Ukiyo-e Evolution: Japanese Woodblock Printing Then and Now

Summary

Reflection Questions

Journal Prompt

From its Buddhist beginnings in ancient Japan to its modern-day resurgence, the evolution of Japanese woodblock printing is steeped in artistic innovation, cultural exchange, and enduring legacy. Rooted in centuries-old traditions yet continually adapted to suit the changing tastes and technologies of each era, this time-honored technique has left an indelible mark on the world of art and printmaking. Known as ukiyo-e, Japanese woodblock printing flourished during the Edo period, capturing the essence of daily life, entertainment, and the natural world with unparalleled beauty and craftsmanship. Over the centuries, ukiyo-e prints not only shaped the aesthetic sensibilities of Japanese society but also sparked fascination and inspiration across the globe, influencing Western artists from Vincent van Gogh to contemporary masters like Takashi Murakami. Today, the legacy of woodblock printing endures, as artists continue to explore its rich potential and push the boundaries of tradition in search of new artistic horizons. Read on to learn all about the evolution of ukiyo-e.

Japanese Woodblock Printing Then: Exploring the Origins of Ukiyo-e

According to this resource from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Woodblock prints were initially used as early as the eighth century in Japan to disseminate texts, especially Buddhist scriptures.” During this period, woodblock printing played a crucial role in the spread of knowledge and religious teachings, allowing for the mass production of texts and images.

However, it was not until the Edo period (1603-1868) that woodblock printing truly flourished as an art form with the rise of ukiyo-e. This artistic movement brought about a shift in focus from religious and literary texts to images depicting the secular pleasures and pursuits of the urban populace. Therefore, while woodblock printing has ancient origins in Japan, its development into the vibrant and influential art form of ukiyo-e occurred during the early modern period.

Japanese Prints during the Edo Period

In the early 17th century, Asian art changed forever with the introduction of new woodblock printing techniques, catalyzing the birth of a new artistic movement known as ukiyo-e, or “pictures of the floating world.” Initially influenced by Chinese printing methods, Japanese artisans quickly adapted and refined the process to suit their own cultural and aesthetic sensibilities. The term “ukiyo” referred to the transient, pleasure-seeking lifestyle of the urban populace, particularly in Edo (modern-day Tokyo), where theaters, teahouses, and pleasure quarters flourished.

