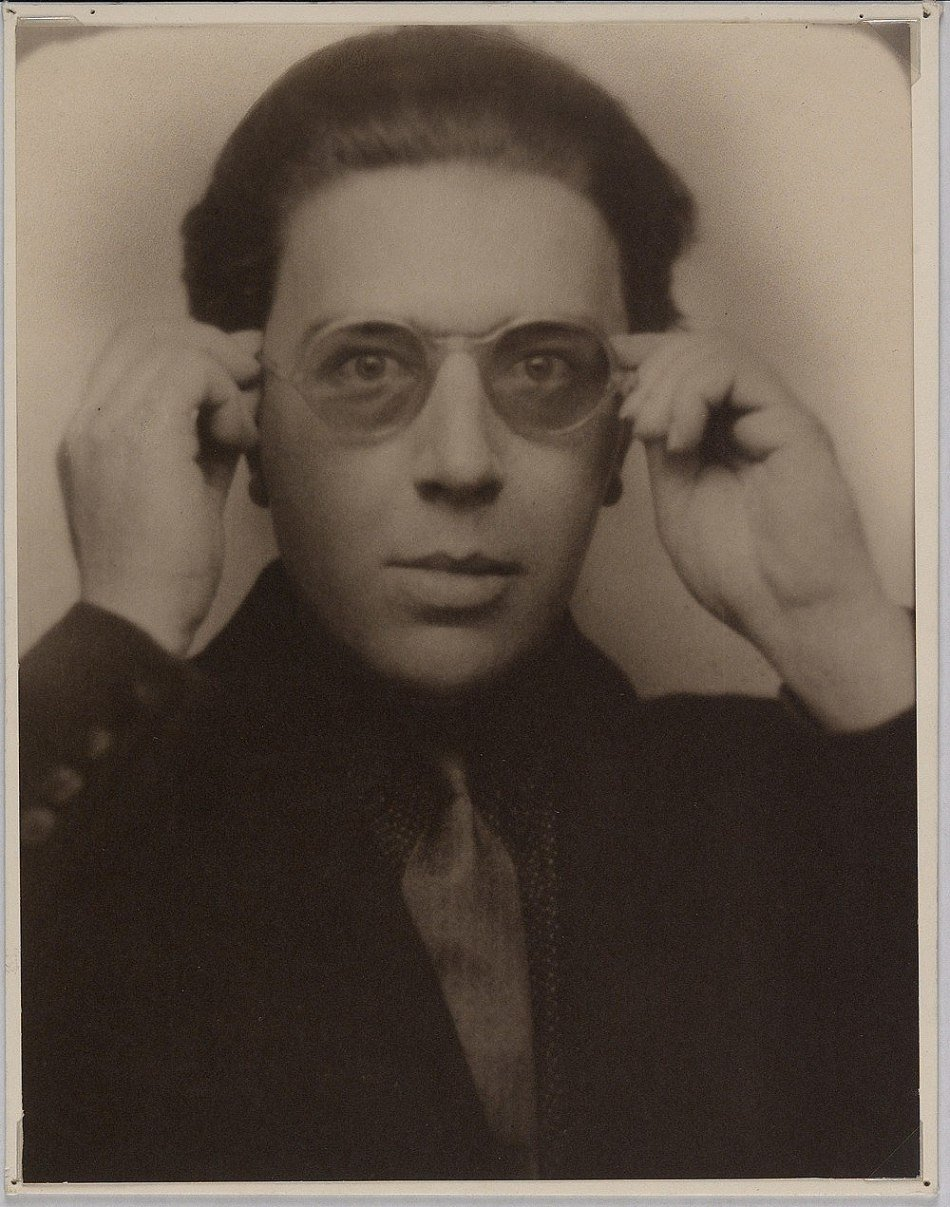

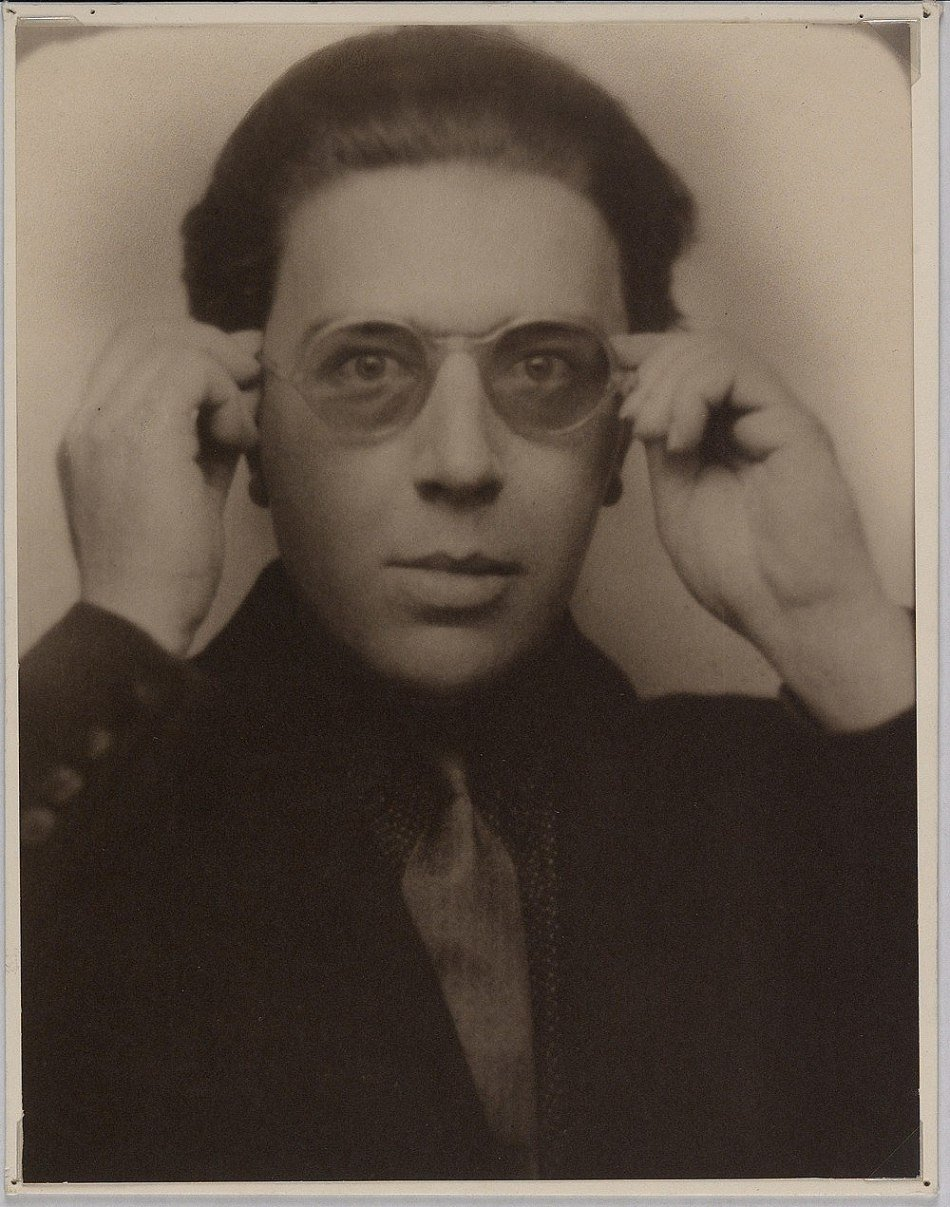

Francis Picabia

Francis Picabia was a French avant-garde artist who played a significant role in the development of several early 20th-century art movements, most notably Dada. Born in Paris, Picabia’s career was marked by constant innovation and a refusal to adhere to any single artistic style or convention.

Picabia began his artistic journey influenced by Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, but his style rapidly evolved. He dabbled in Cubism and was associated with the Puteaux Group, a collective of artists that included the Duchamp brothers. His involvement with Cubism, however, was brief and idiosyncratic, already showcasing his tendency to break with established artistic norms.

