Augusta Savage: The Harlem Renaissance Sculptor Who Fought for Equal Rights in the Arts

Summary

Reflection Questions

Journal Prompt

Augusta Savage was an important sculptor and activist during the Harlem Renaissance, an era noted for its cultural, social, and artistic explosion among African-American communities in the 1920s and 1930s. Savage’s work not only exemplified the dynamic artistic innovation of this period but also symbolized a relentless struggle for racial and gender equality within the arts. Her contributions extended beyond her sculptural creations, as she actively advocated for the recognition and support of African-American artists, challenging the prevailing barriers of segregation and discrimination. Below, we explore Savage’s life, her impactful artistic journey, and her enduring legacy as a champion of equal rights in the arts.

Early Life and Education

Augusta Savage was born Augusta Christine Fells on February 29, 1892, in Green Cove Springs, about 250 miles from West Palm Beach, Florida. The seventh of fourteen children, she was raised in a time and place where opportunities for African Americans, especially women, were severely limited. Her early life in the South was marked by the harsh realities of racial segregation and economic hardship. Despite these challenges, Savage’s childhood was pivotal in shaping her artistic journey. The natural environment of Florida and her experiences within her community played a significant role in her early artistic expression.

Early Encounters with Art and Initial Challenges Due to Race and Gender

Savage’s artistic talent became evident in her childhood, where she displayed a natural inclination towards sculpting, using the clay that was abundant in her local environment. However, her early attempts at pursuing art were met with resistance.

Her father, a Methodist minister, initially disapproved of her art, viewing it as a sinful practice. Furthermore, her aspirations were dampened by the racial and gender prejudices of the time. In her early years, Savage applied to the Palm Beach County Fair and was rejected because of her race. These experiences of racial and gender-based discrimination were defining moments that shaped her later activism in the arts.

Savage’s Young Adulthood

In her late teens, Augusta Savage married John T. Moore in 1907. This marriage was relatively brief, as Moore died a few years later, leaving Savage a young widow. She bore a child during this marriage, Irene Connie Moore, who was born in 1909.

After the death of her first husband, Savage married James Savage in 1915. This second marriage marked a significant period in her life, as it was after this that she took the surname “Savage” which she retained throughout her career. However, this marriage too was short-lived and ended in divorce. She married once more in 1923.

Savage’s young adult life, including her experiences with marriage and early struggles, played a crucial role in shaping her both personally and as an artist. Her resilience in the face of personal adversity and societal challenges set the stage for her later accomplishments as an artist and activist in the Harlem Renaissance and beyond.

Move to New York City and Enrollment at Cooper Union

Following the end of her second marriage in 1921, Savage moved to New York City, a significant turning point in her life and career. New York, particularly Harlem, was a hub for African-American culture and intellectual activity, later known as the Harlem Renaissance.

Fuel your creative fire & be a part of a supportive community that values how you love to live.

subscribe to our newsletter

Savage enrolled in the prestigious Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, a college known for its progressive stance on education and its commitment to admitting students solely based on merit. She excelled academically and artistically, completing the four-year course in just three years. Her time at Cooper Union not only honed her skills as a sculptor but also exposed her to a broader spectrum of artistic styles and philosophies, which she later incorporated into her work.

Savage’s early life and education laid the foundation for her artistic pursuits and her later role as an advocate for equal rights in the arts. Her journey from the clay soils of Florida to the bustling streets of New York City symbolizes a transition from constrained beginnings to expansive possibilities, reflecting the broader aspirations and struggles of African-American artists during the early 20th century.