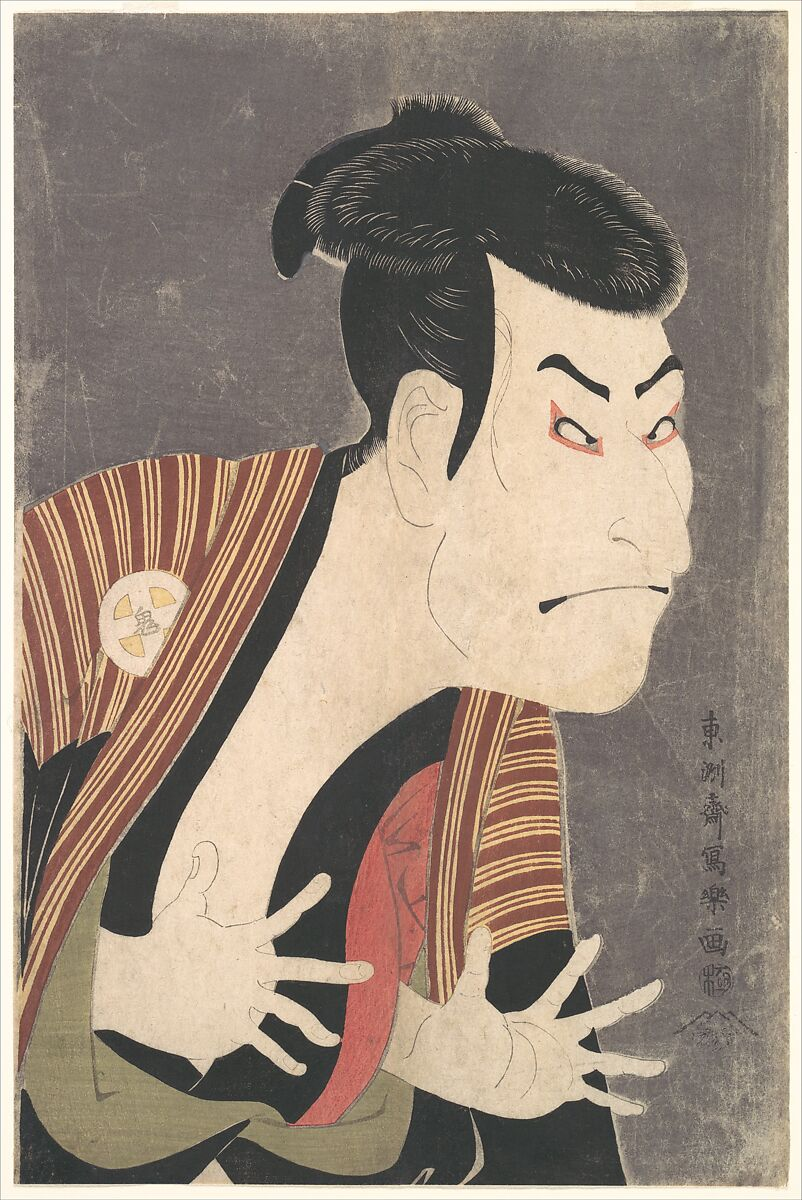

The ukiyo e style emerged as a reflection of this vibrant urban culture, depicting scenes of kabuki actors, courtesans, landscapes, and everyday life. Artists such as Hishikawa Moronobu and Suzuki Harunobu were among the pioneers who popularized such creative prints during this formative period, laying the groundwork for its subsequent development and widespread appeal throughout the Edo period.