Picabia’s Contributions to Dadaism

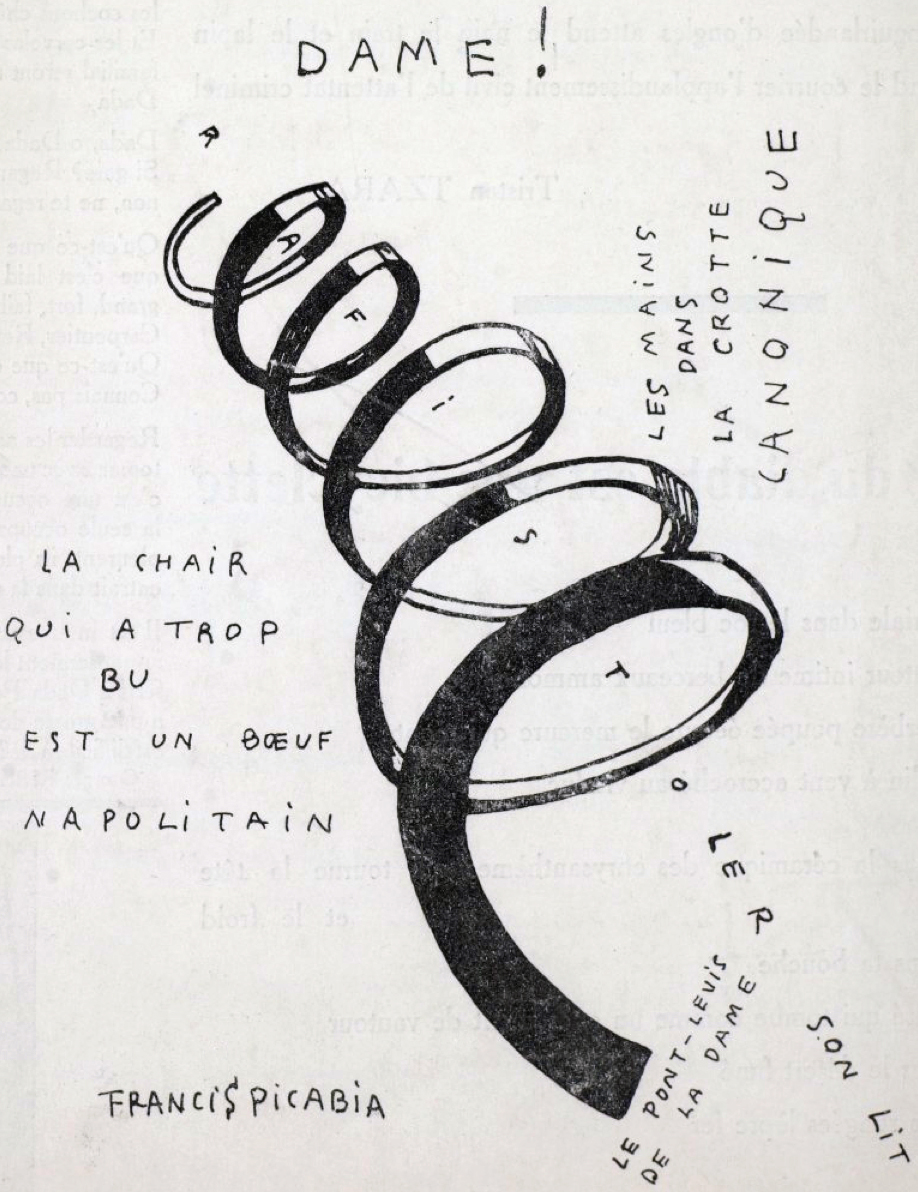

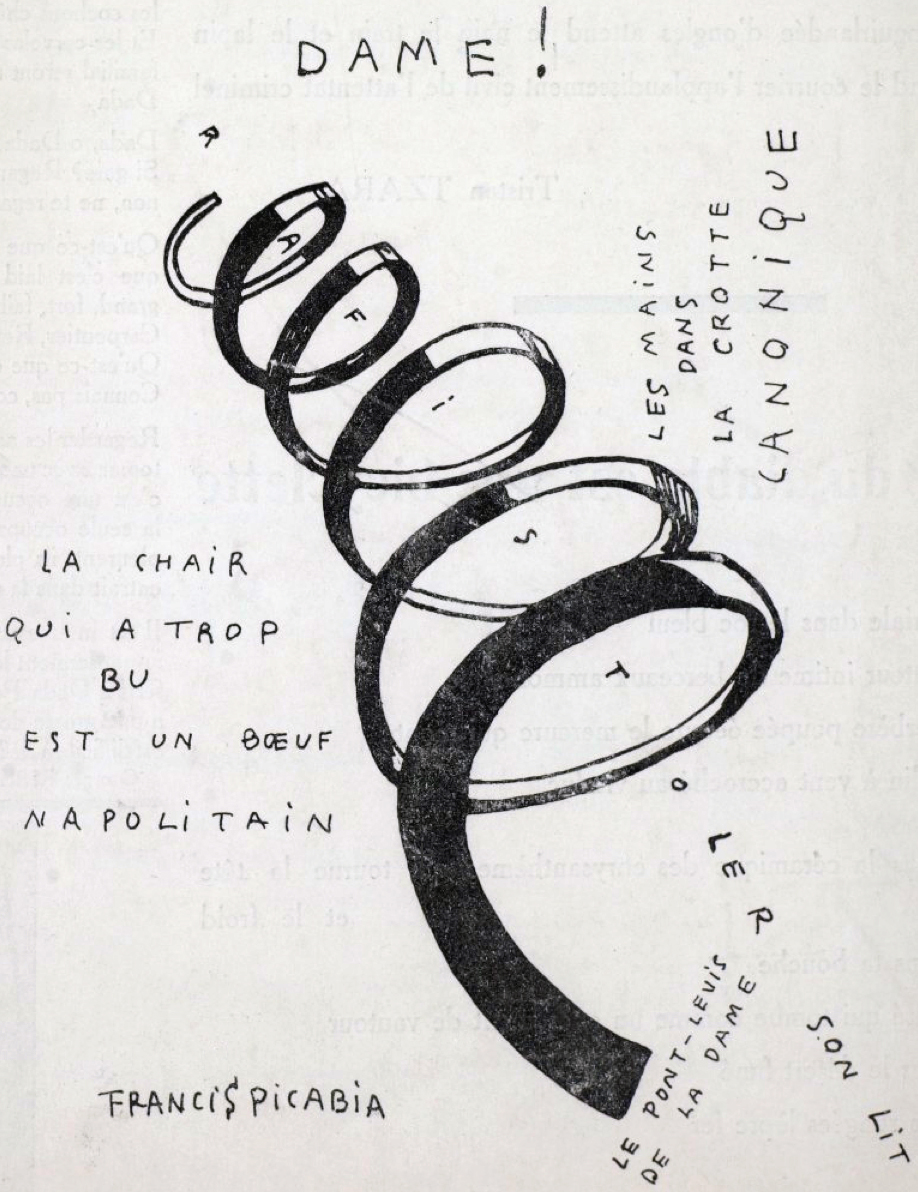

His most significant contribution to the art world was as a central figure in the Dada movement, particularly in its Paris and New York incarnations. Picabia’s Dadaist works were diverse, encompassing a wide range of mediums and styles, from mechanical drawings and abstract paintings to provocative and humorous publications. He was known for his irreverent humor and enjoyed using his art to mock the seriousness of the art world and societal conventions.

One of Picabia’s notable contributions to Dada was through his magazine “391,” which he founded and edited. This publication was instrumental in spreading Dada ideas and aesthetics, featuring contributions from various Dada artists and writers. “391” was a reflection of Picabia’s eclectic and non-conformist approach to art, blending satire, visual innovation, and cultural critique.

Throughout his career, Picabia continued to reinvent his style and approach. After his involvement with Dada, he experimented with different forms of expression, including representational, abstract, and surrealistic styles. His later works, which have been both celebrated and criticized, often confounded critics and the public alike, demonstrating his lifelong commitment to challenging artistic boundaries.

Francis Picabia’s legacy is that of an artistic maverick. His work and life epitomize the spirit of early 20th-century avant-garde movements, particularly his contributions to Dada. Picabia’s constant evolution as an artist and his disdain for artistic conventions have made him a pivotal figure in the study of modern art, influencing generations of artists who seek to challenge and redefine the boundaries of artistic expression.

Different Approaches to Dada

The diversity within this international movement is further exemplified by the variety of approaches across different centers. Zurich, where Dada was founded, was known for its performance art and literary contributions. Berlin Dada, with artists like George Grosz and John Heartfield, took on a more politically charged and confrontational approach, often critiquing the post-war societal and political conditions.