Artistic Career and Major Works

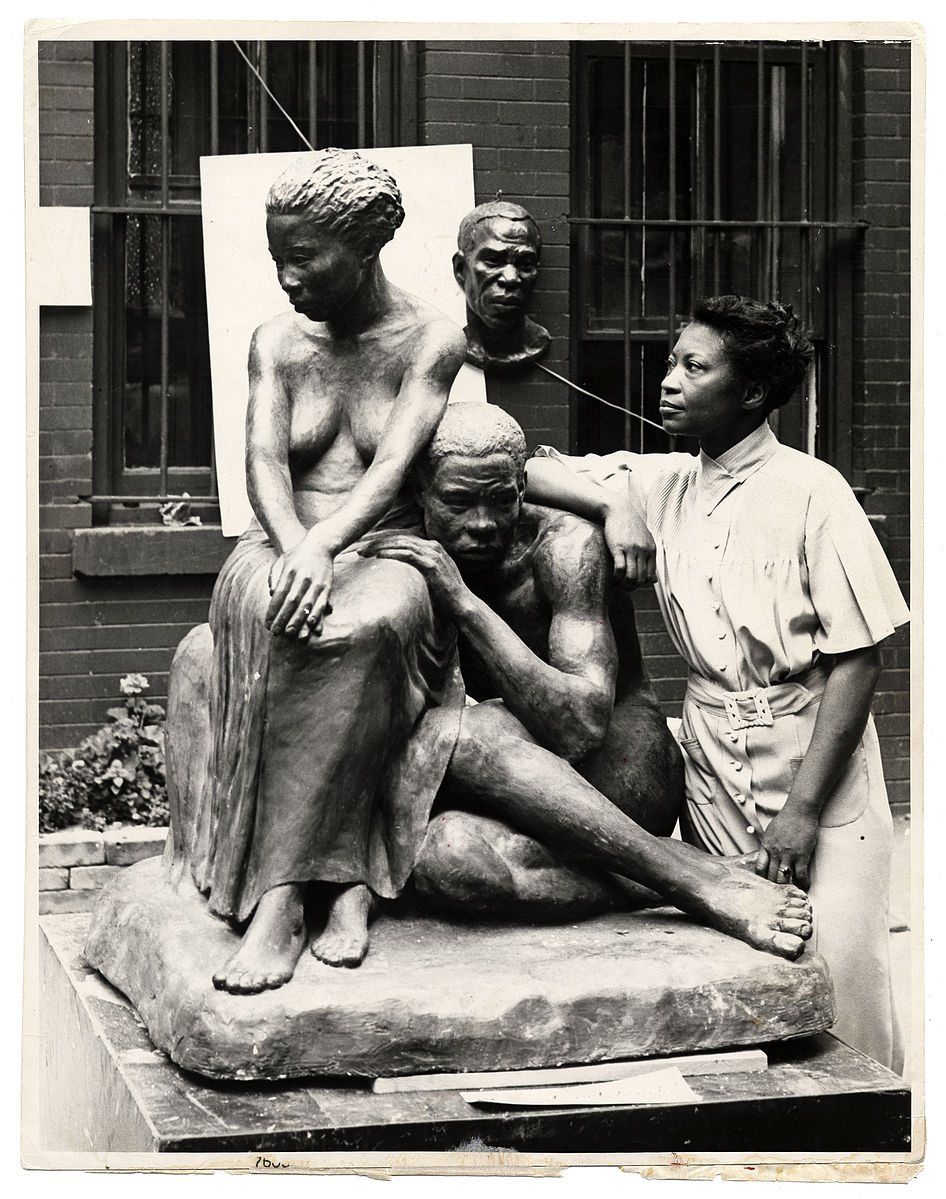

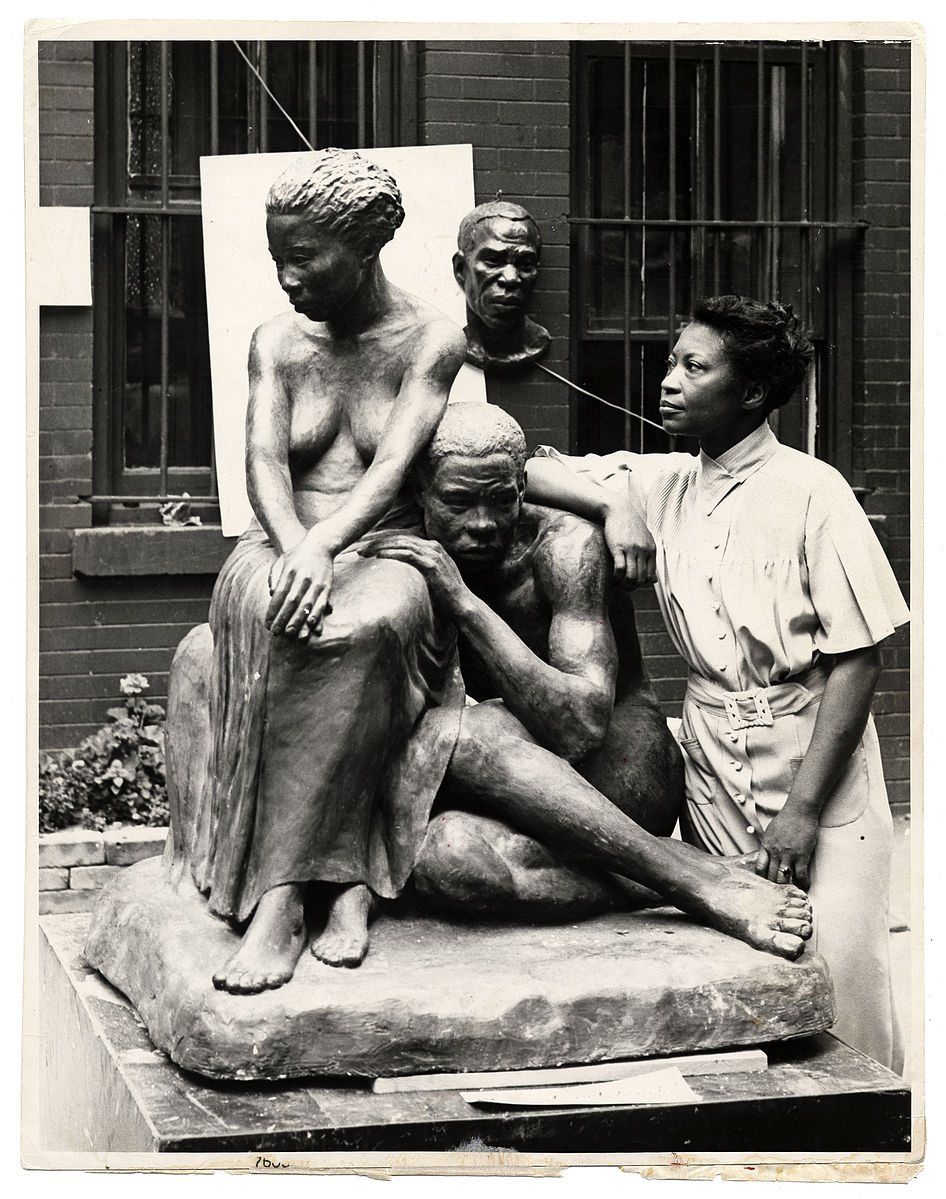

Augusta Savage’s artistic style was characterized by a blend of realism and Harlem Renaissance aesthetics, focusing on themes of social justice, racial identity, and community. Her choice of medium predominantly revolved around sculpting in clay, which was later cast in plaster or bronze.

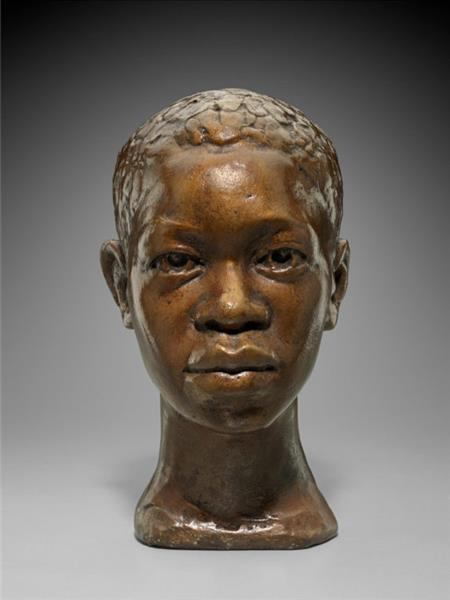

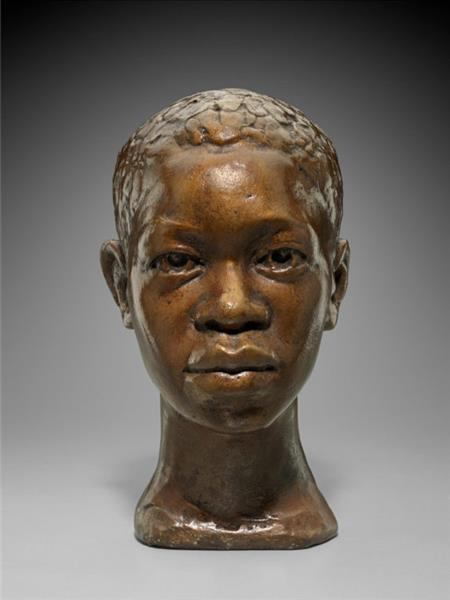

Savage’s work often featured portraits and busts, capturing both the physical likeness and the intrinsic character of her subjects. Her ability to imbue her sculptures with emotional depth and a sense of realism was a hallmark of her style. This realism was not just in physical likeness but in capturing the essence and experiences of African Americans during the early 20th century.