The Golden Age of Japanese Woodblock Prints

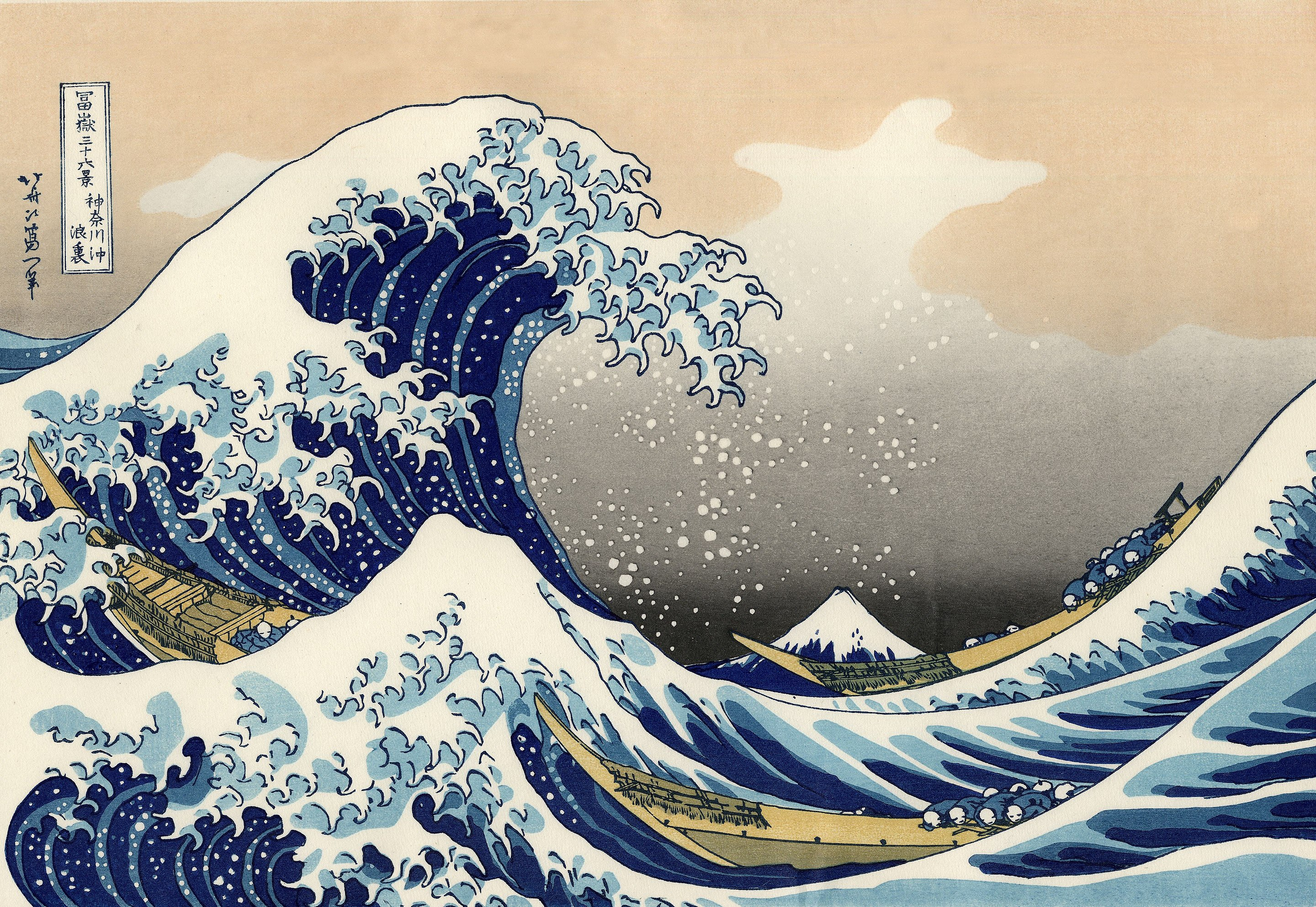

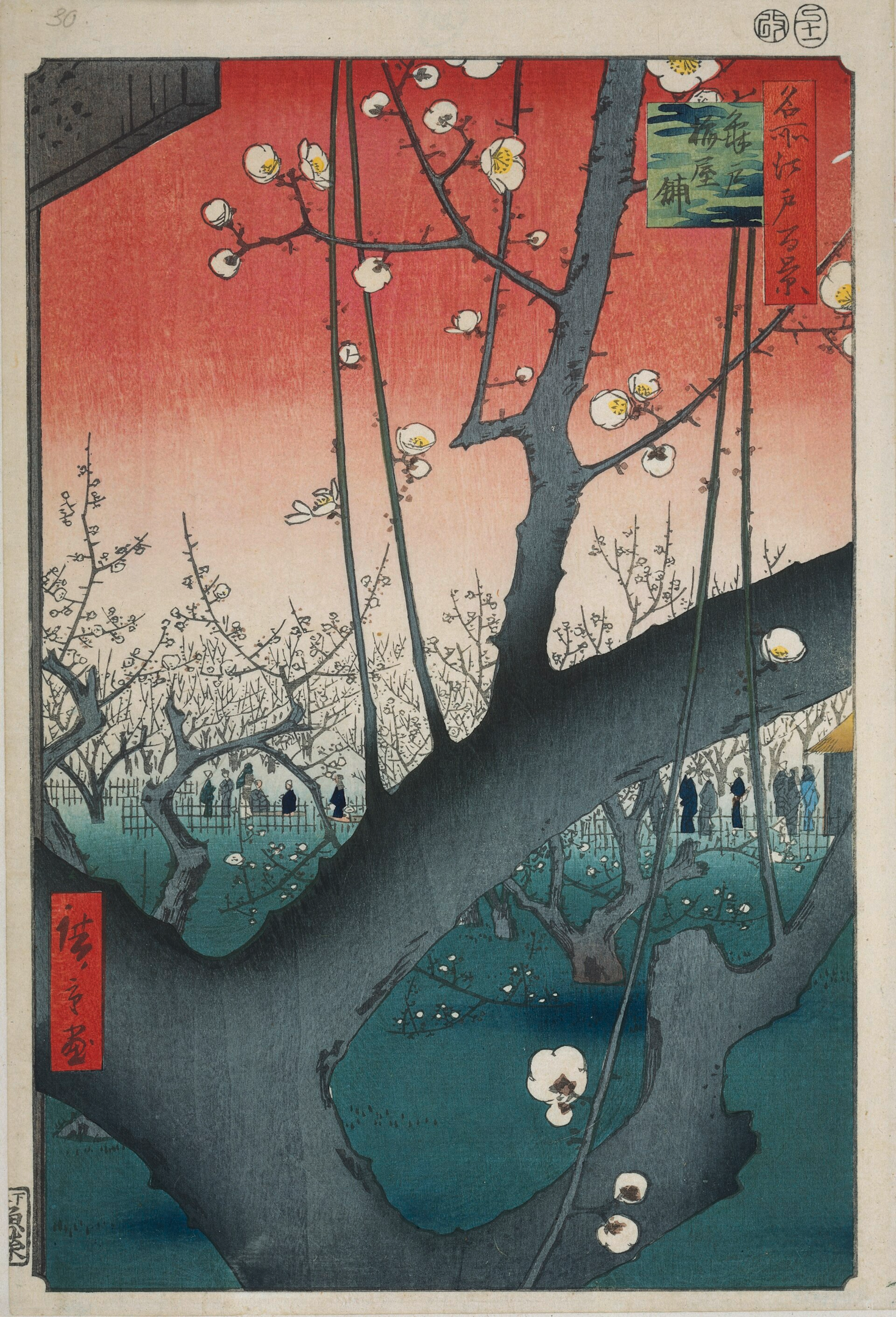

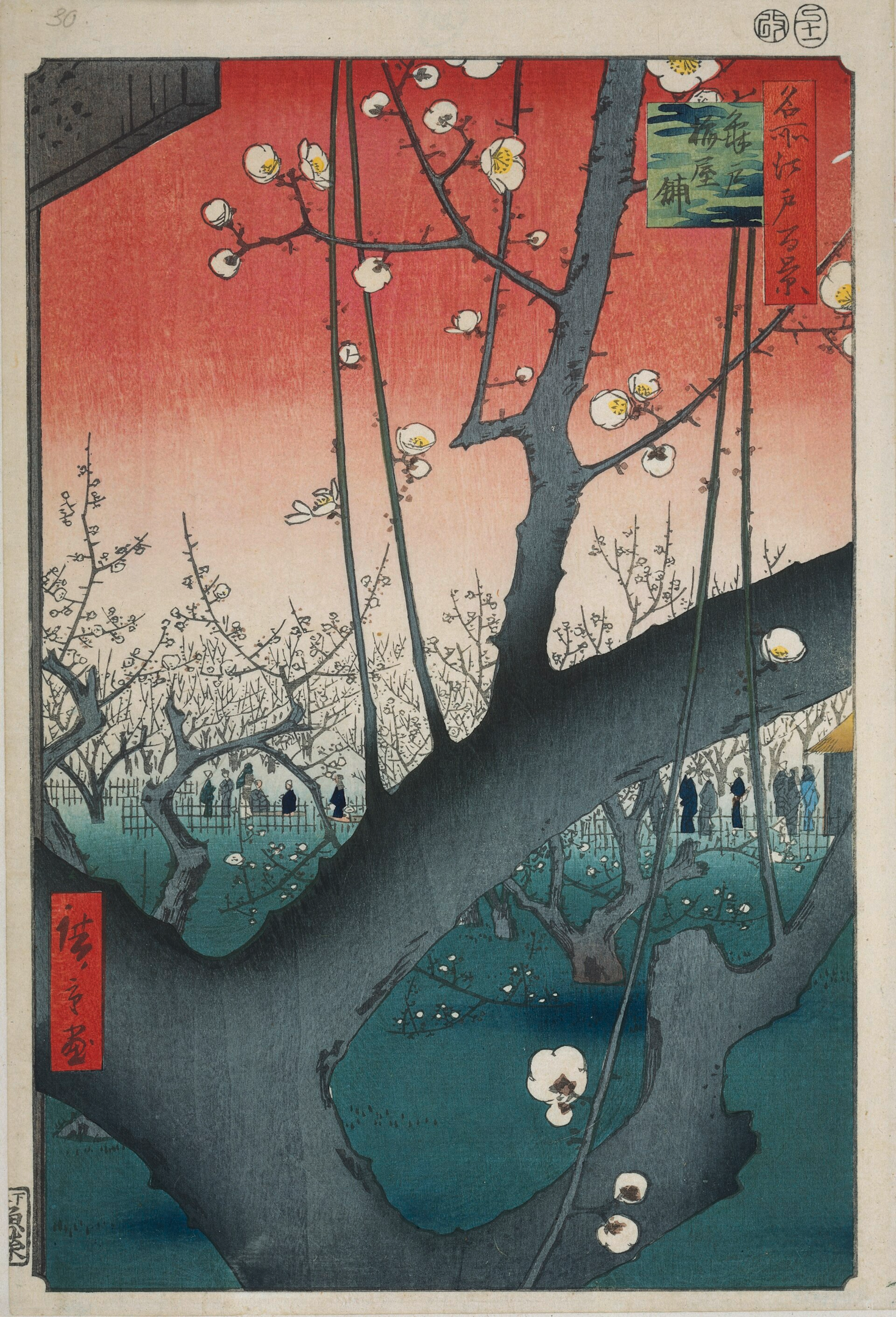

During the Edo period (1603-1868), ukiyo-e experienced its Golden Age, marked by a flourishing of artistic creativity and cultural innovation. Artists during this period produced a vast array of woodblock prints that captured the essence of daily life, entertainment, and the natural world. Kitagawa Utamaro, Katsushika Hokusai, Utagawa Hiroshige, and other artists emerged as masters of the medium, each contributing unique perspectives and styles to the ukiyo-e genre.