In Paris, Dada had a more conceptual and theoretical bent, as seen in the works of André Breton, who later founded Surrealism. New York Dada, influenced significantly by Duchamp, focused more on the readymade and challenged the conventional boundaries of art through irony and reinterpretation. This geographical diversity within Dada highlights the movement’s broad appeal and its capacity to adapt to different cultural and political contexts.

Spreading the Principles of Dadaism

Club Dada

Club Dada was an informal, avant-garde gathering space and a hub for Dada activities, primarily in Berlin. It was not a club in the traditional sense but more of a conceptual and physical space where Dadaists could meet, collaborate, and perform.

In these settings, artists like George Grosz, John Heartfield, and Hannah Höch, among others, would come together to create, discuss, and exhibit their revolutionary ideas and artworks. These gatherings were characterized by their anarchic spirit and often included public performances, readings, and the display of art that defied traditional norms.

The environment of Club Dada was crucial in fostering the collaborative and interdisciplinary nature of the movement.

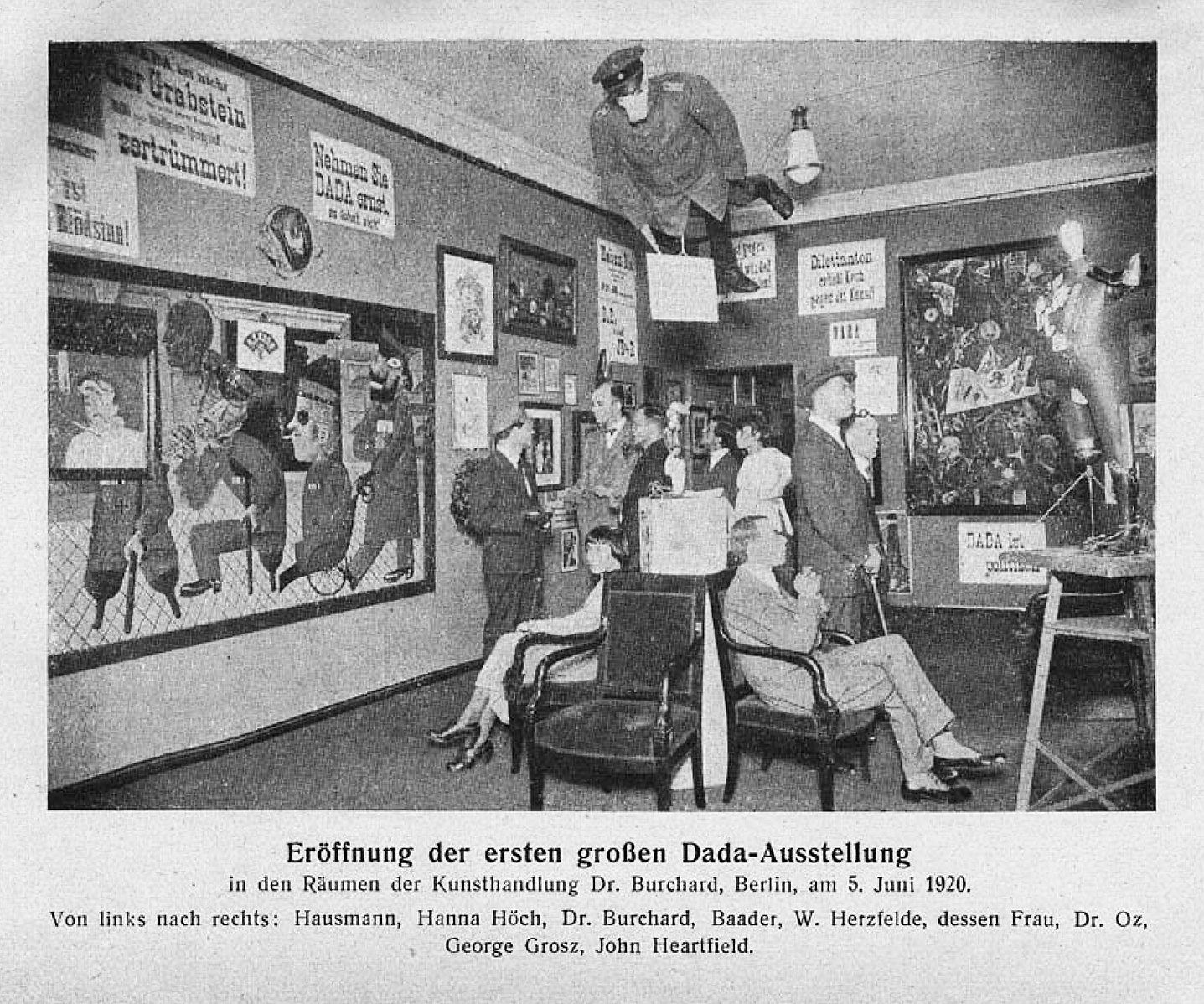

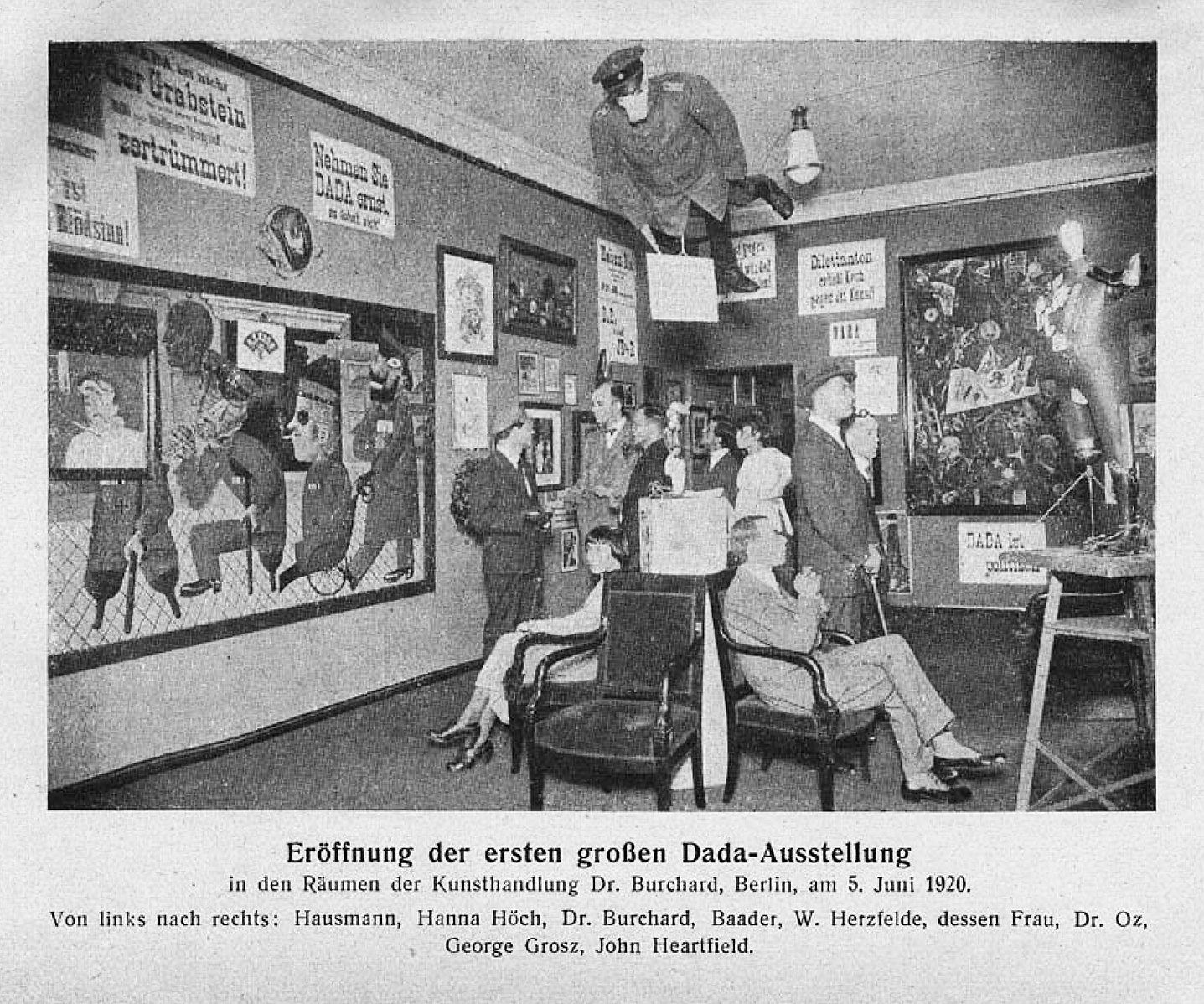

The International Dada Fair (1920)

The International Dada Fair, held in 1920 in Berlin, was one of the most significant and provocative exhibitions in the history of the Dada movement. Organized by key figures like George Grosz, Raoul Hausmann, and John Heartfield, the fair was a seminal event that showcased the diverse and radical nature of Dada art.

The exhibition included a wide range of works, such as photomontages, collages, assemblages, and readymades, that challenged and mocked the established art world and bourgeois society. It was notable for its political content, particularly in its criticism of the Weimar Republic and the aftermath of World War I. The fair was as much a political statement as it was an artistic one, embodying the Dada ethos of subversion and confrontation.