A Selection of Notable Works

Among Savage’s most celebrated works is “The Harp,” inspired by the spiritual “Lift Every Voice and Sing.” Created for the 1939 New York World’s Fair, it depicted African American youth as the strings of a harp, with a hand of God at the base, symbolizing unity and aspiration.

Another significant work, “Gamin,” an affectionate portrayal of a streetwise young African American boy, showcased her skill in capturing both physical likeness and the subject’s personality. “Gamin” is particularly notable for its blend of artistry and social commentary, reflecting the everyday experiences of African Americans.

Important Augusta Savage Sculpture Commissions

Savage received several important commissions throughout her career, which were both a testament to her artistic prowess and her growing influence in the art world. One such commission was for the 1934 World’s Fair, where she created a bust of W.E.B. Du Bois, a leading African-American intellectual of the time. Her ability to secure such commissions, despite the racial barriers of the period, was a significant achievement and a step forward in the recognition of African-American artists.

Exhibitions and Reception during the Harlem Renaissance

During the Harlem Renaissance, Savage’s work was featured in several key exhibitions, which were instrumental in bringing Black art into the broader American cultural landscape. Her participation in these exhibitions not only showcased her artistic talent but also helped to challenge the racial prejudices of the art world.

The reception to the work of sculptor Augusta Savage was generally positive, with critics praising her ability to capture the nuances of African-American life and identity. Her exhibitions were not only displays of artistic talent but also powerful statements in the fight for racial equality and the recognition of African-American art. Although she was a prominent figure, many of her works were not preserved, and she faced significant financial and logistical challenges. This affected her ability to maintain a lasting public presence in the art world during her lifetime. Her work was more greatly appreciated posthumously.

Savage’s artistic career was a profound blend of skill, expression, and activism. Her works, whether they were intimate busts or large-scale public sculptures, not only displayed her exceptional talent but also her commitment to using art as a medium for social change. Her legacy in the realm of sculpture is marked not only by her unique artistic style but also by her relentless pursuit of equality and representation for African-American artists.

Activism and Advocacy for Equal Rights

Augusta Savage’s activism extended beyond her sculptures, as she was deeply involved in advocating for the rights and recognition of African American artists. She was acutely aware of the financial and social barriers that hindered artists of color and sought to address these challenges.

Savage lobbied tirelessly for funding, both public and private, to support African-American artists. She was instrumental in urging the Works Progress Administration (WPA) to hire more African American artists during the Great Depression, ensuring that they received both financial support and a platform to showcase their work. Her efforts led to greater visibility and opportunities for many artists in a time of widespread racial discrimination.

Founding of the Savage Studio of Arts and Crafts

In 1932, Savage founded the Savage Studio of Arts and Crafts in Harlem, a significant milestone in her career as an activist and educator. This studio served as a school and workshop where young African American artists could hone their skills, find support, and express themselves creatively.

The studio was not just a place of learning; it was a haven that fostered a sense of community and belonging among artists who were often marginalized in mainstream art spaces. Through this initiative, Savage directly contributed to the nurturing and development of the next generation of African American artists.

Founding of the Harlem Community Arts Center

The Harlem Community Arts Center (HCAC) was established in the 1930s as part of the Federal Art Project, a New Deal program. Augusta Savage was instrumental in its founding and became its first director. The center was a hub for artistic education and cultural activity in Harlem.

Under Savage’s leadership, the HCAC provided free art classes to the Harlem community, including drawing, painting, and sculpting. The center was more than an educational institution; it was a space where African Americans could explore and express their artistic talents during a time when racial discrimination and economic hardship were prevalent. The center attracted many aspiring artists and played a crucial role in nurturing the talents of future luminaries in African American art.

Savage’s work at the Harlem Community Arts Center is remembered for its profound impact on the Harlem community and the broader landscape of African American art. The center not only nurtured individual talents but also fostered a sense of community and solidarity among African American artists.

Role as a Mentor and Influence on Future Generations of Artists

Savage’s role as a mentor was perhaps one of her most enduring contributions to the arts. She nurtured the talents of several young artists who would go on to achieve significant acclaim, including Jacob Lawrence and Gwendolyn Knight. Her guidance was not limited to technical skills; she also imparted lessons on resilience and perseverance in the face of adversity.

Savage’s influence extended well beyond her lifetime, as many of her students continued to propagate her teachings and values in their own careers and mentorship roles. Her legacy as a mentor and advocate highlights her profound impact on the African American art community and her pivotal role in shaping its future.