These artists depicted a wide range of themes in their art prints, including many a kabuki actor, courtesans, landscapes, and scenes of urban and rural life, reflecting the diverse interests and tastes of Edo society. The popularity of ukiyo-e prints soared during this time, with demand fueled by a growing urban middle class eager to acquire images of their favorite actors, beauties, and scenic vistas.

Alongside the artistic achievements of ukiyo-e masters, the Edo period also witnessed significant technological advancements and innovations in woodblock printing techniques. Printmakers developed new methods for carving and printing, resulting in sharper lines, richer colors, and greater detail in the finished prints.

Beyond the traditional cherry wood block and black ink, artists experimented with different types of paper, pigments, and printing tools, pushing the boundaries of what was possible within the medium. These advancements not only elevated the quality of ukiyo-e prints but also paved the way for the widespread dissemination of images and ideas throughout Japanese society.

The Emergence of Moku Hanga

“Moku Hanga” is a traditional Japanese woodblock printing technique that emerged during the Edo period and is closely related to ukiyo-e. The term translates to “woodblock print” in Japanese, distinguishing it from other forms of printmaking. This approach shares many similarities with ukiyo-e in terms of materials, tools, and methods, but it also incorporates some distinct characteristics and innovations.

One of the key differences between this printing style and earlier forms of woodblock printing is the use of water-based inks instead of oil-based inks. This allows for a wider range of colors and tones, as well as a more environmentally friendly printing process. Additionally, these prints often exhibit a softer and more delicate aesthetic compared to the bold and vibrant colors typical of ukiyo-e.

Despite these differences, moku hanga is deeply rooted in the tradition of ukiyo-e and draws upon many of the same techniques and principles. Artists who practice this form of Japanese print making often reference the iconic imagery and themes of ukiyo-e, such as landscapes, portraits, and scenes of everyday life. They may also adopt similar carving and printing techniques, including the use of multiple woodblocks to create layered and complex compositions.

Artistic Techniques and Process of Traditional Japanese Woodblock Printing

The woodblock printing process is a meticulous craft that involves several distinct roles and techniques. At its core are the artist, carver, and printer, each contributing essential skills to the creation of a woodblock print. The artist first designs the image, often drawing inspiration from sketches or paintings.

Once the design is finalized, the carver meticulously transfers the image onto separate wooden blocks, carving away the negative space to leave raised areas that will hold ink. This carving process requires precision and expertise, as even a small mistake can significantly impact the final print. Once the blocks are carved, the printer applies ink to each block using brushes or rollers, carefully aligning the blocks to ensure proper registration and layering of colors.

The paper is then pressed onto the inked blocks using a hand-held baren or a printing press, transferring the image onto the paper. This collaborative process of carving and printing culminates in the creation of a woodblock print, with each print retaining the unique character and craftsmanship of its creators.

Color and Composition

According to this resource from the Victoria & Albert Museum, “The earliest woodblock prints were simple black and white prints taken from a single block…Sometimes they were coloured by hand, but this process was expensive.” In the mid 18th century, “Additional woodblocks were used to print the colours pink and green, but it wasn’t until 1765 that the technique of using multiple colour woodblocks was perfected.”

Beyond color, composition and design are also crucial aspects of woodblock prints, influencing the overall aesthetic and storytelling of the image. Artists carefully consider elements such as balance, symmetry, and perspective when composing their prints, creating visually compelling compositions that draw the viewer’s eye and evoke a sense of narrative or emotion.

Whether depicting a serene landscape with Mount Fuji in the background or a dynamic kabuki scene, the composition of a woodblock print plays a central role in conveying the artist’s intent and engaging the viewer’s imagination.