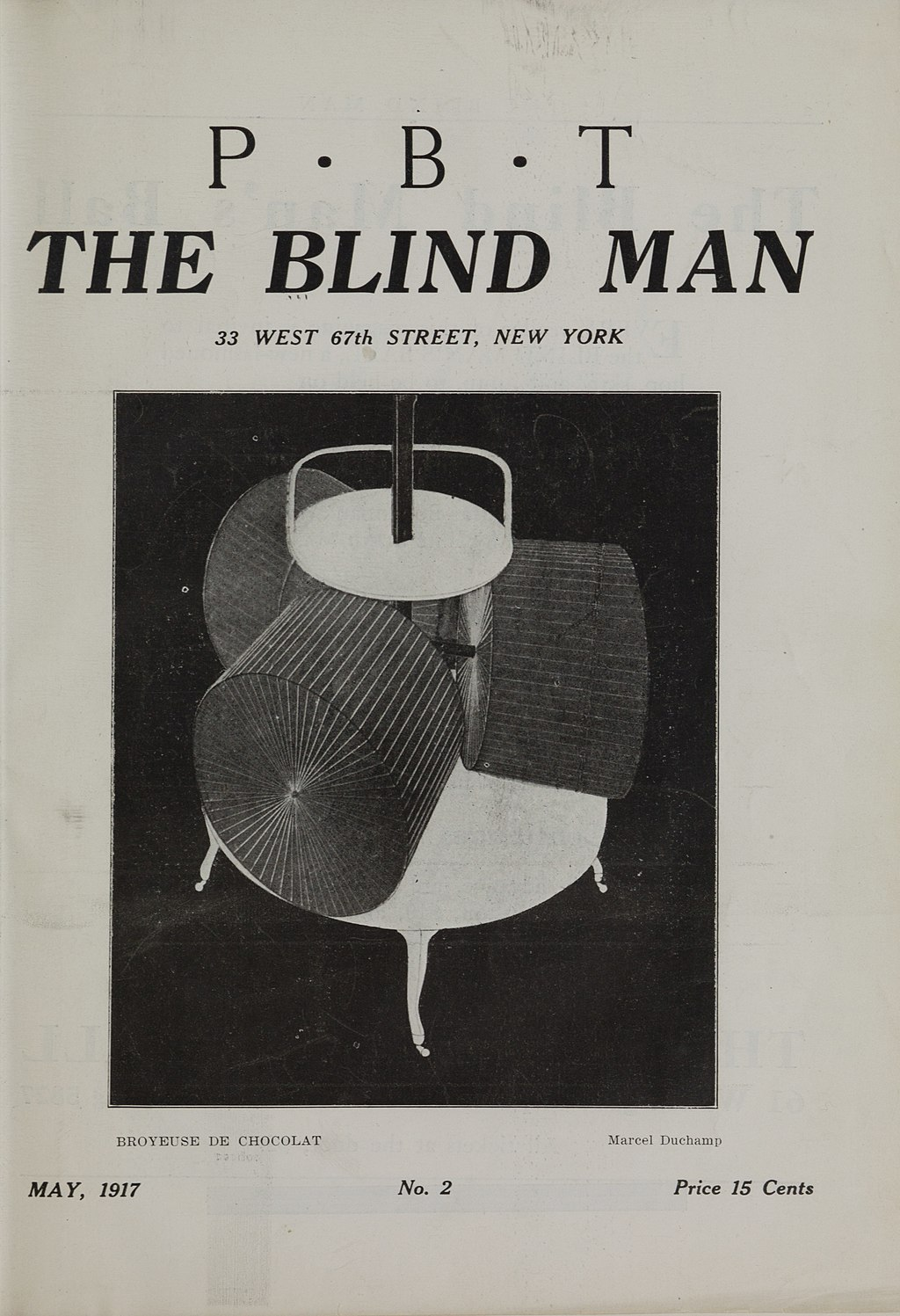

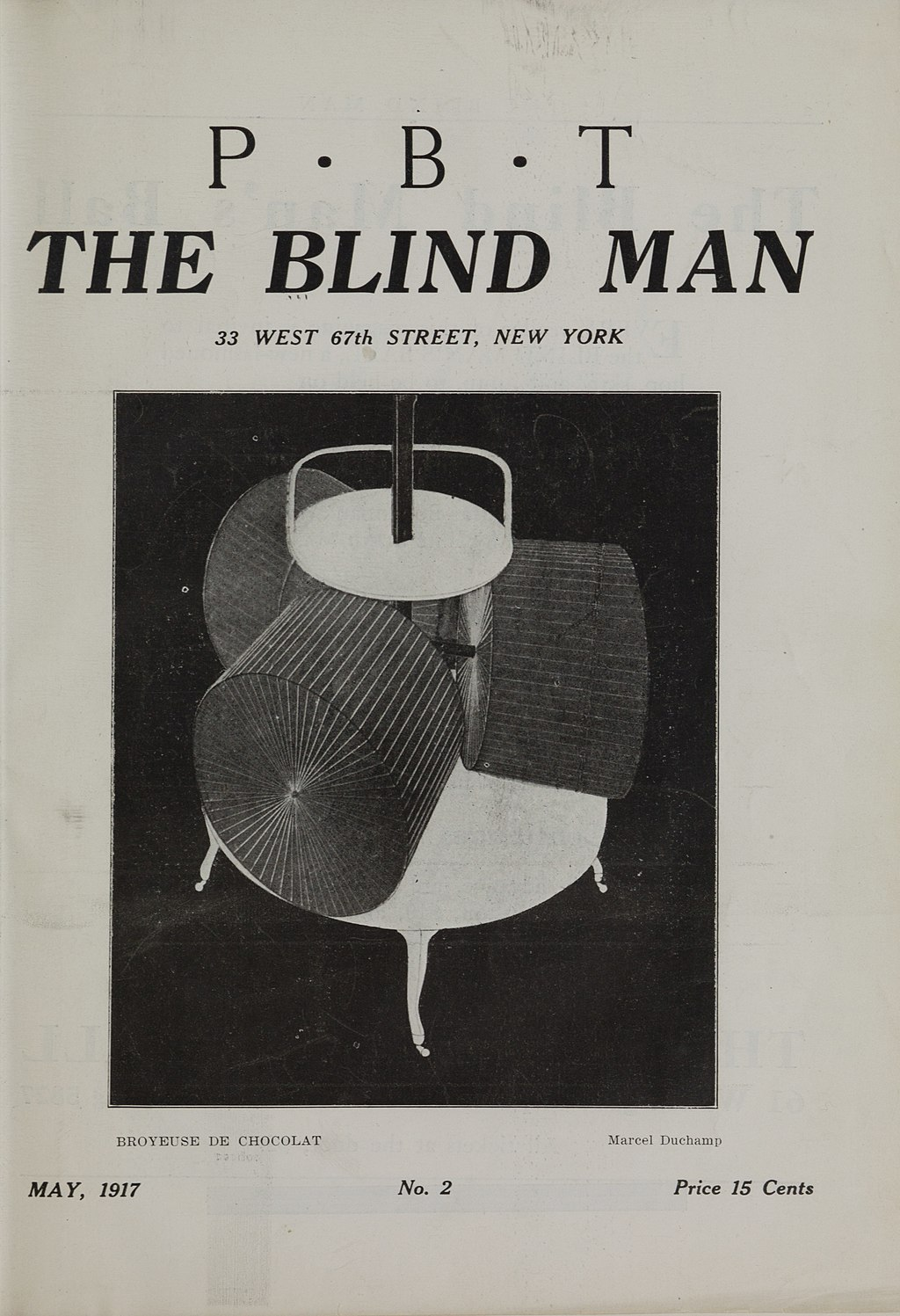

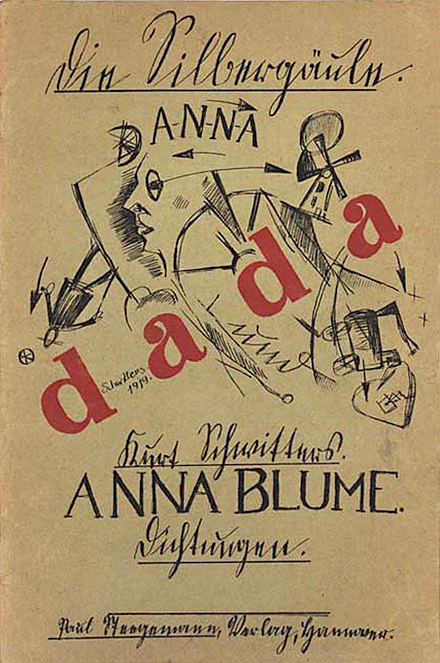

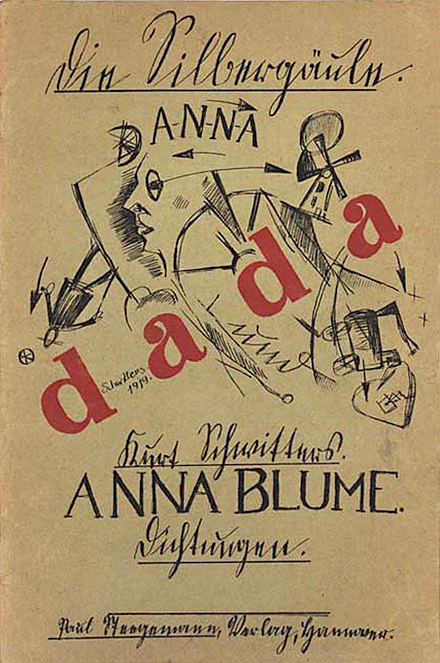

Dada Periodicals

Dada periodicals were a crucial medium for spreading the ideas and aesthetics of the Dada movement. These publications, which included magazines, journals, and pamphlets, were produced in various cities where Dada had a presence, such as Zurich, Berlin, Paris, and New York. Notable among these were “Dada” edited by Tristan Tzara in Zurich, “Die Dada” in Berlin, and “The Blind Man” in New York.

Each Dada periodical was a platform for experimental poetry, provocative essays, absurd artworks, and critical discourses, serving both as artworks themselves and as a means of connecting the disparate Dada communities across Europe and the United States. The irregular and eclectic nature of these publications reflected Dada’s disdain for conventional aesthetics and its embrace of chaos and spontaneity.

Notable Dada Exhibitions

Throughout history, several notable exhibitions have been dedicated to showcasing and exploring the Dada movement. These exhibitions have played a critical role in examining the impact and legacy of Dada, both during its heyday and in more recent times. Some of these exhibitions include:

The First International Dada Fair (1920, Berlin)

This was one of the most significant Dada exhibitions, held in Berlin in 1920. Organized by key Dada artists like George Grosz, Raoul Hausmann, and John Heartfield, this exhibition was a seminal event in the Dada movement, showcasing a wide range of Dadaist art, including photomontages, collages, and readymades.

Dada, 1916-1923 (1953, Sidney Janis Gallery, New York)

This was one of the first major retrospectives of Dada art in the United States. The exhibition included works from many of the key figures of the Dada movement and helped reintroduce Dada to a new generation of artists and art enthusiasts.

Dada and Surrealism Reviewed (1978, Hayward Gallery, London)

This exhibition was a comprehensive look at the Dada and Surrealist movements. It offered a wide-ranging overview of the works and artists involved, and their lasting influence on modern art.