Through her activism, Augusta Savage not only carved a space for African-American artists in the art world but also laid a foundation for future generations. Her efforts in securing funding, creating educational opportunities, and mentoring young artists were instrumental in the fight for racial equality in the arts. Savage’s dedication to this cause was a testament to her belief in the power of art as a tool for social change and her commitment to ensuring that African American voices were heard and valued in the artistic narrative.

Challenges and Obstacles

Augusta Savage’s journey as an artist and activist was fraught with challenges, chief among them being the pervasive racism and sexism of her time. The early 20th century art world was largely dominated by white males, leaving little room for African American women artists like Savage. She faced systemic barriers in gaining recognition and opportunities, with many art schools, galleries, and patrons often denying her access purely based on her race and gender. This discrimination was not just a matter of social exclusion but also a significant barrier to professional development and financial stability.

Specific Incidents that Highlight the Struggles She Faced

One of the most notable incidents highlighting the challenges Savage faced occurred during her application for an international fellowship from the French government. Despite her evident talent and the quality of her work, Savage was denied the fellowship due to the objections of some Southern committee members who feared that her success would inspire other African-Americans.

This denial was a stark reminder of the racial prejudice that permeated even the highest levels of the art world. This event was a pivotal point that galvanized her advocacy efforts.

Another significant incident was the destruction of her most famous work, “The Harp,” after the 1939 New York World’s Fair, due to lack of funds to cast it in bronze or store it. This loss was a bitter symbol of the financial and logistical constraints that often hindered Black artists. For Savage, this was not an isolated event. Many of her sculptures faced similar fates, which speaks to broader issues of systemic neglect and the impermanence of her medium (primarily plaster), which was less durable and less likely to be preserved than bronze.

Impact of These Challenges on Her Career and Personal Life

The cumulative impact of these challenges on Savage’s career and personal life was profound. Professionally, these obstacles limited her ability to achieve the same level of fame and financial success as her white counterparts.

They also meant that much of her work, including some of her most significant sculptures, was not preserved for future generations. On a personal level, these continual battles against racism and sexism took a toll on Savage. Despite her resilience and determination, she experienced periods of financial hardship and emotional strain, which were compounded by the responsibility she felt to support and advocate for other African-American artists.

Augusta Savage’s experience with racism and sexism in the art world is a poignant reminder of the systemic barriers that artists of color, particularly women, have faced throughout history. Her struggles and the impact they had on her life and work underscore the importance of her achievements and the resilience she displayed in overcoming these obstacles. Her story is not only a testament to her individual talent and determination but also a reflection of the broader challenges faced by African-American artists in the United States.

Pioneering Achievements

Augusta Savage was among the first African American female artists to gain international recognition for her work, particularly for her sculptures which showcased both artistic skill and a deep understanding of the African American experience.

Savage opened her own art gallery, which was a rare achievement for an African-American woman during that era. This gallery not only showcased her works but also provided a platform for other African-American artists.

As the director of the Harlem Community Arts Center, Savage became the first African-American artist and woman to lead a significant Federal Art Project institution. Her role in this position marked a significant milestone in the inclusion and recognition of African Americans in federally funded art programs.

Augusta Savage’s involvement with the Harlem Community Art Center and her pioneering achievements as an African-American woman in the arts field reflect her dedication to art, education, and racial equality. Her legacy continues to inspire and influence artists and communities, exemplifying the power of art as a tool for social change and empowerment.

Later Life

Augusta Savage moved to the Catskills later in her life after a series of career upsets, including the loss of her job at the Harlem Community Art Center. After a significant but later stunted career in New York during the Harlem Renaissance, where she achieved considerable acclaim as an artist and educator, Savage left the city to spend time with family and work on her writing career.

However, Savage eventually returned. She passed away in New York City due to cancer shortly thereafter. By the time of her death in 1962, her artistic career and recognition had fallen off. According to the Smithsonian, “she died in relative obscurity.”

Legacy and Influence

Augusta Savage’s contributions during the Harlem Renaissance significantly impacted both the movement and the broader landscape of African-American art. Her work, characterized by its blend of realism and expressiveness, provided a nuanced representation of African-American life and identity, challenging the prevailing stereotypes of the era.

Savage’s role extended beyond her artistic creations; she was a central figure in the Harlem Renaissance, fostering a community of artists and serving as a mentor to emerging talents. Her studio became a crucible for artistic development and a symbol of the possibilities for African-American artists. Through her advocacy and mentorship, she helped lay the groundwork for the future of African-American art, paving the way for generations of artists.