Themes and Subjects in Classical Ukiyo-e

Landscapes and Nature

Within ukiyo-e, landscapes and nature are depicted with a profound appreciation for the beauty and tranquility of the natural world. Artists capture scenes of serene mountains, tranquil rivers, and lush forests, often imbuing them with a sense of seasonal change and the ephemeral beauty of passing moments.

Influenced by traditional Japanese aesthetics like wabi-sabi, which emphasizes impermanence and imperfection, ukiyo-e landscapes often evoke a sense of quiet contemplation and harmony with nature, inviting viewers to pause and reflect on the fleeting beauty of the world around them.

Kabuki Actors and Courtesans

Kabuki actors and courtesans are recurring subjects in ukiyo-e prints, reflecting the fascination with theater and the pleasure quarters in Edo-period Japan. Artists capture the theatrical and glamorous aspects of kabuki performances, depicting actors in elaborate costumes and striking poses that convey the drama and emotion of their roles.

Similarly, courtesans are portrayed with elegance and allure, their elaborate hairstyles and luxurious attire symbolizing the opulence and sophistication of the pleasure quarters. Through these single sheets, viewers are transported into the vibrant world of Edo society, where entertainment and beauty intersect in dazzling displays of artistry and performance.

Everyday Life and Urban Scenes

Ukiyo-e prints offer a vivid snapshot of daily life in Edo-period Japan, depicting bustling streets, lively markets, and leisure activities with remarkable detail and authenticity. Artists capture the rhythm and energy of urban life, portraying scenes of merchants haggling over goods, families enjoying picnics in the park, and travelers navigating crowded thoroughfares.

These single sheet prints provide a glimpse into the social dynamics and cultural customs of Edo society, showcasing the diversity and vibrancy of everyday experiences in Japan’s bustling capital. Through their depictions of popular scenes, ukiyo-e artists invite viewers to explore the multifaceted tapestry of life in Edo-period Japan, from the mundane to the extraordinary, with curiosity and fascination.