Dada (2005-2006, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris; The National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.; Museum of Modern Art, New York)

This extensive, traveling exhibition was one of the most comprehensive presentations of Dada. It included a vast array of works from different regions where Dada emerged, providing a global perspective on the movement.

Dada’s Women (2009, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven)

This exhibition focused on the often-overlooked contributions of female artists to the Dada movement. It shed light on the works of artists like Hannah Höch, Sophie Taeuber-Arp, and Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven.

Francis Picabia: Our Heads Are Round so Our Thoughts Can Change Direction (2016, Museum of Modern Art, New York)

Although focused on a single artist, this exhibition was crucial in highlighting the role of Francis Picabia in the Dada movement, showcasing his diverse and influential body of work.

These exhibitions, among others, have been instrumental in highlighting the diverse aspects of Dada, its historical context, and its enduring influence on the art world. They have helped to keep the conversation about Dada alive and relevant, allowing new audiences to engage with and understand this pivotal art movement.

Dada’s Influence on Other Art Movements

The impact of Dada extended far beyond its immediate timeline and geographical confines, profoundly influencing subsequent art movements such as Surrealism, Pop Art, and Conceptual Art. Surrealism, which emerged in the 1920s, inherited Dada’s disdain for conventional aesthetics and rationality, but channeled it into a more coherent artistic and literary movement.

André Breton, a key figure in both Dada and Surrealism, carried forward Dada’s spontaneous methods and interest in the irrational, but within a more structured framework that delved into the subconscious and dream imagery. The Surrealist movement’s emphasis on automatism and unexpected juxtapositions owes a significant debt to Dada’s experimental spirit.