Recognition and Revival of Interest in Her Work in Recent Years

In recent years, there has been a significant revival of interest in Augusta Savage’s work and legacy. This resurgence is partly due to a broader societal shift towards recognizing and valuing the contributions of historically marginalized artists.

Museums, art historians, and cultural institutions have begun to acknowledge her role in American art history more prominently. Exhibitions and retrospectives dedicated to her work have brought her contributions back into public view, allowing a new generation to appreciate her artistry and understand her impact. This renewed interest not only celebrates Savage’s artistic achievements but also reaffirms the importance of her activism and advocacy for racial equality in the arts.

Institutions with Substantial Collections of Her Work

Augusta Savage’s work is held in the collections of several notable museums, reflecting her significant contribution to American art and the Harlem Renaissance. Some of these museums include the Met, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

As part of the New York Public Library, the Schomburg Center holds significant materials related to Savage and her work. This includes not only her artistic creations but also archival materials that provide insight into her life, career, and the broader context of African-American art during the Harlem Renaissance.

The Schomburg Center’s collection is vital for understanding Savage’s impact and legacy. It serves as a resource for researchers, scholars, and the public who are interested in exploring the life and work of this influential artist and activist. The inclusion of her work and related materials in the Schomburg Center’s collection highlights the importance of preserving the history and contributions of African-American artists and their role in shaping American art and culture.

Influence on Contemporary Artists and the Ongoing Fight for Equality in the Arts

Augusta Savage’s influence extends into the contemporary art world, where her legacy continues to inspire and inform artists and activists alike. Her story of resilience in the face of adversity and her commitment to social justice resonate with many contemporary artists who navigate similar challenges. Her role as a mentor and advocate is particularly relevant today, as discussions around representation and diversity in the arts gain prominence.

Savage’s life and work serve as a powerful example of how art can be a vehicle for social change, encouraging contemporary artists to use their platforms to address social issues and advocate for equality. Her enduring influence is a testament to her vision of an inclusive and equitable art world, a vision that continues to inspire the ongoing fight for equality in the arts.

Augusta Savage’s legacy in the art world is multifaceted, encompassing her artistic achievements, her role in the Harlem Renaissance, and her enduring impact on the fight for equality in the arts. Her life and work continue to inspire and influence artists and activists, serving as a powerful reminder of the role of art in social change and the importance of advocating for underrepresented voices in the cultural narrative.

Final Thoughts on Augusta Savage’s Life and Work

Augusta Savage’s enduring legacy in the realms of art and civil rights is marked by her profound contributions to the Harlem Renaissance and her tireless advocacy for African-American artists. Her work not only broke new ground in artistic expression but also challenged the societal barriers of racism and sexism.

The relevance of Savage’s story in contemporary society is unmistakable, offering valuable insights into the ongoing struggles for equality and representation in the arts. Her life and all the art she created serve as a beacon of resilience and determination, inspiring current and future generations to continue the pursuit of equity and justice.

For those interested in delving deeper into Savage’s life and the broader context of the Harlem Renaissance, recent books by Black authors offer enriching perspectives. Titles such as Augusta Savage: Renaissance Woman by Jeffreen M. Hayes, and Harlem Renaissance Lives from the African American National Biography edited by Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, provide comprehensive accounts of her life and the era she helped define.

These works not only celebrate Savage’s artistic achievements but also contextualize her in the larger narrative of African-American history and culture.

Design Dash

Join us in designing a life you love.

-

All About Our 7-Day Focus & Flex Challenge

Sign up before August 14th to join us for the Focus & Flex Challenge!

-

Unique Baby Names Inspired by Incredible Women from History

Inspired by historic queens, warriors, artists, and scientists, one of these unusual baby names might be right for your daughter!

-

Finding a New 9 to 5: How to Put Freelance Work on a Resume

From listing relevant skills to explaining your employment gap, here’s how to put freelance jobs on your resume.

-

What is Generation-Skipping, and How Might it Affect Sandwich Generation Parents?

The emotional pain and financial strain of generation skipping can be devastating for Sandwich Generation parents.

-

Four Material Libraries Dedicated to Sustainability, Preservation, and Education

From sustainable building materials (MaterialDriven) to rare pigments (Harvard), each materials library serves a specific purpose.

-

Do You Actually Need a Beauty Fridge for Your Skincare Products? (Yes and No.)

Let’s take a look at what dermatologists and formulators have to say about whether your makeup and skincare belong in a beauty fridge.