Ukiyo-e in the 19th Century

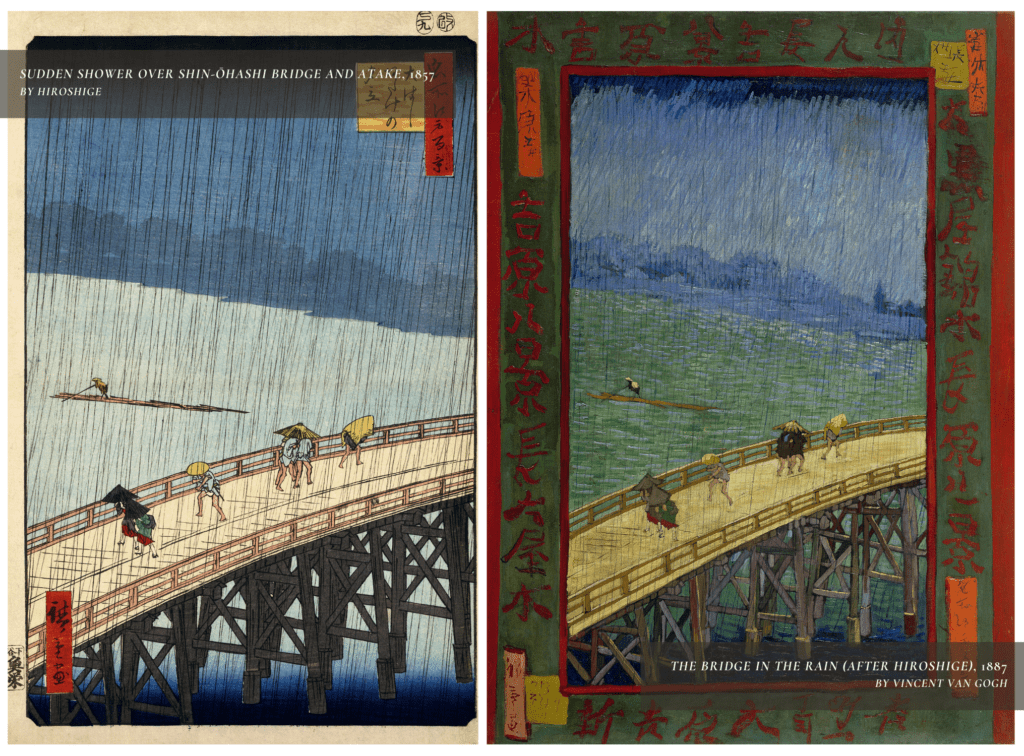

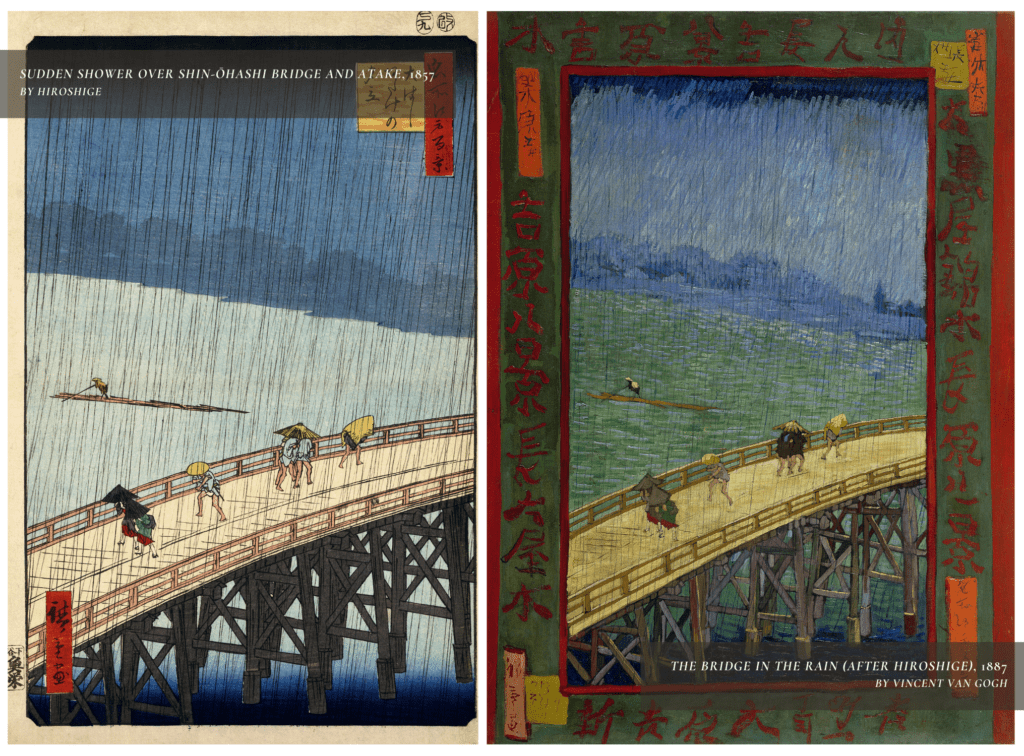

The introduction of ukiyo-e prints to the West in the 19th century had a profound impact on Western art and culture, particularly among European artists like Vincent van Gogh and Claude Monet. Ukiyo-e prints, with their bold compositions, vibrant colors, and innovative perspectives, captivated Western artists who were seeking new artistic inspirations and techniques.

Van Gogh, for example, was deeply influenced by Japanese woodblock prints, adopting elements of their style and composition in his own paintings. Similarly, Monet’s fascination with Japanese art is evident in his series of paintings depicting water lilies and Japanese bridges, which bear a striking resemblance to ukiyo-e prints. Through their reinterpretations of Japanese motifs and aesthetics, these artists helped to popularize the ukiyo-e style in the West and pave the way for greater cultural exchange between East and West.

Fuel your creative fire & be a part of a supportive community that values how you love to live.

subscribe to our newsletter

Japanese Woodblock Printing Today: Exploring Modern Interpretations of Ukiyo-e

There are contemporary Japanese artists who continue to iterate on the traditional Japanese woodblock print—carrying forward the legacy of ukiyo-e while also incorporating modern themes, techniques, and aesthetics. These contemporary artists demonstrate the continued relevance and versatility of woodblock printing in modern Japanese art.

Through their innovative approaches and reinterpretations of traditional techniques, they contribute to the ongoing evolution of the medium while preserving its cultural heritage. Below are a few notable contemporary Japanese artists known for their work in woodblock printmaking.

Takashi Murakami

While primarily known for his contemporary pop art and collaborations with brands like Louis Vuitton, Takashi Murakami has also experimented with traditional Japanese printmaking techniques, including woodblock printing. His works often blend elements of traditional Japanese art with contemporary popular culture, creating vibrant and dynamic compositions.