Pop Art, which rose to prominence in the 1950s and 1960s, also drew from Dada’s legacy, particularly in its challenge to traditional distinctions between ‘high’ and ‘low’ art. Dada’s use of everyday objects and popular imagery laid the groundwork for Pop Art’s incorporation of commercial and popular culture, as seen in the works of artists like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein. The irreverence and satire prevalent in Dada found a new expression in Pop Art’s critique of consumerism and mass media.

Conceptual Art, emerging in the 1960s, took Dada’s questioning of the material aspects of art to its logical conclusion. Conceptual artists, much like the Dadaists, often downplayed the importance of the art object, focusing instead on the idea or concept behind the work. This philosophical shift, which questioned the very nature of what constitutes art, is a direct extension of the intellectual provocations initiated by Dada.

Exploration of Dada’s Role in Reshaping Art

Dada’s role in challenging and reshaping the future of art was particularly significant in the realms of abstract and conceptual thinking. By liberating art from traditional constraints and expectations, Dada opened up new possibilities for artistic expression.

It encouraged a form of abstraction that was not just visual, but conceptual, allowing artists to express complex ideas through unconventional means. This freedom of thought and expression paved the way for a more expansive and inclusive understanding of what art could be, influencing countless artists and movements in its wake.

Dada’s Impact on Modern Art Theories and Practices

The impact of Dada on modern art theories and practices is substantial. It introduced a critical perspective that questioned the role and purpose of art in society. The movement’s emphasis on chance, spontaneity, and the rejection of established artistic standards forced a reevaluation of the creative process itself.

Dada’s legacy in art theory is also marked by its challenge to the traditional notion of the artist as a skilled creator of aesthetically pleasing objects. Instead, Dada posited the artist as an innovator and provocateur, roles that have become central in contemporary artistic discourse.

The movement’s radical approach and its challenges to artistic conventions continue to inspire and influence modern and contemporary art, making its study essential for understanding the evolution of artistic thought and practice in the 20th and 21st centuries.

Dada’s Legacy and Contemporary Relevance

The enduring legacy of Dada in contemporary art and culture is profound and multifaceted. Its influence extends beyond specific artistic techniques or styles, permeating the very approach and philosophy towards art.

Contemporary art, with its diverse and often unconventional expressions, owes much to Dada’s initial rebellion against traditional art forms. The movement’s pioneering spirit in embracing absurdity, randomness, and the integration of everyday objects into art has been a continuous source of inspiration.

This is evident in the variety of contemporary artworks that challenge viewers’ perceptions and expectations, much in the spirit of Dada.

How Contemporary Artists Continue to Draw on Dadaist Principles

Contemporary artists draw inspiration from Dada’s principles in numerous ways. The movement’s emphasis on spontaneity and the use of chance in the creative process has been particularly influential.

Many modern artists adopt these methods to produce works that are unpredictable and challenge conventional artistic processes. Additionally, the Dadaists’ use of readymades has found resonance in contemporary art, where objects from everyday life are often repurposed to create new meanings and commentaries on various aspects of modern society.

The legacy of Dada’s performance art is also evident today, with performance being a key medium for many artists seeking to engage with their audience in more interactive and thought-provoking ways.

Ongoing Relevance of Club Dada Artists

The ongoing relevance of Dada in challenging societal and artistic norms cannot be overstated. In a contemporary context, where art is continually evolving and responding to a rapidly changing world, Dada’s example remains pertinent.

The movement’s original challenge to the status quo and its questioning of what constitutes art are questions that continue to animate artistic discourse. Moreover, Dada’s critique of societal norms and conventions finds a parallel in contemporary art’s engagement with issues such as consumerism, political unrest, and social inequalities.

This continued relevance underscores the importance of Dada not just as a historical movement, but as an enduring source of inspiration and provocation in the ever-evolving landscape of art and culture.

Final Thoughts on Dada Ideas, Artists, and Influence on Other Movements

The Dada movement, emerging amidst the chaos of World War I, marked a pivotal moment in the history of art. Its radical approach, characterized by an embrace of the absurd, the rejection of conventional aesthetic standards, and the use of innovative mediums, challenged the very foundations of artistic creation.

Dada’s influence extended far beyond its initial milieu, leaving an indelible imprint on both its contemporaries and subsequent generations of artists. The movement’s legacy, evident in the development of key art movements such as Surrealism, Pop Art, and Conceptual Art, highlights its role as a catalyst for change and experimentation in the arts.

Understanding Dada is thus essential in comprehending the broader narrative of modern and contemporary art, where the questioning of norms and the continuous redefinition of artistic boundaries remain central themes. The Dada movement, with its blend of irreverence and profound philosophical inquiry, continues to be a touchstone for artists seeking to explore the limits and possibilities of artistic expression.

Design Dash

Join us in designing a life you love.

-

All About Our 7-Day Focus & Flex Challenge

Sign up before August 14th to join us for the Focus & Flex Challenge!

-

Unique Baby Names Inspired by Incredible Women from History

Inspired by historic queens, warriors, artists, and scientists, one of these unusual baby names might be right for your daughter!

-

Finding a New 9 to 5: How to Put Freelance Work on a Resume

From listing relevant skills to explaining your employment gap, here’s how to put freelance jobs on your resume.

-

What is Generation-Skipping, and How Might it Affect Sandwich Generation Parents?

The emotional pain and financial strain of generation skipping can be devastating for Sandwich Generation parents.

-

Four Material Libraries Dedicated to Sustainability, Preservation, and Education

From sustainable building materials (MaterialDriven) to rare pigments (Harvard), each materials library serves a specific purpose.

-

Do You Actually Need a Beauty Fridge for Your Skincare Products? (Yes and No.)

Let’s take a look at what dermatologists and formulators have to say about whether your makeup and skincare belong in a beauty fridge.