Masumi Ishikawa

Masumi Ishikawa is a renowned woodblock print artist based in Tokyo. He specializes in creating intricate woodblock prints that depict scenes of urban life in Japan, capturing the energy and atmosphere of city streets and neighborhoods. His prints often feature meticulous details and subtle color gradations, showcasing his mastery of the woodblock printing process.

Tomoko Murakami

Tomoko Murakami is known for her contemporary interpretations of ukiyo-e themes using woodblock printing techniques. Her prints combine traditional Japanese motifs with modern elements, resulting in visually striking compositions that bridge the gap between past and present. She often explores themes of nature, mythology, and the human experience in her work.

Yoshisuke Funasaka

Yoshisuke Funasaka is a woodblock print artist who specializes in poppy scenes using traditional Japanese printmaking techniques. His prints are characterized by their meticulous attention to detail and delicate use of color, capturing the beauty and tranquility of the natural world.

Final Thoughts: A Collector’s Perspective on Japanese Woodblock Prints

Collecting Japanese woodblock prints can be incredibly rewarding as it affords enthusiasts the opportunity to delve into the rich history and artistic mastery of ukiyo-e. However, navigating the world of ukiyo-e prints requires some understanding of the nuances involved. Identifying authentic prints and assessing their condition might involve a conservator, appraiser, or historian. Below are a few of our tips for those considering a woodblock collection.

Authenticity

Identifying authentic Japanese woodblock prints can be challenging, especially considering the prevalence of reproductions and forgeries. Look for key indicators of authenticity, such as the presence of an artist’s signature and seal, the quality of paper and ink used, and the overall condition of the print. Consulting reputable dealers, auction houses, or experts in the field can also help authenticate prints.

Editions and States

Japanese woodblock prints often went through multiple editions and states, each with variations in color, impression, and quality. Understanding the differences between editions (such as first editions versus later editions) and states (such as early versus late impressions) can provide valuable insight into the rarity and value of a print.

Pay attention to subtle changes in colors, bolder or finer lines, and any additional markings or inscriptions that may distinguish one edition or state from another.

Artist Signatures and Seals

Artist signatures (known as “gako” or “hanko”) and seals (known as “kao” or “goho”) are crucial for identifying the creator of a woodblock print. Familiarize yourself with the signatures and seals of prominent ukiyo-e artists, as well as the variations they used throughout their careers. Keep in mind that some prints may also feature publisher seals, censor seals, or other markings that provide clues about the print’s production and provenance.

Subject Matter and Style

Explore the diverse range of subjects and styles found in Japanese woodblock prints, from landscapes and nature scenes to portraits and genre scenes. Familiarize yourself with the distinctive characteristics of different artists and schools, such as the bold compositions of Katsushika Hokusai or the delicate beauty of Kitagawa Utamaro. Pay attention to the use of color, line, and composition to develop an appreciation for the artistic mastery behind each print.

Condition and Preservation

Assessing the condition of a Japanese woodblock print is essential for determining its value and longevity. Look for signs of damage, such as tears, creases, foxing, or fading, and consider factors like paper quality and conservation efforts. Work with a conservator if possible.

Proper storage and handling are crucial for preserving the integrity of woodblock prints, including protecting them from exposure to light, humidity, and fluctuations in temperature.

Design Dash

Join us in designing a life you love.

-

All About Our 7-Day Focus & Flex Challenge

Sign up before August 14th to join us for the Focus & Flex Challenge!

-

Unique Baby Names Inspired by Incredible Women from History

Inspired by historic queens, warriors, artists, and scientists, one of these unusual baby names might be right for your daughter!

-

Finding a New 9 to 5: How to Put Freelance Work on a Resume

From listing relevant skills to explaining your employment gap, here’s how to put freelance jobs on your resume.

-

What is Generation-Skipping, and How Might it Affect Sandwich Generation Parents?

The emotional pain and financial strain of generation skipping can be devastating for Sandwich Generation parents.

-

Four Material Libraries Dedicated to Sustainability, Preservation, and Education

From sustainable building materials (MaterialDriven) to rare pigments (Harvard), each materials library serves a specific purpose.

-

Do You Actually Need a Beauty Fridge for Your Skincare Products? (Yes and No.)

Let’s take a look at what dermatologists and formulators have to say about whether your makeup and skincare belong in a beauty fridge.